D.C. is reporting the most monkeypox cases per capita in the U.S. as officials undertake another vaccination campaign, constrained by federal supply woes and sluggish testing.

As of Monday morning, D.C. reported 122 cases – the most cases per residents of any state in the U.S. – and has identified more than 530 close contacts of those cases since the first case was detected back in the city in early June. Of those cases, 63% occurred in white residents who identified as male, and 24% in Black residents who identified as males. Residents who identified as gay make up 92% of the city’s current cases, and the majority of men are in the 30-34 age range, according to DC Health.

With vaccine supply from the federal government still limited and testing nationwide slow to ramp up, the city is focusing its awareness and vaccination efforts on groups most at-risk of contracting the virus, while attempting to avoid the logistical complications and equity gaps that beset the city’s COVID-19 vaccination rollout.

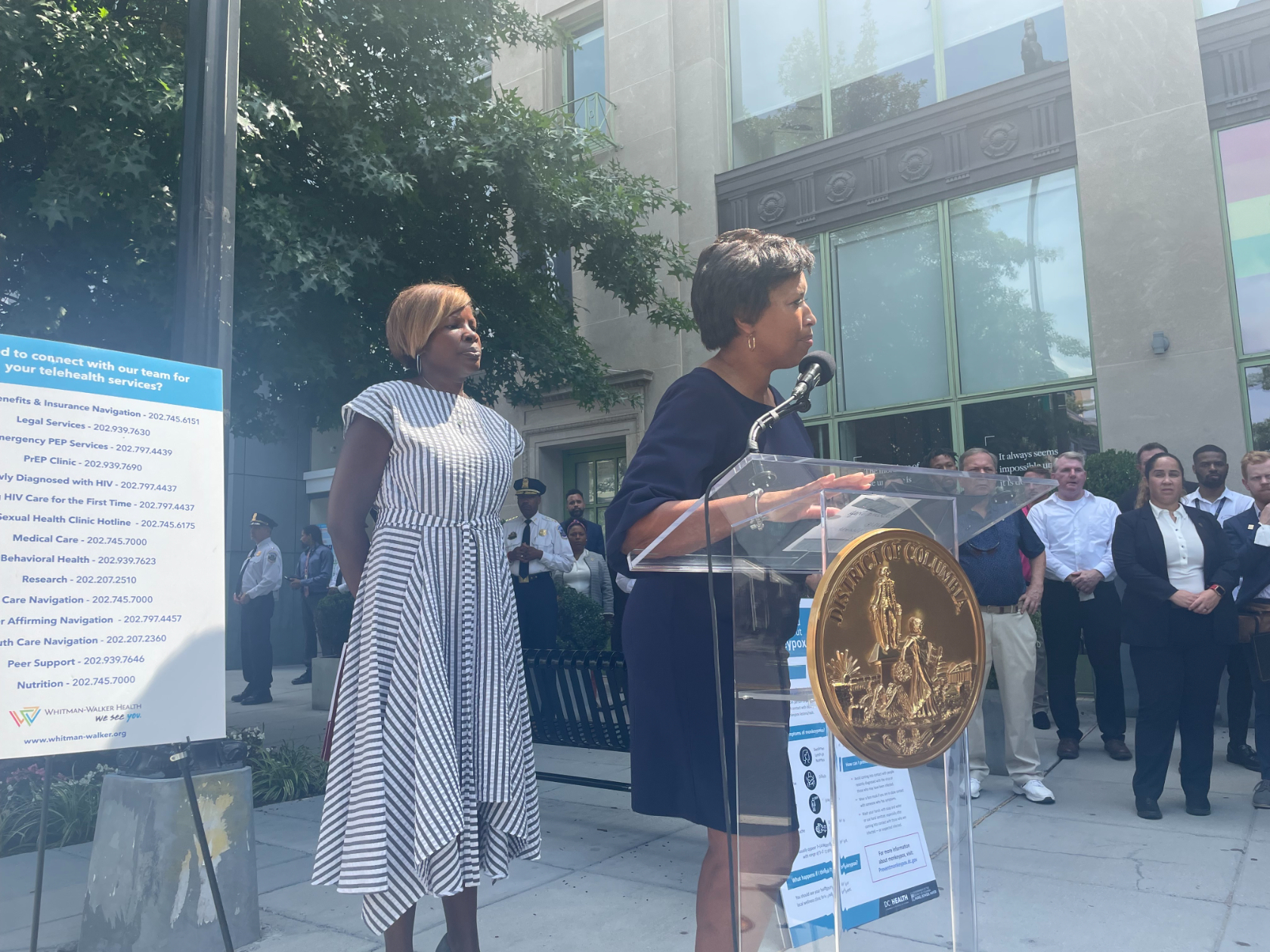

“It is extremely important to note that while the majority of the cases during this outbreak are occurring in individuals who identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community, this is not a disease of the LGBTQ+ community. Anyone can contract monkeypox,” said outgoing DC Health Director LaQuandra Nesbitt at a press conference Monday morning. “This is extremely important that we do not create stigma at this time, and that we encourage individuals to be on the lookout for symptoms.”

MPV first began circulating in the U.S. in early May. A virus in the same genus as smallpox, which was eradicated in the 1980s, MPV initially presents with flu-like symptoms (fever, muscle aches, fatigue) before presenting a rash. It’s primarily spread through close contact with an infectious rash, sore, or lesion, or through prolonged face-to-face contact, including kissing, cuddling, and sex, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while men who have sex with men make up the majority of D.C.’s cases, anyone can get MPV or spread it. Sexual orientation and gender identity alone do not put a resident at high risk of contracting the virus — a potential exposure to the virus does.

It’s likely that the current count of more than 120 citywide cases is an underestimate, as testing for MPV was slow to get started in D.C. and across the nation. Last week, more MPV testing became available through both Labcorp and Quest Diagnostics, meaning now nearly every provider in D.C. should be able to administer the test. Unlike COVID, which can be tested through saliva, the MPV test requires a swab of an open sore or rash.

“It doesn’t have to be done in emergency rooms, it does not have to be done in a sexual health clinic. It could be done in your primary care office,” Nesbitt said Monday. “And we’re working with all of the primary care physicians, licensed physicians and health care providers in the District of Columbia to offer this testing … it’s important to identify cases of monkeypox very early, because that’s one of the best ways for us to prevent ongoing spread.”

Officials are also working to increase the local availability of a certain antiviral that’s shown to be helpful in reducing pain from a MPV infection, but again, the process is limited by a bureaucratic chain of orders and shipping. D.C. needs to order the drug from the federal government, and then local doctors need to order the drug from DC Health. Last Friday, DC Health senior official Patrick Ashley told D.C. councilmembers that the city had given 25 patients the treatment, and they reported it helped manage pain.

While there’s no treatment for MPV specifically, its similarity to smallpox means scientists have vaccines and antivirals that can help prevent and treat the illness. According to Nesbitt, D.C. has so far received roughly 8,300 doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine (made in Denmark) from the federal government, with 4,000 additional doses expected to come later this week – amounts allocated by the feds based on D.C.’s current case load and available quantities. It’s still not enough to meet demand, officials say.

“We are aware that supply is limited, we have been very vocal,” Nesbitt said. “We have seen the pace at which the doses coming to the U.S. from Denmark increase, [but] we would like it to still be faster.”

When the first doses came to D.C. in late June, the city’s distribution system was fairly last-minute: DC Health would announce on social media in the morning that appointments (typically only a few hundred) would open later that afternoon. Each time, the appointments were booked up within minutes of coming online – potentially leaving out residents who didn’t have the ability to sit and refresh a website in the middle of the afternoon, or who had missed DC Health’s first message entirely.

Last week D.C. Health replaced that booking system with a pre-registration website similar to the one used in the first months of the COVID vaccine rollout, opening up 3,000 appointments for booking last Thursday. Residents fill out a form attesting to their eligibility, and when an appointment is available, will receive an email with 48 hours to claim it. Vaccinations take place Friday through Sunday at two locations in the city, from 1 pm. to 8 p.m.

Currently, the city is limiting eligibility based on an “expanded post-exposure prophylaxis” strategy, targeting those who, based on the demographics of current cases, may be most likely to have been or to become exposed to MPV. Currently, those in that group are anyone over the age of 18 who meets the following criteria:

- Gay, bisexual, and other men 18 and older who have sex with men and have had multiple or anonymous sexual partners in the last 14 days); or

- Transgender women and nonbinary persons assigned male at birth who have sex with men; or

- Sex workers (of any sex); or

- Staff (of any sex) at establishments where sexual activity occurs (e.g., bathhouses, saunas, sex clubs)

DCist/WAMU has asked DC Health why transgender men, or non-binary people assigned female at birth have been excluded from this initial group, but the agency did not respond immediately.

Given the personal nature of the questions asked on the pre-registration survey, Nesbitt said the health agency is working with providers to make sure residents feel comfortable seeking treatment or vaccination, and is encouraging anyone who wants a vaccine, even if they’re not currently eligible, to sign up.

“We have seen overwhelming interest in the vaccine, and we have seen people come forward,” Nesbitt said. “We have a way of posing questions that make people feel very comfortable … these are simple facts, right? There’s no judgment. There’s no editorializing associated with it.”

In a call with councilmembers on Friday, Ashley told councilmembers that the pre-registration system is randomized, meaning it won’t matter when an individual signs up, so long as they’re deemed eligible. As of Monday, 2,600 of the 3,000 pre-registration system appointments were booked.

The city is also reserving vaccines for those who have been directly exposed to a confirmed case. Similar to contact tracing, the city identifies individuals who have been exposed and contacts them to administer a vaccine. So far, more than 136 people have been vaccinated as close contacts, according to Nesbitt.

A small number of doses have been administered through clinics at the city’s partner providers, like Whitman-Walker (where officials held Monday’s press conference) and Us Helping Us, according to Nesbitt, but additional clinics depend on supply and when that vaccine supply arrives from the federal government. (Because the vaccine is a two-dose series, a portion of the vaccine supply needs to also be reserved for second doses, adding a complication into vaccination planning.)

District officials (and most public health officials in the U.S.) are attempting to get out in front of a virus while still in year three of the COVID-19 response that’s been criticized ten times over for breeding inequity, widening existing racial and socioeconomic gaps, and illustrating the flaws of America’s public health infrastructure. Asked on Monday what lessons the city learned from COVID-19 that carry over into D.C.’s MPV response, Nesbitt pointed to the vaccine pre-registration system, which is now not based on location but demographic information and eligibility.

“We learned [during COVID vaccination] that people with resources and means would drive into communities of color that they had never gone to ever before to get those vaccines … people came and snatched those vaccines up. You saw people from Ward 3 go to Ward 8,” Nesbitt said. “And the public view that as if the health department did not have an equitable strategy. Now, we are creating where the scheduling is done for people of color, and not just simply by location.”

Ashley and Nesbitt have also pointed to the city’s attempts to reach individuals that may not be tuned into social media, where DC Health has posted much of its MPV information and vaccination information. According to Ashley, the agency is meeting weekly on Thursdays with LGBTQ+ community providers, and Nesbitt said the city is also considering hosting something related to MPV prevention at the city’s first homeless shelter for adults.

Previously:

D.C. Launches Pre-Registration System For Monkeypox Vaccinations

What To Know About Monkeypox Vaccination In The D.C. Region

D.C. Is Making Limited Number Of Monkeypox Vaccines Available

What To Know About Monkeypox In The D.C. Region

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick