Kathleen Donahue, owner of Capitol Hill game and puzzle shop Labyrinth, is hoping to get some return on her huge investment of time this holiday season.

“Every single week, for the last six months, I have been sending in massive orders, and I get filled maybe a tenth,” Donahue says in a small, crowded room at the back of her 10-year-old store. “And then I take that entire list and send it to the next person. And they might be able to fill a little bit more. And then I send it to somebody else and it just keeps going.”

The holiday-shopping frenzy is well underway, and retailers across the D.C. region and the nation are contending with shipment delays, higher prices and low inventory. Some 20 months into the pandemic, a host of challenges—including labor shortages, Covid-mitigation efforts at ports and factories, and rising demand for goods—have created supply-chain issues that plague countless industries, and aren’t likely to resolve themselves anytime soon.

Some holiday shoppers hoping to avoid these problems are turning away from big-box retailers and looking toward local stores. But national chains and online behemoths aren’t the only ones feeling the crunch; shops in D.C., Maryland and Virginia are struggling to replenish stock, keep prices down and, in some cases, find additional revenue streams.

For Labyrinth, November and December sales account for 30 to 40 percent of the shop’s annual revenue. Each summer, Donahue typically starts stocking up on end-of-the-year inventory, this year with games such as Tacocat Spelled Backwards and Unstable Unicorns. That’s what she did this year, but the ordering—due to low inventory—never seemed to end.

Some products, including those made with wood, cardboard or plastic, are very hard to find, she says. Others, such as the Christmas puzzles she’d usually have in stock this time of year, aren’t being shipped out at all. But with diligence, Donahue has been able to get her hands on enough inventory that she thinks Labyrinth can maintain well-stocked shelves throughout the season.

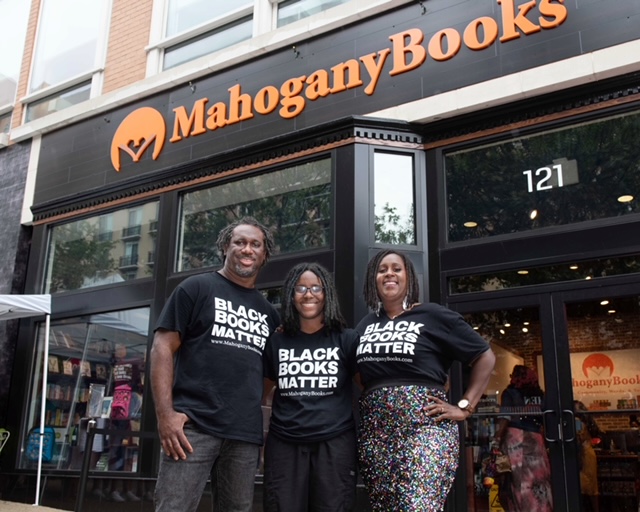

MahoganyBooks co-owners Ramunda and Derrick Young also ordered early to try and circumvent any supply shortages. Their bookstore—which launched virtually in 2007 and carries almost exclusively books that are by, for, or about individuals from the African diaspora—has two physical locations, in Anacostia and National Harbor. The holiday season, Ramunda says, is their biggest for sales.

“It is like the Super Bowl—this is it,” Ramunda says. “In preparation and thinking of the holiday, and getting warnings about shipping delays and merchandise being potentially out, we really planned far in advance.”

While MahoganyBooks hasn’t seen widespread price increases from their suppliers, Ramunda says, many retailers have watched wholesale prices climb, due to cost increases for raw materials and the transport of goods.

At Fredericksburg bath-and-body shop Sugar and Spruce, holiday sales ordinarily make up roughly a third of the store’s annual revenue. While staff members at the near-decade-old company make a large share of the brand’s products on site, the ingredients and packaging for all the candles, bath bombs and sugar scrubs can be hard to find—and expensive.

“Supplies like bags, tissue paper, gloves, etc. take a while to get to us, and we sometimes have to shop at local shops to supplement our inventory,” according to co-owner Morgan Wellman. “Containers and ingredients are frequently out of stock as well, and prices have skyrocketed so we have had to make a lot of changes to maintain our margins.”

A citric acid shortage, for example, has ratcheted up the shop’s per-bag cost of the common soap additive by some 300 percent, Wellman says. Those, and other soaring costs, have spurred Morgan, as well as her mother and shop co-owner Crystal Wellman, to make some changes on the customer side.

“We used to offer bulk pricing on a lot of our products but had to do away with those to keep up with rising costs,” Morgan says. “We have also raised the price on a few products to offset all these new costs, but we are doing our best not to pass on these rising costs to consumers.”

Prices are also on the rise at Arrow Bicycle, a Hyattsville cycling depot that opened in 2008 when neighbors and onetime co-workers Chris Militello and Chris Davidson decided to collaborate on their own shop. The fourth quarter is not their biggest for sales, an honor that typically goes to the spring and early summer, when sunnier days summon would-be cyclists. But after a few record months of sales at the pandemic’s onset, the shop hasn’t been able to “restock the pantry,” Militello says.

“We still have the demand; we just can’t fulfill the demand right now,” he says.

Arrow Bicycle’s inventory, nearly 100 percent of which is manufactured overseas, is down significantly. The shop has just 17 percent of the total bicycles it would normally carry this time of year. The nearly bare racks and shelves, Militello says, are also waiting to be lined with parts like bicycle chains and gear such as cycling shoes and helmets.

“[Inventory] was affected all the way through the supply chain,” Militello says.

As the shop waits for stock to be replenished, its owners have had to look elsewhere for revenue streams. Arrow Bicycle has leaned into existing contracts with local police departments to perform maintenance on their bike fleets, and stepped up its service component in other ways. The company has also begun advising nearby localities on where to install bicycle racks, and assists with those installations. But even with expanded service efforts, the shop is down some 30 to 40 percent in revenue.

Militello says his suppliers are projecting that Arrow Bicycle won’t likely see its stock replenished for another year. While his customers, and holiday shoppers around the region, wait for some of their favorite items to return, he urges them to stay close by.

“Just support your local retailers, whether it’s your local brewery, your local bike shop, local tattoo artists. Buy in your community because the tax dollars stay there. And those tax dollars give us new bike paths and streetlights and crosswalks,” Militello says. “Shop local.”

Eliza Tebo

Eliza Tebo