Karen Hughes has a map of Fauquier County’s Black history in her head.

As she drives around the mostly rural Virginia county where she grew up, she offers a tour of that history, the result of diligent research, lived experience, and curiosity. She points to the sites of one-room segregated schoolhouses, creeks where Black churchgoers were baptized, corner stores where she ate ice cream, roads where Black family homes clustered together, the plantations where white people kept Black people in human bondage, and the places she avoided when driving home from work out of fear of the Ku Klux Klan. She’s captivated by the stories of the landscape where her family has lived for at least eight generations.

“From the beginning [of] my driving around, I would envision people running away, escaping. Any wooded areas and anything — I just was caught up in history,” she says. “As I would learn different things, I’d be thinking about, OK, what happened here? Who lived here?”

Hughes is the founding director of the Fauquier County Afro-American Historical Association. She started researching local history in the late 1980s, desperate to help her daughter see her Black ancestors in the history she was learning at school.

“I knew that if I put her in a Christian school, nine times out of ten, her identity would be non-existent from history,” Hughes says. “So I knew I needed to supplement that.”

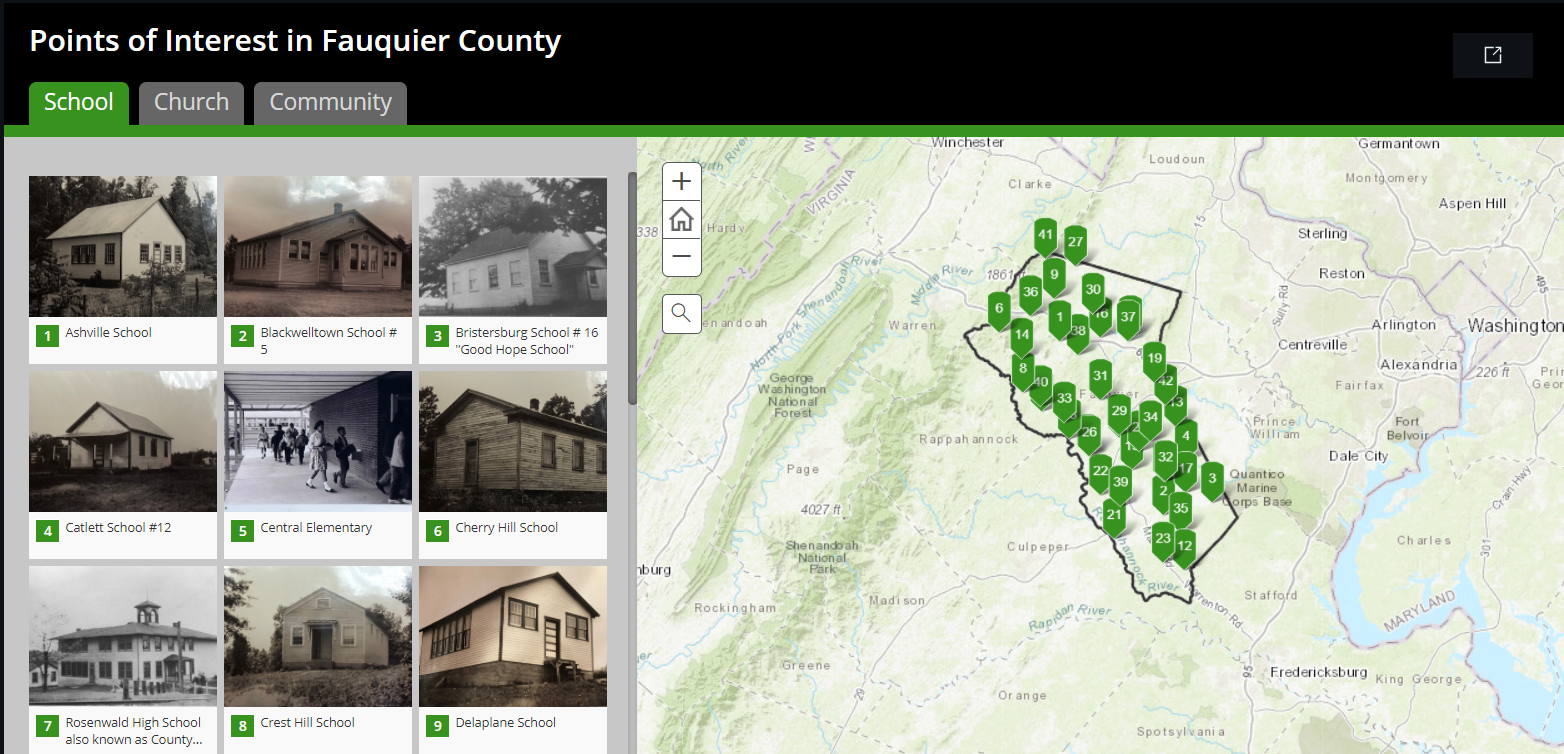

This summer, Hughes and her team — which includes her granddaughter, her sister, and a number of cousins — published the result of her passion for history: an interactive map of more than 140 sites of Black schools, churches, and communities in Fauquier County, with information on the Black families who lived here.

The map is a window into the rhythms of once-thriving Black communities in the county. Those communities dwindled as people escaped Jim Crow and pursued educational and employment opportunities outside of rural Virginia. A century and a half ago, Fauquier County was majority Black. Now, Black people make up just 8% of the population.

Hughes is working quickly to preserve the memories, family stories, paper records and even physical places from before and during that demographic shift. The historical association works with residents to collect long-forgotten documents from basements and attics. They seek out sales records and estate documents from families who enslaved Black people. And they conduct oral histories with older Black residents.

“We know that if we don’t preserve it, it will be lost,” Hughes says.

‘Everybody knew everybody’

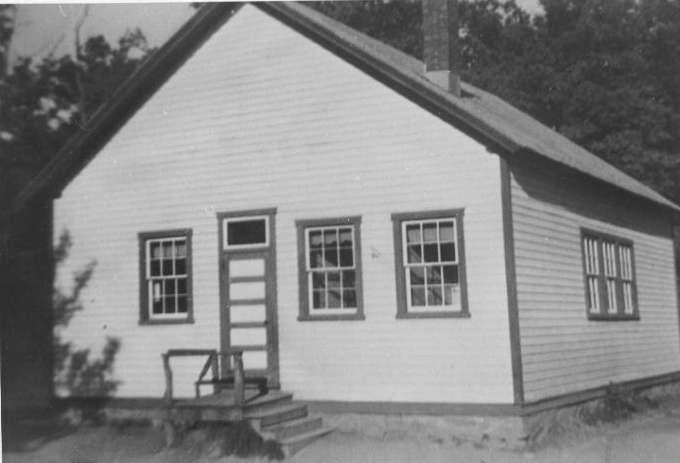

Hughes drives along a twisting wooded road — she remembers hearing her grandfather honk his car horn going around the bends — and pulls into a grassy lot that backs up to deep green woods. At the other side of the lot is a one-room schoolhouse, painted white, with a copper-colored roof.

This is one of the sites on the Black history map: it’s the Ashville School, built in 1876 and rebuilt in 1920 after a fire. Across the road is First Ashville Baptist Church, which was organized in 1874. Hughes’ grandparents lived nearby, and as she pulls in, she sees Reverend Phil Lewis. Lewis, 73, grew up attending both the church and the school in the 1950s. He recalls the details clearly: going to school early in the morning to start the fire before the other kids arrived, playing baseball at recess (he can show you exactly where the bases were), the way boys and girls had to take turns going to the outhouse, and how all the adults in the surrounding community looked out for him — and would call his parents to tell them where he was.

Lewis says he now recognizes the struggle and sacrifice that went into creating a sense of safety here in the 1950s, amid deep segregation, severe lack of community resources, and racist hate.

“After you grew up and you get back and you’re able to look back at this situation and look back at what is and what transpired — that was a lot of challenges that that they went through in order for us to do things like just go to school,” he says.

“I’m glad to be from a community like this, I really am,” says Doris B. Fletcher, 79, who also attended the Ashville church and school. “I think it enriched our thinking ability towards another person. And that’s good.”

Many other sites on Hughes’ map mirror the Ashville arrangement: a community church and a school close together, with the school founded and supported by the church congregation. Black students attended mostly one-room school houses in the county until 1964, when the county created modern “consolidated” schools. These schools were still segregated — Fauquier County resisted integration until 1969, 15 years after Brown v. Board of Education — and the county bussed Black children long distances to class.

Today, the church is still operating and the school sits empty. There are many fewer Black people in the neighboring community and more new houses where white families have moved in. Lewis recalls going door to door as an adult, inviting the newcomers to come to the Ashville church.

“We went up in that new little section, man, and I didn’t know nobody,” he recalls. “We went down and the guy come out on the porch, out in the front yard. And I waved at him, you know, to say ‘hi.’ They hollered back at me, ‘Your mama.’”

‘This is where we come home to’

Another site on the map is Mt. Olive Baptist Church, a bright white building from the early 1900s that looks out over sprawling green fields. Inside, afternoon light slants through stained glass windows, and old photos of churchgoers gone by are kept safe in a glass case in the fellowship hall. Here, Hughes meets Erma Grant Robinson and her cousin Earsaline Anderson.

“This is all I know,” says Robinson, 65, whose grandparents were founding members of the church. “I was baptized here when I was six years old, so I don’t know anything else but Mount Olive … It has been very much a growing spot for me.”

Robinson and Anderson, 76, remember a congregation engaged with the world — different Baptist organizations, missionary efforts, and visiting ministers from all over the world. They also remember the church’s big homecoming celebrations, when relatives who had moved away would return to Fauquier County to worship in their family’s church.

“It was just such a happy occasion to be able to share your roots with them and let them know, ‘Hey, this is where we grew up, and this is where we learned all about God, and this is where we come home to,’” Robinson recalls.

After the homecoming service, the congregation would visit the homes of the church’s local families for food and fellowship. Different churches across the county would host their homecomings on different weekends, to allow people to attend several different events.

“Homecoming [started in] June until the last Sunday in September,” Anderson says. “No church would take an engagement in the afternoon because you would visit your neighboring church.”

Today, the pandemic has paused the homecoming tradition. And there are more permanent changes, too: the congregation at Mt. Olive has shrunk, and the members like Robinson and Anderson who can remember the old celebrations are dwindling. Most people in the pews on Sundays before the pandemic were over 60, and many came from outside Fauquier County. Anyone coming back to Mt. Olive now will drive along a road where many white families have moved in.

“Atoka Road was all Black. And now you look at it, you may have four homes on this road,” Anderson says. “So that’s telling you right now we’re not going back to normal.”

‘You understand it’

The work of documenting Black history — of holding the joy and resilience of Black families and communities alongside the brutality of racist experiences — takes its toll.

“You go through anger, disbelief or frustration, acceptance. And you try to understand,” Hughes says. “It may not set well with you, but you understand it.”

Hughes isn’t the only one with complicated feelings about her home and its history. Granddaughter Aysha Davis, who moved back to Fauquier County with her 18-month-old daughter during the pandemic to be with family and to help with the technical parts of the mapping project, remembers an incident from 2007 very clearly.

“We came home and there were Klan recruitment fliers being on the doors of the neighborhood,” she says. “That moment that was like, where am I?”

Davis says part of her motivation in joining the mapping project was a desire to see her ancestral home confront its ugliest history.

While the Afro-American Historical Association project is about the past, it may also shed light on how the county’s racial history shapes the present-day landscape, including which places have received historic designations, where services like internet and other basic utilities reach, and how the county might move forward with planning for development in the future.

“Why are the former dumping sites in the Black communities?” Hughes asks. “And why and when does the internet stop? I’d like to talk about that.”

“That lack of infrastructure is not just limited to broadband. It’s also water and sewer. It’s also public transportation,” says Kirsten Hammer Dueck, a senior program officer with the PATH Foundation, which is providing funding for Hughes’ project. “The further and further you get from the center of the county, the lighter and lighter those resources are.”

Understanding the historical distribution of resources and infrastructure is a key step if the county is to begin to solve those problems, Dueck believes.

“As we look at what the county’s plans are for expanding service, for improving infrastructure, understanding where it was laid and why and when is going to be of essential importance for understanding how to do better and how to move forward,” Dueck says.

Historical knowledge lends context to some more positive aspects of the county’s present and future, too. Dueck points to the Haiti neighborhood in Warrenton, the county seat, which was founded as a thriving community of free Black people, became a regional hub of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and is now experimenting with a new way of seeking justice — exploring options for mixed affordable housing.

And while it’s already having an impact on current issues, the mapping project itself is far from finished. Hughes wants to add more layers: information about Black cemeteries and sites of Virginia’s history of enslavement, like quarters and auction blocks. She hopes including those sites on the map will help more people see the threads of community anguish and community resilience woven into the landscape.

“It gives a true understanding of Fauquier’s foundation, because for so long it was portrayed as a different history, as though Blacks were here, but they weren’t here,” she says. “Fauquier becomes richer when you have the more complete story.”

Margaret Barthel

Margaret Barthel