Electric vehicle enthusiasts and public transit aficionados: there is good news as 2021 draws to a close. Metro is buying its first ten battery-electric buses, and plans to operate them on routes throughout the region next year.

It’s the first step of Metro’s plan to transition to an all-zero-emission bus fleet by 2045. To start out the transition, Metro put out a request for proposals, looking to purchase ten standard-length 40-ft. buses from different manufacturers. The transit agency will test out the buses and chargers in real-world conditions, and asses their performance.

Separately, Metro also plans to buy two 60-ft accordion electric buses next year, a first in the region.

“Investing in a zero-emission bus fleet will contribute significant environmental and health benefits to the region by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving regional air quality,” said Paul Wiedefeld, Metro’s general manager, in a statement. Zero-emission buses, he said, will provide riders with “a clean, quiet, and more comfortable ride.”

But environmental groups, who have been lobbying the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority to go electric, say the agency is moving too slowly, and that a 2045 target is too far off, well behind numerous other cities.

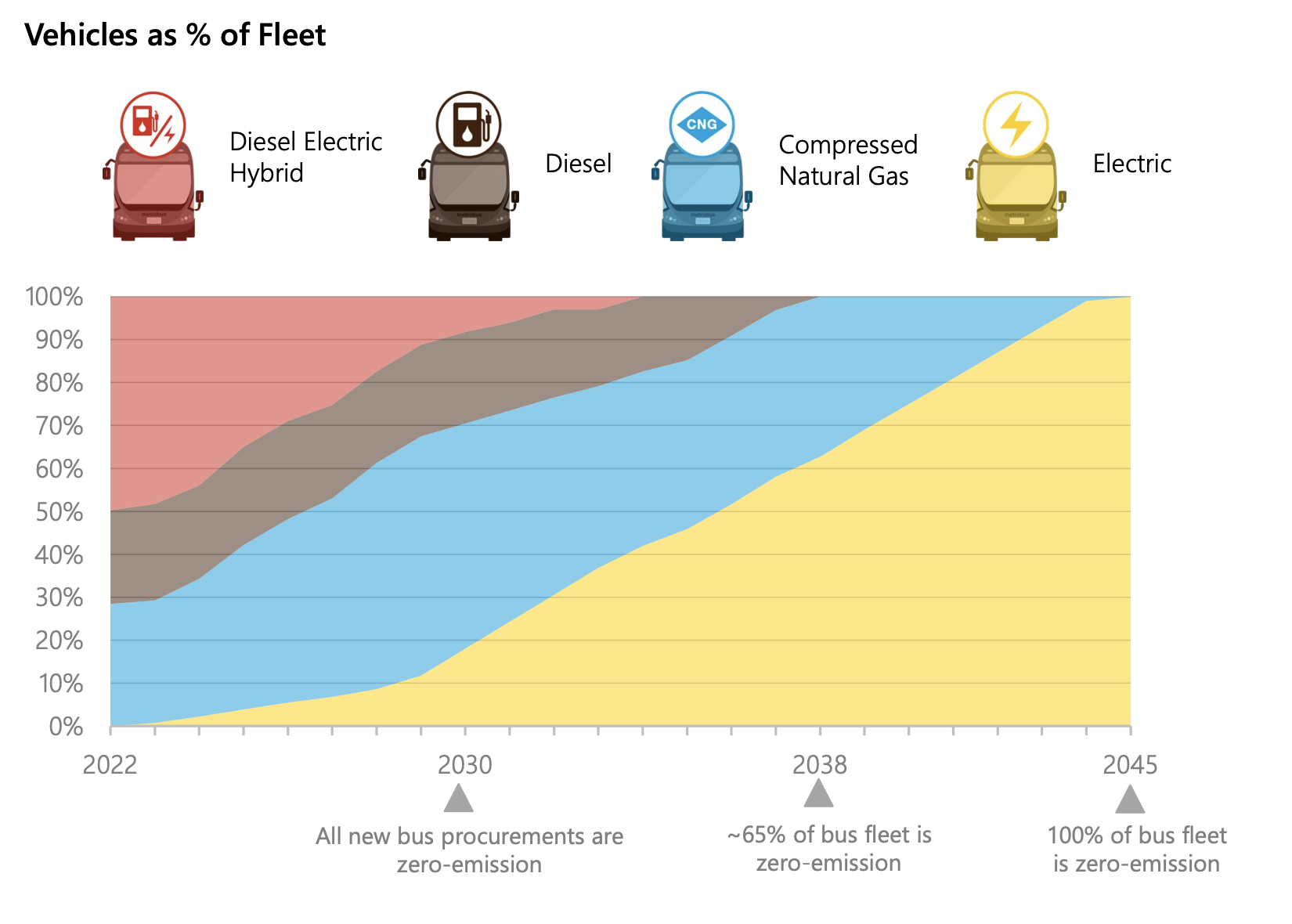

“Unfortunately WMATA’s current plan is for only 20% of the fleet to be electric by 2030,” says Lara Levison, with the D.C. Chapter of the Sierra Club. “They want to continue buying polluting diesel and compressed natural gas buses in the meantime, and we strongly oppose that.”

Levison points to Los Angeles, which plans to have a fully zero-emission fleet by 2030 — a decade and a half before WMATA. L.A. operates 2,300 buses, compared to WMATA’s 1,500, and has already converted an entire bus line to battery-electric.

New York City plans to transition its 5,800 buses to zero-emission vehicles by 2040. It already has two dozen electric buses criss-crossing the city, and plans to buy 500 more by 2024. Other cities with early timelines for bus electrification include San Francisco, Seattle, and Chicago.

Metro has also lagged behind other transit agencies in the D.C. region in terms of trying out electric buses. D.C.’s Circulator system owns 14 battery-electric buses, and Alexandria’s DASH and Montgomery County’s Ride On also have several. WMATA purchased one electric bus in 2017 but it has seen limited use.

Levison says not only is Metro getting “a little bit of a late start” in the transition to electric, but its plan also “backloads the electrification of the fleet” so most of the transition happens after 2030. This may make sense from a budgetary standpoint: electric buses are currently 45% more expensive to purchase at the outset than diesel buses, according to Metro. However, electric bus prices are expected to drop and be on par with diesel buses within a decade.

Electric buses are much cheaper to fuel up than conventional buses, and can save money over the lifetime of a bus. Metro estimates electric buses will reduce fuel costs by 40%. The new buses will bring higher maintenance costs in the short term, according to Metro, but 10% to 20% savings on maintenance in the long term.

Metro plans to buy only zero-emission buses starting in 2030, with a goal of 65% of the fleet running on electricity or other zero-emission technology by 2038. This will translate to a 56% reduction in emissions by 2030, and a 78% reduction by 2038.

Under D.C. law, 100% of electricity sold in the District must come from renewable sources by the year 2032, so any buses charged in D.C. would be running on clean energy.

Metro’s current bus fleet is 55% hybrid diesel-electric, 30% CNG, and 15% diesel. The newer hybrid and CNG buses emit 20% to 30% less greenhouse gas, compared to diesel buses.

Even before Metro’s transition to electric buses, taking transit is a green way to go: bus trips emit 25% less greenhouse gases than single-occupancy car trips per mile, while rail trips emit 65% less.

And Metro, in its defense, notes that it already operates the largest electric vehicle fleet in the region, in the form of its 1,200 Metrorail cars.

This story was updated to correct the spelling of Lara Levison’s name.

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston