Ask any campaign staffer or seasoned candidate what matters most in elections, and they’ll likely tell you it’s actually getting voters out to the polls.

But the somewhat sudden advent of mail voting in D.C. has scrambled time-tested Election Day get-out-the-vote efforts, forcing candidates for races up and down the ballot to rethink how and when they reach voters — and what the ultimate results will be once polls close on June 21.

“It’s going to change how you drag voters out to the polls, because you don’t know how many people are actually going to vote in person,” said Mayor Muriel Bowser, who voted early in-person on Thursday and has run campaigns for local and citywide seats for more than 15 years.

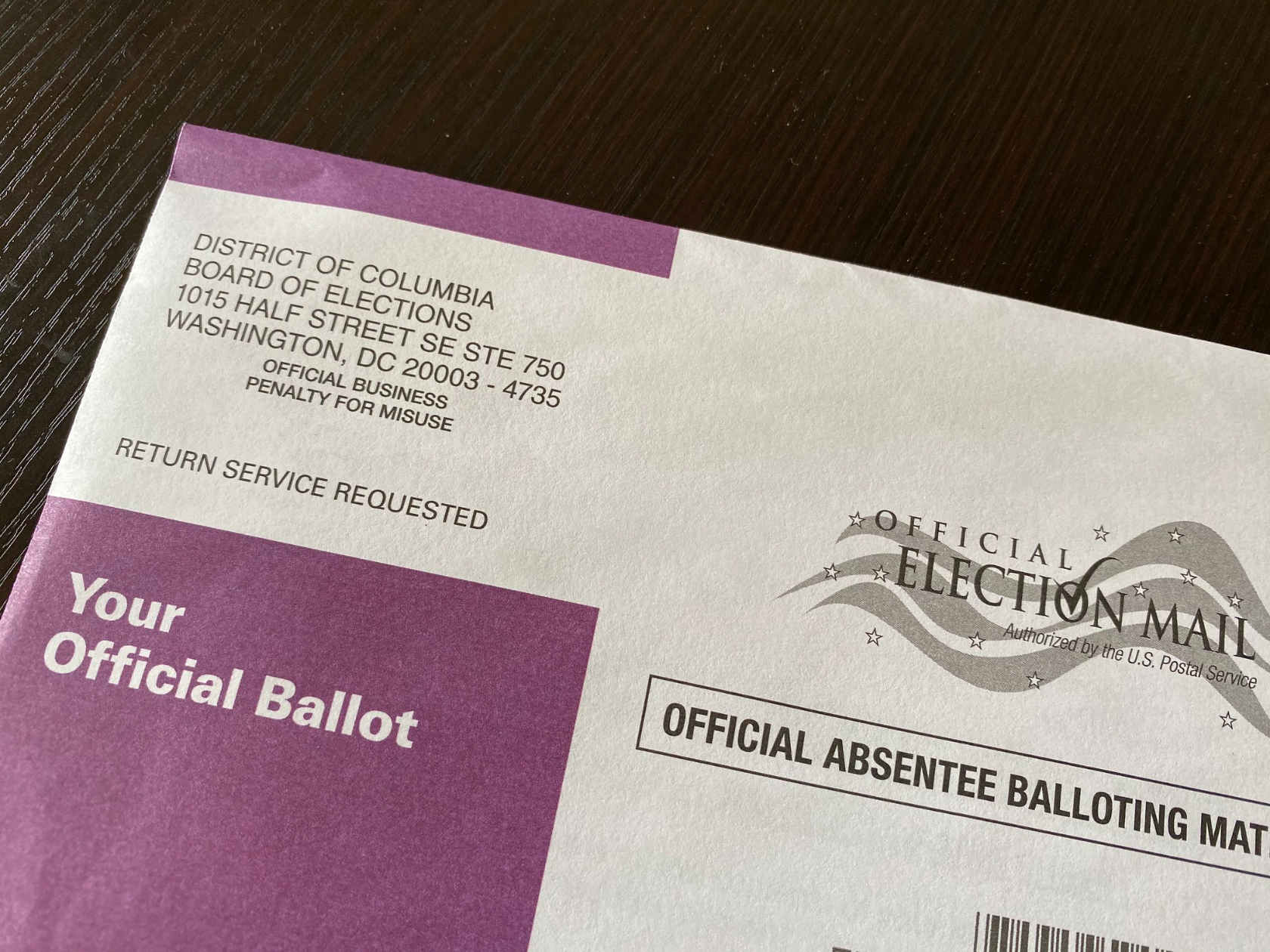

This is the second election cycle where every registered voter in D.C. has been sent a ballot in the mail, but this is the first time that’s been the case during a primary — and a mayoral race at that. The D.C. Board of Elections sent out 409,000 mail ballots in mid-May, marking the start of a voting season that over the decades has expanded from a single day to the current six weeks of voting, which includes a week-long in-person early voting period. (That period ends June 19.)

In the 2020 general election, two-thirds of D.C. voters opted to use mail ballots. This year, that dynamic seems to be shifting even further in the direction of mail voting. As of Thursday, 44,075 residents had voted in the primary — and 85% of them did so with mail ballots. (Primary turnout has ranged from 89,000 to 114,000 in total in recent years.)

That reality has been evident at many of the city’s 39 early voting centers, some of which have seen just a handful of voters every day. At the Ferebee-Hope Recreation Center in Ward 8, only five people voted on Thursday; at Alice Deal Middle School in Tenleytown, nine people cast ballots. Even at the city’s busiest early vote center — the Turkey Thicket Rec Center in Ward 5 — only 725 voters have cast ballots in the seven days of early voting so far.

That dearth of early in-person voters has changed the dynamic at vote centers, where traditionally campaigns would have volunteers on hand to make last-minute pitches to voters walking in to cast their ballots. Now, there seem to be more campaign signs than actual voters.

“We’re seeing a majority of people are coming to the polls already having voted, they’re just dropping off the ballot. I think in a couple more election cycles all of this will be obsolete,” said Vincent Orange, a candidate for the Ward 5 seat on the D.C. Council, as he stood outside the Turkey Thicket early vote center on Thursday amidst a crowd of campaign signs and volunteers.

During the traditional election cycles of years past, campaigns would use staff and volunteers to knock on doors in the lead up to Election Day, and then invest in a more coordinated day-of, get-out-the-vote operation — sometimes paying for buses to ferry reliable voters to and from the polls. But candidates now say that such an operation is less feasible; many voters may have cast their ballots before Election Day, and there’s simply a larger universe of possible voters to reach since everyone got a ballot in the mail.

“It required more strategic thinking around how we were going to reach every voter instead of the reliable super voters,” said Zachary Parker, another of the candidates in the competitive Ward 5 race. “Everyone is fair game just given that everyone is going to receive a ballot.”

“Get-out-the-vote for us has been [active] since people had their ballots,” said Bowser.

“Our field efforts started long before mail-in ballots and early voting started,” added Luz Martínez, the campaign manager for D.C. Councilmember Robert White’s (D-At Large) mayoral campaign. “We’ve put in a lot of work to reach voters and the result is how competitive the race has gotten.”

The new campaign dynamics have also pushed candidates to rely more heavily on campaign mailers, which have barraged voters in recent weeks. “The mailers just speak to the reality that we know you have to reach as many voters as possible,” said Parker. (More campaigns are also sending more mailers because they can afford them; the city’s new public financing program has leveled the playing field when it comes to fundraising, say many candidates.)

But for all of the growing pains, proponents of mail voting say it’s simply more convenient for many voters.

“It’s more difficult now because you’re trying to catch people at different stages,” added Gordon Fletcher, another of the Ward 5 contenders. “From a candidate’s perspective it’s definitely tougher, but from a democracy perspective it’s better.”

“This to me feels good because you still have an opportunity. It’s not like people miss the one day so they can’t [vote],” echoed Faith Gibson Hubbard, another of the Ward 5 candidates.

But the data on whether mail voting leads to higher voter turnout seems mixed. While states like Oregon and Washington have reported higher turnout since moving to universal mail voting, a 2017 study of California localities that switched exclusively to mail voting showed a slight decrease in participation. In the 2020 general election — which was conducted largely by mail — D.C. saw only a slight uptick in turnout relative to similar elections before it.

“What we don’t know is if more people will vote, which we hope, or if people are voting differently,” said Bowser.

Those issues aside, every candidate at Turkey Thicket on Thursday opined that mail voting is likely here to stay. “I think the time has come for mail voting because of the pandemic,” said Orange. “People are inclined to do more things at home.”

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle