This weekend’s March On For Washington and Voting Rights and the Make Good Trouble Rally are expected to bring thousands to the National Mall to demand expanded access to the vote. The march comes amid a wave of legislation in majority-Republican state legislatures that seeks to make voting more difficult. But in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, the story has been the exact opposite: legislators have actually passed significant expansions to voting rights — particularly for currently and formerly incarcerated people — this year.

There is, of course, one glaring example of local disenfranchisement: D.C. is not a state, which means that its residents do not have a voting representative in Congress. But local elections in D.C. have gotten more accessible, as the city recently expanded absentee voting and granted residents who are currently serving felony sentences their voting rights.

Lawmakers in Virginia passed a historic voting rights bill this year and initiated a process that could ultimately restore the right to vote for 400,000 people who had previously been convicted of felonies. And in Maryland, new laws have expanded voting access for currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, expanded early voting, and made it easier for people to vote by mail.

“Hearing from other state chapters … and what they’re experiencing, and all the news coming out of Texas — I just cannot imagine having to navigate that landscape,” says Joanne Antoine, the executive director of Common Cause Maryland, a non-partisan group that advocates for open government and expanded access to the Democratic process.

Unlike other states, where her peers are playing defense against attempts they say will shrink the electorate, Antoine says she feels like she and other advocates in Maryland came out of this year’s legislative session with “so many victories.”

Ahead of upcoming elections, advocates say they’ll be looking to see how these new laws are implemented in practice — and looking to build on recent victories in expanding access to the vote.

This weekend’s marches come on the 58th anniversary of the March on Washington. There are two headlining events: the March on for Washington and Voting Rights by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Make Good Trouble Rally by the Lincoln Memorial. Organizers of both events wrote in their permit requests that they expect as many as 150,000 attendees combined.

Much of the focus will be on Democrat-led efforts to strengthen access to the vote nationwide, including Congressional legislation that supporters say will make it harder for individual states to restrict access to the ballot.

One of those measures, named after the late Georgia congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis, passed in the House but faces strong Republican opposition in the Senate. Another bill, the For the People Act, seeks to curb gerrymandering, expand early and mail-in voting, and reform campaign financing. Because of Senate filibuster rules, Republicans have the votes to block this effort too — which is one reason why activists this weekend are pushing for senators to change the rules and get rid of the filibuster altogether.

While the march is focused on national legislation, there’s one local cause that is playing out on that stage: the fight for D.C. statehood.

It has seen historic gains in recent years, including the passage of a statehood bill in the House of Representatives. Still, the legislation remains firmly stuck in the Senate, hampered by a filibuster and even facing skepticism from some moderate Democrats like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia).

Jamal Holtz, the lead organizer for the advocacy group 51 for 51, says it’s important to get the statehood message before the crowds on Saturday.

“After everyone went home after the March on Washington in 1963, the residents of Washington, D.C. were left behind without any congressional representation,” says Holtz. “So when we’re talking about the sweeping … voter suppression … happening across the country, you have to include the voter suppression that’s also happening right here in the District of Columbia, in the nation’s capital, at the heart of our democracy, where there are several hundred thousand people who are American citizens and tax-paying citizens who do not have a vote in their democracy.”

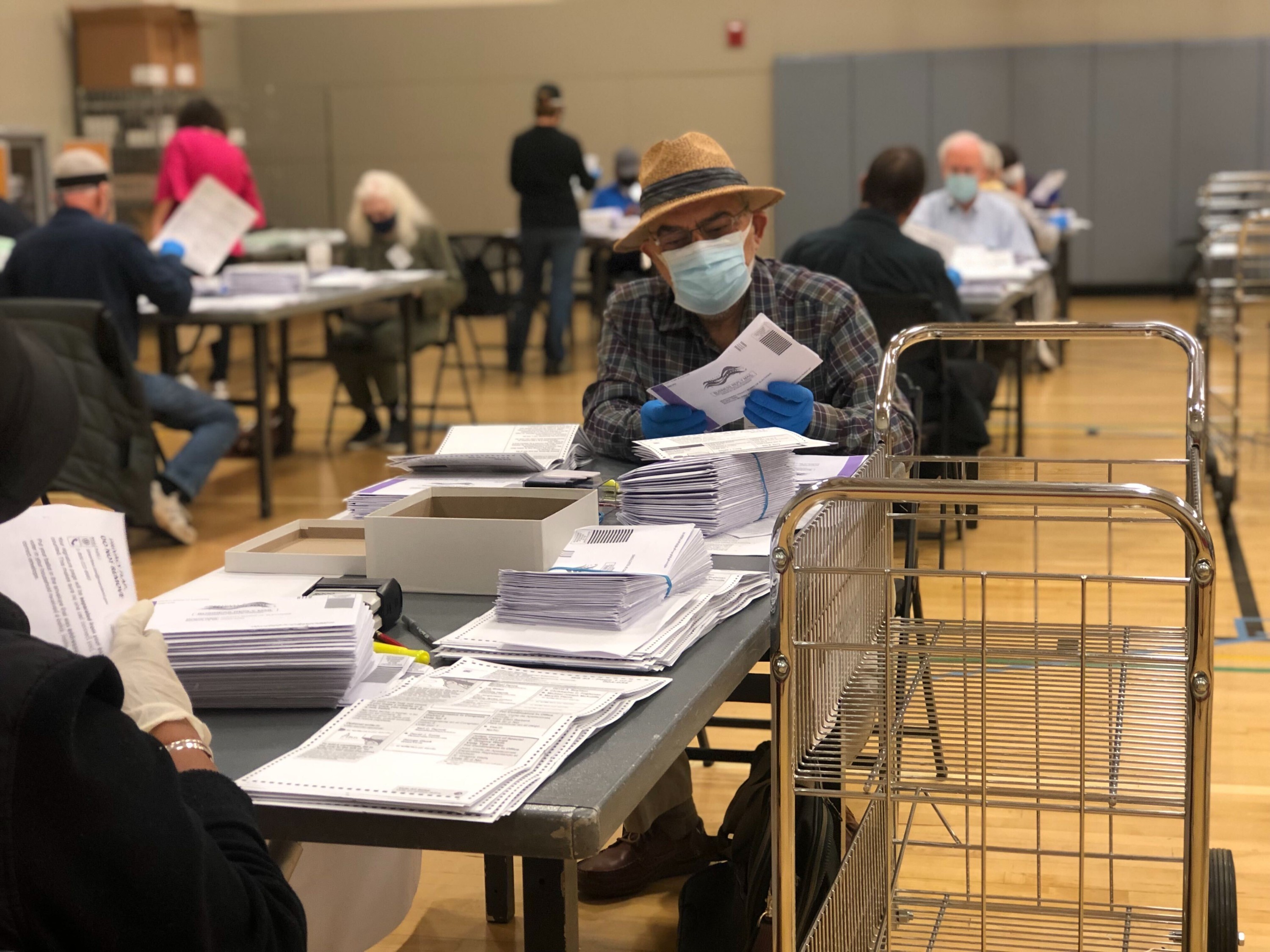

Meanwhile, D.C. has been at the forefront of efforts to expand the franchise and make voting easier. The city sent all registered voters a ballot in the mail ahead of the 2020 general election— and election officials are considering doing so again in future election cycles. The city has same-day and automatic voter registration, 16-year-olds are allowed to pre-register to vote, extensive early voting options are made available, and candidates running for office can use a new public financing program to fund their campaigns.

Even more changes could be coming: D.C. lawmakers are expected to debate bills in the coming year that would allow non-citizen permanent residents to vote in local elections and move toward a ranked-choice voting system like the one recently used in New York City’s mayoral election.

D.C. also took a significant step in 2020 when it allowed residents serving felony sentences to cast ballots from prison, joining Maine, Vermont, and Puerto Rico as the only states where it currently takes place.

“D.C. definitely joined an elite group of jurisdictions that have done away with or never even had felony disenfranchisement to begin with,” says Blaine Bowie, an attorney at the Campaign Legal Center.

Implementing the measure hasn’t been without its challenges, the biggest being that most D.C. residents serving felony sentences are in federal custody, often held at prisons hundreds or thousands of miles from the city. During the coronavirus pandemic, many facilities also enforced lockdowns that even further restricted communication with the world outside.

Last September, the D.C. Board of Elections sent voter registration forms to 2,400 D.C. residents incarcerated at more than 100 federal facilities across the country. According to the board, just under a quarter of those residents registered to vote — and about half of those who registered actually cast ballots.

Another 512 were registered and 333 voted at the D.C. Jail, which holds people awaiting trial, serving misdemeanor sentences, and some incarcerated felons.

This also resulted in a particularly novel development — a D.C. resident serving out a felony sentence at the D.C. Jail was elected to serve on a neighborhood commission earlier this year, which voting rights advocates say may be a first nationwide.

The proposed For The People Act wouldn’t go as far; a push to include a provision doing away with felony disenfranchisement in prison failed in the House this spring. Still, the measure would more broadly allow people who serve out their sentences for felony offenses to regain their voting rights, and advocates see that cause picking up steam.

“What we’re really talking about is expansion of the franchise, the inclusion of more populations, and then the efforts to push back on [laws] have come in waves during the Jim Crow era and during the expansion of the criminal legal system in the 70s,” says Bowie. “It is about pushing back on racist laws, which these are. And we can’t really have an inclusive democracy as long as we still have these Jim Crow anti-voting laws on the books.”

Enabled by Democratic control of the state legislature, Virginia became the first Southern state to enact its own version of the Voting Rights Act this year.

“What you see in many other places in the South is that there’s this effort to suppress the vote and Virginia, by contrast, took a step in the opposite positive direction,” says Mary Bauer, Executive Director of the ACLU of Virginia.

Or, as the New York Times put it in a headline: “Virginia, the old Confederacy’s heart, becomes a voting rights bastion.”

Governor Ralph Northam has also used his discretion as governor to restore voting rights to about 70,000 people with felony convictions upon the completion of their sentence.

Still, “the fight is not over,” Bauer says, because automatically restoring the vote to all Virginians who have been convicted of felonies — an estimated 400,000 people, a majority of whom are Black — will require an amendment to the state’s constitution.

“Virginia’s history has been so deeply committed to the idea of disenfranchising its Black citizens that it enshrined this in the 1902 Constitution,” says Bauer.

The legislature still has to pass the amendment once more before it moves to a state-wide ballot referendum. Bauer says the polling she has seen makes her confident that if it moves to the referendum stage, most Virginia voters will support it.

But, unlike in D.C., these expansions of voting rights will not apply to people who are currently incarcerated for felony sentences. “We were deeply disappointed that those individuals were carved out of the bill,” says Bauer.

In Maryland, people currently serving time for felony convictions also are not eligible to vote. But people who have already served their time for felony convictions have long been eligible — as have people in jail pre-trial or serving sentences for misdemeanors.

The issue, advocates say, is that these voters have not actually had meaningful access to the ballot — which is why they pushed this year to expand outreach to those eligible voters.

Lawmakers ultimately passed bills that require the state’s corrections department to give people voter registration forms upon their release from prison — and require election officials to do more outreach to eligible voters within the state’s prisons and jails.

“It’s always been our partners, groups like Out for Justice, that have been going into the facilities and trying to assist with those efforts,” says Antoine. But now, “if those reforms are implemented correctly, [currently and formerly incarcerated people] will be informed of their right to vote and more importantly, have a meaningful process to go ahead and do so.”

Lawmakers in Maryland also passed several other voting-focused measures this year, including a permanent expansion of mail-in voting, increases to the number of early voting centers, and efforts to expand voter outreach to students and military service members.

But, advocacy groups still have other reforms on their mind. Antoine says she would like to see Maryland allow election boards to pre-process ballots earlier so they can more efficiently tally results, establish a better process for curing ballots, and improve tracking so that people can easily get confirmation that their ballots have been accepted.

Antoine also adds that she would have liked to see more drop-off boxes added to jails in the state. Lawmakers ultimately carved out a provision that would have required the state to place ballot drop-off boxes in jails across the state, so only one correctional facility — the Baltimore City central booking facility — will have a drop-off box for the next election. .

Organizers of this weekend’s rallies have been expressing a sense of frustration that decades after the civil rights movement, they are still pushing for many of the same things. Democratic Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama, who sponsored the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, recently said that “old battles have become new again.”

Locally, one old battle — D.C. statehood — will certainly take the spotlight. But apart from that, the work for many local advocates in the coming months will be about making sure that the legislative victories of the past year actually translate to improved access to the ballot.

“I think oversight right now is really the biggest concern for everyone,” says Antoine.

Jenny Gathright

Jenny Gathright Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle