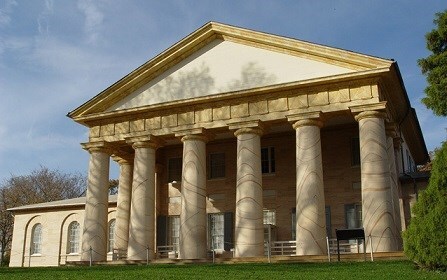

After seven years of planning and $12.5 million in restoration work, the National Park Service reopened Arlington House, the former home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee on Tuesday. The mansion — officially called the Robert E. Lee Memorial — was built by enslaved people more than 200 years ago. It sits high on a Virginia bluff overlooking the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington National Cemetery — and the graves of, among others, Union soldiers.

And just as NPS reopens the mansion to visitors, the community has been calling to tear it down. Or at least, the image of it.

Since 1983, Arlington House has served as the official logo of Arlington, its image adorning the county’s seal, flag, website, and stationery. It’s on police cars and government mail. Now, after a year of racial reckoning in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the county is in the process of redesigning its logo to remove the mansion’s image.

Julius Spain, president of the Arlington Branch of the NAACP, helped lead the effort to remove the representation of the home from official government materials. He says the memorial represents “a very dark time in our history.” He points to ongoing police violence against Black men and women.

“I’m not here to lift up Arlington House in any way, shape or form. It’s a slave labor camp where people were raped and killed, “ Spain says. “We have to preserve our past. Not glorify it.”

Nuanced preservation of the site and its complicated history was a big part of the goal of the restoration, according to NPS’s Charles Cuvelier, superintendent of George Washington Memorial Parkway.

“What we’ve tried to do is create windows into the past, even the ugly parts.” Cuvelier points to places in the restoration efforts — a portion of wall showing each layer of paint and plaster, revealing the underlying structure and how it’s changed over the years. The philosophy goes beyond plaster and paint; Cuvelier says they want to show how ideas and thinking have evolved as well.

But finding a way to memorialize the man who led the Confederate army and fought to protect the institution of slavery is not an easy task.

Beyond the main house and the adjacent quarters for enslaved people, there is now a space dedicated to exploring the complexity of Lee and his legacy. The small room includes descriptive panels that prod visitors to think deeply about the wisdom and culture of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, to parse the accolades Lee received, and also recognize the criticism.

Ida Jones, an historian and archivist at Morgan State University, studies African American history in the D.C. area, and says we need to witness all of our history.

It’s not going to be pretty, she says, “but Americans need to see and acknowledge what happened at Arlington House.”

“These national parks, these historic homes, these historic personalities need to be understood and viewed not as celebrity, but as filters through which we look at our past,” Jones says. “Arlington House honors Lee, but it also includes a nuanced conversation about Lee and the context in the times in which he lived and the decisions that drove his choices.”

Those choices are still part of the institutionalized racism that communities continue to grapple with. Some of the original housing for enslaved people, for example, once served as a gift shop, and much of the information about those who lived there has been lost because no one cared to preserve or remember it.

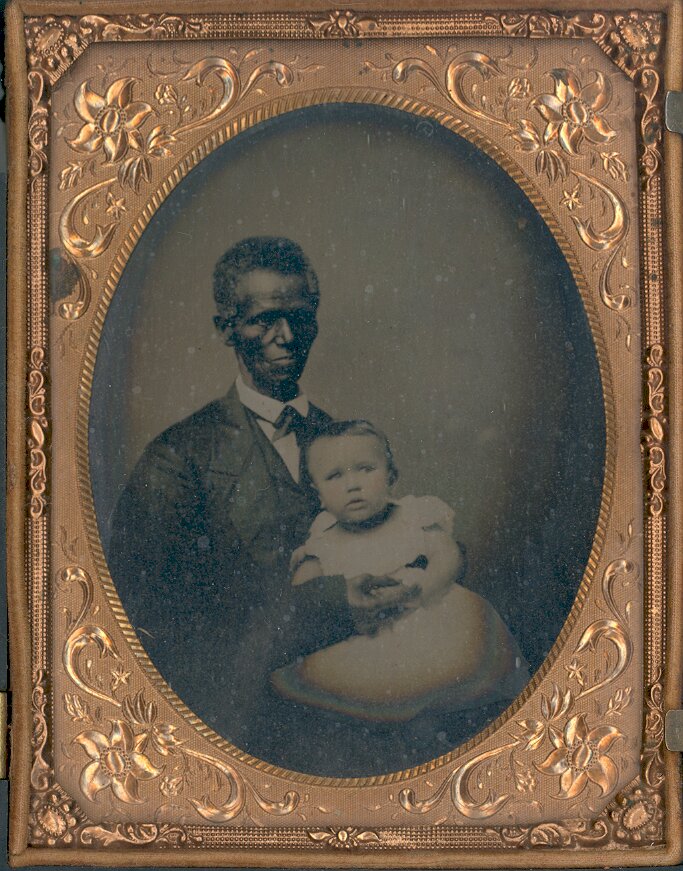

Archivists were able to trace the histories of some of the enslaved inhabitants, and their names are written on plastic sheets preserving the walls. Some people are known only by the work they performed, such as “Gardener,” or by their relation to another slave, like “Mary’s Child.” Many names have been lost forever.

During this renovation, NPS worked to uncover and restore as much information as possible about those enslaved at the site. But despite those efforts, it’s impossible to overlook the stark contrast with the main house, where Lee’s accounts and possessions were meticulously preserved over the more than 150 years since his death.

Prior to the Civil War, Charles Syphax was an enslaved resident in one of the cramped living areas. He oversaw the dining room at Arlington House. Syphax married Maria Carter, an enslaved woman whose mother was raped by George Washington Parke Custis, the original owner of the home and the step-grandson of George Washington. Charles and Maria were married in the mansion’s parlor, in the same spot where Maria’s half-sister, Mary Anna Custis, would marry Robert E. Lee a decade later.

Stephen Hammond is Charles Syphax’s great-great-great nephew and a family historian. When it comes to the complexities of the memorial, he says there’s a lot to process.

But he thinks the memorial is reopening at the right time. “This is an incredibly important time in the history of our country. We are evaluating the long-term legacies of that time and this house.”

He believes the restored mansion is now a place where people can have those more challenging conversations.

“We recognize that in this particular space, there are going to be people who disagree with how this new presentation of history is being told,” Hammond says. “And so we need to recognize that it’s about the whole history.”

Despite the focus on adding nuance and complexity to the history visitors see at Arlington House, the site remains an official memorial to Robert E. Lee. The Confederal general remains a controversial figure in the national conversation about preserving history, lionized by many white supremacists, and his legacy weaponized against communities of color.

That’s a task Julius Spain, Charles Cuvelier, Ida Jones, and Stephen Hammond all seem to agree should be at the heart of the next steps for the property.