Soapstone Valley, home to one of the most polluted tributaries in Rock Creek Park, is about to get a major sewer upgrade to keep the 100-year-old pipes from leaking into the stream. The upgrade has been in the works for years, and is the first of several major projects to shore up antiquated sewers on National Park lands in the District. But as the project is about to get started, neighbors are fighting it — concerned about the environmental and health impacts, including loss of trees and the toxic chemicals that will be used to repair pipes.

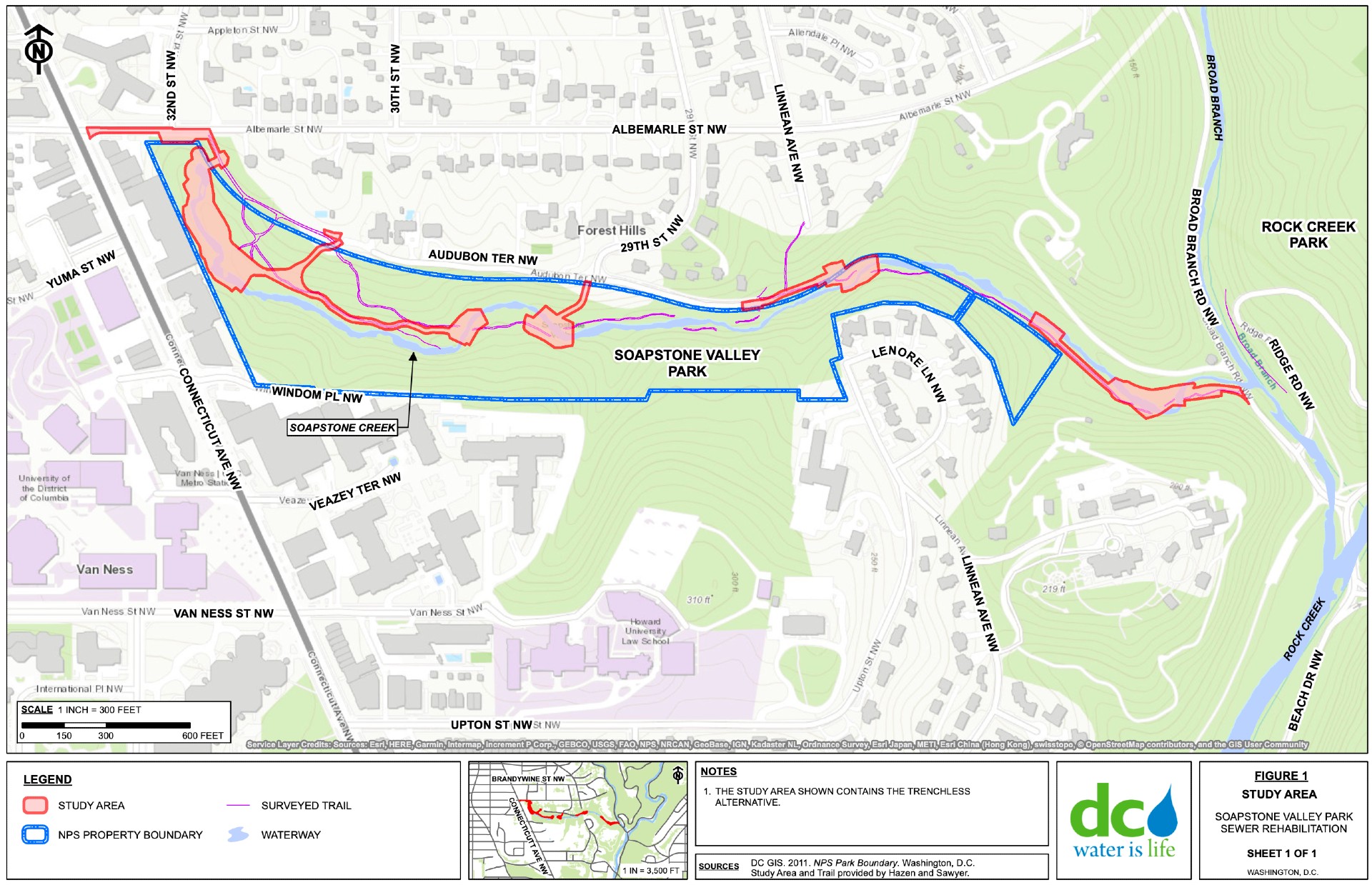

Soapstone Valley meanders from Connecticut Ave. in Upper Northwest D.C., down to Broad Branch, near its confluence with Rock Creek. The trail through the valley is dotted with rusted old manholes, marked with the word “sewer.” If you get close, you can hear — and smell — the sewage line running under the park.

“This is the epitome of why this project needs to be done,” says DC Water engineer William Elledge, approaching an exposed sewer pipe that spans the creek. “This was all buried when it was originally constructed.”

A century ago, the sewer pipe where Elledge stands crossed under the creek — now due to erosion, it’s above the creek, with creek water flowing under the pipe.

“What that’s a sign of is that the entire stretch is about to be completely undermined,” says Elledge.

DC Water plans to spend the next two years relining and repairing about 1 mile of the sewer pipes in Soapstone Valley, and restoring the creek. The project has been in the works for more than a decade, and is finally scheduled to get started in the next few weeks.

DC Water documented the damage to the aging sewers using closed-circuit television cameras to look inside the pipes. In every section of sewer examined — except for two that had been previously lined — the cameras showed cracks, fractures, holes, leaks or roots growing into the pipe. There are six places where vulnerable, exposed pipe crosses the creek, and 29 “defective” manholes in Soapstone Valley, according to an environmental assessment of the project prepared by DC Water and the National Park Service.

I got a tour of the site from Elledge and Eric Lienhard, an engineering consultant with Hazen and Sawyer, a firm hired by DC Water to work on the project.

“If you don’t mind getting your feet wet, let’s cross here,” says Lienhard, stepping onto the old pipe crossing the creek. He points upstream to an exposed manhole, rising some 10 ft. above the water — indicating where the surface level used to be, before erosion exposed the pipes.

“Just in the last decade, we’ve had a handful of failures and some of those have been leaks where that sewage has actually been getting into the stream,” says Elledge. “It’s only a matter of time before there’s an even more colossal failure.”

The $7.5 million project in Soapstone Valley is the first of several to refurbish old, deteriorating, potentially leaking sewers running along creeks in D.C.’s parks. There are projects planned at Fenwick Branch and Pinehurst Branch in Upper Northwest, and along Watts Branch in Northeast. And there is a huge project to rehabilitate nearly 4 miles of sewer lines in Glover-Archbold Park, from the Potomac River to Van Ness St. NW.

What happens with the Soapstone project could set a precedent for these other projects still in the planning stages.

Why are there sewers in Rock Creek Park?

To some hikers, joggers, or dog-walkers, the middle of a national park might be a surprising place to find a sanitary sewer. But sewer lines run along many tributaries in Rock Creek Park, and along the scenic Rock Creek itself. It creates an odd juxtaposition: natural beauty and the smell of raw sewage.

The explanation for the sewers’ location in the park has to do with a couple of factors: gravity, and D.C.’s unique history as a federal city.

When the District’s fist sewers were put in in the early 1900s, engineers found gravity was an efficiently and cheap way carry sewage out of the city.

“Gravity was free,” Lienhard explains.

Mother nature had already found the best routes for gravity-fed water to flow — carving creek beds over the course of thousands of years. Engineers simply followed nature, laying down sewer pipes next to the creeks.

The hilly terrain around Rock Creek was already owned by the federal government, which, at the time, was also responsible for public works in the District, including building sewers.

“The pipe actually predates the National Park Service and DC Water as an entity,” says Elledge.

Project could cause ‘irreparable harm,’ neighbors say

To repair the sewers, DC water plans to close the park for two years, cut down as many as 370 trees, and reline the old pipes using an industrial process that critics say has lead to numerous illnesses of workers and bystanders.

I took a walk through Soapstone with Marjorie Share, a longtime resident of Forest Hills, the neighborhood just north of the park.

“Standing here, looking at the rear of the apartment buildings in very close proximity, one wonders, if the workers have been getting ill, how does this affect nearby residents? Small children and businesses who are here breathing the same air?”

The park is bordered on the west side by Connecticut Ave., lined with tall apartment buildings, restaurants, and a daycare center.

“What happens in the park does not stay in the park. This is their backyard,” says Share.

Share first became interested in the project when she heard about how many trees would be cut down. “I just wondered whether there were alternatives. There had to be other solutions,” says Share, who has written about the Soapstone project for Forest Hills Connection, a neighborhood news site.

As she looked into alternatives, Share became concerned about the technology DC Water planned to use to repair the sewers, called “cured-in-place pipe” or CIPP. Her research led her to the work of Andrew Whelton, an engineering professor at Purdue who has studied the process.

Whelton says there have been many cases of people being sickened by CIPP work. It involves numerous toxic chemicals, which are often released into the air. In one recent case in Wisconsin, a middle school was evacuated and 64 students and staff needed medical attention after what appears to be chemical exposure from a nearby CIPP project.

Whelton explains CIPP is basically a mobile plastic pipe factory – but without the protections regulators would normally require. Operators insert resin-coated liners into old pipes, then harden the resin using either steam, hot water, or UV light.

Whelton says this sort of plastic manufacturing would typically be done in a factory with chemical fume hoods and full personal protective equipment. “You’re taking it and you’re bringing it into neighborhoods next to daycare centers and hospitals and all these other sensitive populations. And you’re not capturing the waste, you’re actually blowing it on purpose into the environment.”

Whelton says CIPP — though it has been a common technology for several decades — has flown under the radar of regulators at the Environmental Protection Agency and state agencies.

“If you’re a pipe manufacturer and you’re going to create PVC pipe, EPA knows where you live — EPA knows where you are manufacturing. And so they say, ‘I know you’re going to pollute, so we need to measure how much you’re going to pollute and make sure that you don’t exceed some threshold.'”

CIPP operations, on the other hand, are unchecked, says Whelton, and not required to get air pollution permits. “They’re driving around cooking plastic, blowing the waste into the air,” Whelton says.

After pushback from neighbors in Forest Hills, DC Water announced in January they’re switching to a different type of CIPP – rather than using steam to cure the plastic pipes, as they originally planned, they’ll use hot water. They say because of this change the air pollution Whelton has documented won’t be an issue. And water pollution will be taken care of at DC Water’s Blue Plains sewage treatment plant.

But Whelton says water-cured CIPP can still cause air pollution, as hot water, laden with toxic chemicals, volatilizes inside sewer pipes. And neighbors still aren’t satisfied the technology is safe.

“We’re saying time out, people,” says Dipa Mehta, the advisory neighborhood commissioner for the area. “There is no way to reverse the irreparable harm that would occur by forging ahead with this technology.”

The local ANC passed a resolution in January calling on DC Water to hit pause on the project. This week, the ANC passed an emergency resolution, asking Councilmember Mary Cheh (Ward 3) to secure a stop-work order to keep the project from moving forward.

Mehta says nobody is questioning the need for the sewer rehabilitation, and the ANC is not asking for a years-long delay. But, she says, DC Water has not fully analyzed the alternatives — particularly UV-cured CIPP, which does not create the same level of pollution.

Cheh wrote a letter to the director of the District Department of Energy and Environment in January, echoing residents’ qualms about the project. Professor Whelton’s findings about CIPP pollution are “deeply concerning,” Cheh wrote, “especially since DC Water intends to use this technology not just in Soapstone Valley, but across the District.” She asked whether it would be prudent to have a third party conduct a more thorough environmental assessment of the various CIPP technologies before proceeding.

Richard Jackson, senior deputy director of DOEE, wrote back to Cheh on Feb. 17. Jackson said the agency had completed a review of the water pollution impacts of CIPP, and found the Soapstone project will have “minimal or no impact on surface and groundwater.” In terms of air pollution, Jackson wrote, DOEE is still reviewing the impact that the hot-water cured process will have. Preliminarily, he said, it appears the project may not need an air quality permit due to its expected lower emissions compared to steam-cure, which would have required a permit.

Jackson also said the environmental assessment appears to have been prepared in accordance with federal law, and that while DOEE had been consulted multiple times over the years on the assessment, the agency has “no regulatory oversight role to play in that process, nor authority to require a second assessment under District law.”

More delay could also harm human health

Both the National Park Service and the DOEE support the project and say it will improve water quality.

“The National Park Service looks forward to DC Water’s Soapstone Valley Park sewer rehabilitation project getting underway because Soapstone Creek has one of the highest levels of fecal coliform bacteria of any of the Rock Creek tributaries,” NPS spokesperson Cynthia Hernandez wrote in an email.

Hernandez noted that the project’s environmental assessment looked at many alternatives for the sewer rehab, including the possibility of rerouting the pipes outside the park. “In the end, the NPS selected the alternative to reline the pipes with a cured-in-place method that would minimize impacts to Soapstone Creek, the park’s trees and trails, and underground historic resources.”

Likewise, a spokesperson for DOEE provided a statement backing the sewer project.

“DOEE is confident that this important work will result in improved water quality for the Rock Creek watershed. DOEE continues to review DC Water’s proposed plans to ensure that all applicable requirements are met and the work is protective of the public and environment. ”

Both NPS and DOEE declined interview requests for this story.

Jeanne Braha, with the nonprofit Rock Creek Conservancy, says the project is long overdue for this polluted waterway. Water quality testing conducted by the group over the past three years showed the Soapstone Creek within federal E. coli bacteria standards zero percent of the time.

“We always need to make sure that human health is protected,” says Braha. “I think the concern here is that human health is at risk from the water and the water quality issue that continues to fester with the sewers right now.”

More delay won’t be good for Soapstone Creek, she says, or for the other tributaries in line for sewer upgrades.

William Elledge says DC Water defends the utility’s pivot to water-cured CIPP. “From an environmental impact perspective, the UV versus the water cure, that’s not a stark difference there,” Elledge says. And he says UV-cured CIPP is not well suited to the steep, difficult-to-access terrain in Soapstone Valley.

Elledge says DC Water has already revised the project numerous times in response to feedback from the community. The initial proposal, he points out, would have involved cutting 800 trees, not the 370 currently slated for removal.

At this point, DC Water is planning to move ahead with the project, starting with marking trees to be cut down this week. But neighbors are still pushing for them to reconsider using UV technology for curing the sewer pipes. DC Water is holding a virtual meeting about it Thursday evening.

This story was updated to include new information from DOEE’s letter to Councilmember Cheh.

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston