Despite making up about half of all births in recent years, Black birthing people in D.C. made up 90% of birth-related deaths, according to a new study from a city-supported review committee — underscoring the severity of the city’s maternal health crisis, particularly for Black women.

“Things that we know about maternal mortality and women who are at increased chance of dying from a pregnancy-related cause, is that being structurally and socially disadvantaged and marginalized is a huge contributor to risk,” says Dr. Christina Marea, a cofounder of the committee. “Factors that put particularly Black birthing people at a disadvantage, like structural and historical racism, underinvestment in communities, the carceral state that treats Black families as criminalized for things that white families wouldn’t [be]…all of these combine and contribute.”

The study, conducted by the Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC), reviewed all pregnancy-associated deaths in D.C between 2014 and 2018. The group – consisting of local experts and residents – first formed in 2018, after a legislative push from Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen and calls for the city to seriously investigate the District’s maternal mortality crisis. For years, D.C. has reported a maternal mortality rate well beyond the national average. According to the United Health Foundation, the city’s maternal mortality rate in 2018 was roughly 36 per 100,000 live births, compared to the national rate of 20.7 – and the gap widens further for Black birthing people. In 2018, the national Black maternal mortality rate was 47.2 per 100,000 live births; for Black birthing people in D.C., the rate was 70.9.

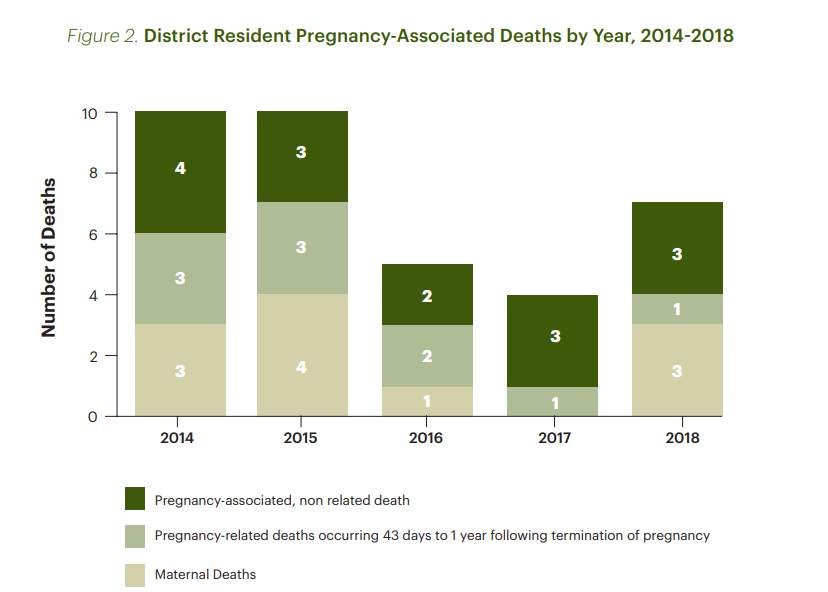

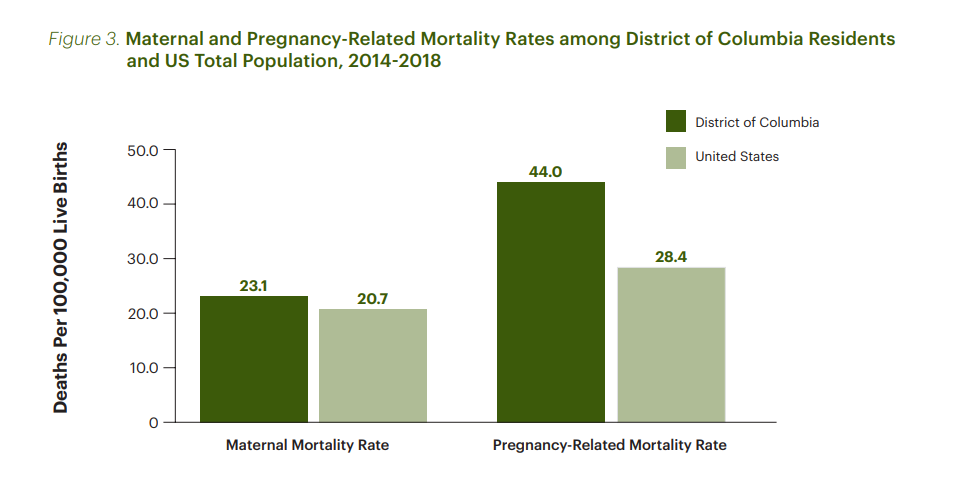

The MMRC chaired by Marea and Aza Nedhari, the Executive Director of Mamatoto Village, a collective of Black birth workers in Northeast D.C., released the first of its annual studies on Tuesday, providing further insight into the city’s crisis by reviewing all 36 pregnancy-associated deaths in the city between 2014-2018. The city-wide maternal mortality rate over that five year period was roughly 23 – meaning for every 100,000 live births, the city recorded 23 maternal deaths. Maternal death refers to the death of a person while pregnant, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, for any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy and its management – but not from an incidental or accidental cause. Over that same period, the national maternal mortality rate fell somewhere between 20 and 21.3, according to the study.

D.C.’s pregnancy-related mortality rate was nearly 44 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to the national rate of 28 over the same period. Unlike maternal death, a pregnancy-related death refers to any death within one year of pregnancy from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiological effects of pregnancy.

The report outlined wide disparities by race and geography. While Non-Hispanic Black birthing people made up 90% of the city’s pregnancy-related deaths, white residents reported no pregnancy-related deaths, despite comprising 30% of all births in the city. Wards 7 and 8 residents comprised 70% of pregnancy associated deaths, while residents of wards 2 and 3 reported no pregnancy-associated deaths in the reporting period.

“The disparities and the statistics are very real and very concerning, and they are very much along racial lines — racial lines that are underlined by these social and structural causes,” says Marea. “There’s nothing about Black birthing people that makes them more likely to die, it’s the environments to which they’re exposed in our social, environmental, and health systems.”

The committee’s review also looked at the most prevalent causes of death in pregnant people, top among them being cardiovascular diseases, heart diseases, or pregnancy-related complications, like hemorrhage or uterine rupture. These conditions (which are already more prevalent in Black D.C. residents, pregnant or not, than in white residents) reflect layers of structural racism, according to Marea, and are driven by the same “social determinants of health” that influence pregnancy outcomes. Social determinants of health refer to environmental factors like economic stability, housing, and discrimination (among others) that affect a wide-range of health outcomes.

The disparity in D.C.’s maternal mortality rate mirrors disparities in other health conditions — namely COVID-19 — where underlying illnesses like heart disease and hypertension put residents at highest risk of dying. By May of 2020, Black Washingtonians made up 80% of coronavirus deaths, despite making up less than half of the population. In early 2022, as the omicron wave swept through the region, Black D.C. residents accounted for 84% of deaths.

“Yes, there are increased rates of pre-existing and pregnancy-related cardiovascular diseases that contribute to mortality,” says Marea. “But let’s go farther upstream than that, and say ‘why are young women at such high risk of developing heart disease or other cardiometabolic disorders at such a young age?’ Well, we look at these social and structural factors that increase the chronic stress that their bodies are under.”

A data point not included in the MMRC’s review, but in which similar disparities appear, is the city’s preterm birth rate. Preterm births occur when a baby is born before the 37th week of pregnancy, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and are the second-leading cause of infant mortality in the nation. D.C.’s preterm birth rate improved from 10.4 in 2019 (equating to a grade of D+) to 9.8 in 2020, a rating of a C, according to the March of Dimes. But the disparity ratio between preterm births of Black and white babies did not improve.

Since the formation of the MMRC in 2018, D.C. lawmakers have passed a number of initiatives aimed at improving pregnancy outcomes and bolstering support for mothers in the city. The 2022 budget includes investments in a D.C. Medicaid plan to reimburse doula services starting this fall and funding for transportation costs to medical visits. But the MMRC’s report outlines further solutions — like increasing the availability of inpatient social workers to support a patient during hospitalization, and large-scale changes to the transition from in-hospital care to in-home care.

“So many of our patients in our case reviews, they have multiple intersecting levels of vulnerability,” says Marea. “Often there’s an aspect of isolation and lack of social support, and also a medical complexity that can be really difficult to navigate. One of the things that we as a committee hope for our prenatal patients, and particularly for our perinatal patients with complex medical or social needs, is that they have someone who is proactively reaching out to them to ensure that they understand their diagnosis.”

The committee, still playing catch up from time lost during COVID, plans to release its report on 2019-2020 data in July. Marea says as the committee continues its work, they’re looking to implement an interviewer program to speak with families who lost a loved one during or related to pregnancy. Their also hoping to expand their research on maternal morbidity, which refers to severe unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery that result in short or long-term health consequences.

“We have to have the political will and public health approach of moving farther upstream, of doing better care of our children who are involved with Child Protective Services in the foster care system, taking better care of families that experience housing insecurity, having earlier screenings for children and adolescents who are exposed to adverse childhood experiences, addressing excess stress within our communities related to transportation, excess policing, community violence, and environmental stressors,” says Marea. “So women at 23-years-old don’t have heart disease because they haven’t already accumulated so much physical, psychological, environmental and structural stress that their bodies are at risk for these pregnancy complications.”

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick