Ruth and Ronald heard rumors when they arrived at the Texas-Mexico border that people in D.C. were offering free help to migrants like them. The couple from Venezuela, who declined to give their full names so as to not jeopardize their asylum application, were relieved to learn the rumors were true.

When they arrived at Union Station on Friday, the pair and their four kids say they were greeted by local volunteers and nonprofit staff, who offered food and other support. A volunteer purchased their flight to Florida, where they plan on meeting Ruth’s cousins — then she offered up her home to the family for the night, sheltering and breaking bread with them as they waited for their flight on Saturday evening.

Their experience in D.C. was night and day with Texas. “It was tougher because in the border there are military, so they treat you like military,” Ronald tells DCist/WAMU at a church downtown that’s become a base of operations for volunteers helping the migrants.

“I was a little down. But once we got here, the way they treated us here, I felt good,” he says in Spanish. Ronald gestured over to his wife who was trying to calm their restless 1-year-old. “If we didn’t have her family, I told her that we would stay here. We would stay in Washington. I felt a good vibe here.”

Local volunteers have been working hard since April to create the vibe that Ronald is describing. But as time has worn on, and red-state governors continue to send several thousand migrants into D.C. at all hours of the day to protest President Joe Biden’s immigration policies, those volunteers tell DCist/WAMU that their capacity to welcome people is increasingly unworkable.

But neither the local nor the federal government are willing to step up, volunteers say, and migrants are having to go to area homeless shelters or are even being deserted at Union Station, as donations dwindle and fatigue sets in. D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser has cast this as a federal problem with a federal solution — a characterization that angers volunteers because they say that means Bowser, who’s called D.C.a sanctuary city, proves to be no different than Texas Gov. Greg Abbott or Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey who are trying to offload migrants on the Biden administration.

“Washingtonians, as people, are here, present, but their government is not here,” says Isaias Guerrero, a volunteer with the Migrant Solidarity Mutual Aid Network, a grassroots network led by Black and brown femmes and immigrants that represents over 20 local social justice groups.

“We don’t see anybody from Mayor Bowser’s office here. We don’t see anybody from the Office of Latino Affairs here to say ‘Welcome, how can we support you’ even if it’s with like waters,” he continues. “People just want to wash their hands because this is seen as a hot potato. But what it should be seen as is an opportunity for us to actually create a model of being welcoming.”

In a statement to DCist/WAMU, the mayor’s office says they’ve worked with the Biden administration to provide a federal grant for an international nonprofit called SAMU First Response, which is sharing the work with volunteers at Union Station. “We will continue to call on the federal government to address the immigration issue holistically and to more immediately and effectively provide supports and services for individuals and families who are being bussed,” the statement says.

SAMU — a nonprofit that’s provided similar care to unaccompanied minors at the southern border — says its team of 25 paid employees is overwhelmed by the number of migrants being dropped off at Union Station, along with the frequency of their arrivals. Buses come six days a week, so SAMU has relied on volunteers to supplement labor and resources or else migrants will be stranded at Union Station.

Volunteers have said for months now that they and a few nonprofits should not be responsible for what’s effectively become a border operation and resettlement for asylum seekers. Volunteers say the local government, in particular, cannot ignore the crisis for much longer: Roughly 10-15% of migrants bused here end up staying in D.C., both volunteers and nonprofit staff tell DCist/WAMU.

But ultimately, it continues to be volunteers and nonprofit staff who try to ensure that migrants don’t feel like a burden to D.C., as Abbott sought to do. “With our nation’s capital now experiencing a fraction of the disaster created by President Biden’s reckless open border policies that our state faces every single day, maybe he’ll finally do his job and secure the border,” Abbott’s press secretary, Renae Eze, says in a statement to DCist/WAMU. Abbott’s office says Texas bused over 5,400 migrants to D.C. and declined to say when they’ll stop sending people. Arizona governor Ducey started sending buses to the city in May.

With the exception of Montgomery County, which secured a 50-bed facility for SAMU to use for shelter, local governments have declined to spend any dollars or resources on migrants. Bowser has instead repeatedly punted responsibility to the federal government. “We have to be very focused on working with D.C. residents who are homeless and have a right to shelter in our city, especially as we prepare for the winter months,” she said at a July 18 press conference. “We know we have a federal issue that demands a federal response.”

D.C. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton agrees with Bowser.“I believe that the response lies with the federal government,” she told DCist/WAMU. She also believes it’s “futile” to ask Abbott and Ducey to stop busing migrants to the city. “They are not sending [buses] to the District of Columbia. They’re sending these buses to the nation’s capital. So nothing I can say would have any effect upon them,” she says.

Norton did introduce an emergency appropriations bill that would provide additional funding for the FEMA program that enabled the grant to SAMU. But she declined to say how much money she’s requesting, or discuss the bill’s path to passage.

Madhvi Bahl of Sanctuary DMV and Migrant Solidarity Mutual Aid Network likened the mayor’s comments to the conservative talking point of immigrants stealing jobs from citizens. “She’s pitting people against each other,” says Bahl. “If you pit the oppressed communities against each other, then maybe they’ll ignore the person in power who’s not doing anything. No one is falling for it.”

D.C. Councilmember Brianne Nadeau of Ward 1, who organized a letter from a majority of the D.C. Council asking the Bowser administration to do more for the migrants, says inaction from the District has profound consequences. “Inevitably, if people have nowhere to go, they’ll end up sleeping outside or coming into homeless shelters,” she tells DCist/WAMU. “I think we’ve worked incredibly hard to end homelessness here in the District of Columbia, and we certainly don’t want to see any more people become homeless on our watch.”

Migrants have already turned to several homeless shelters in D.C., with some of them being turned away in recent days because shelters did not have enough beds, according to Bahl. One overnight emergency shelter confirmed that a few migrants have stayed there and noted that the facility frequently reached capacity even before migrants began arriving on the buses. (DCist/WAMU agreed to not name the shelter as to prevent unwanted attention.)

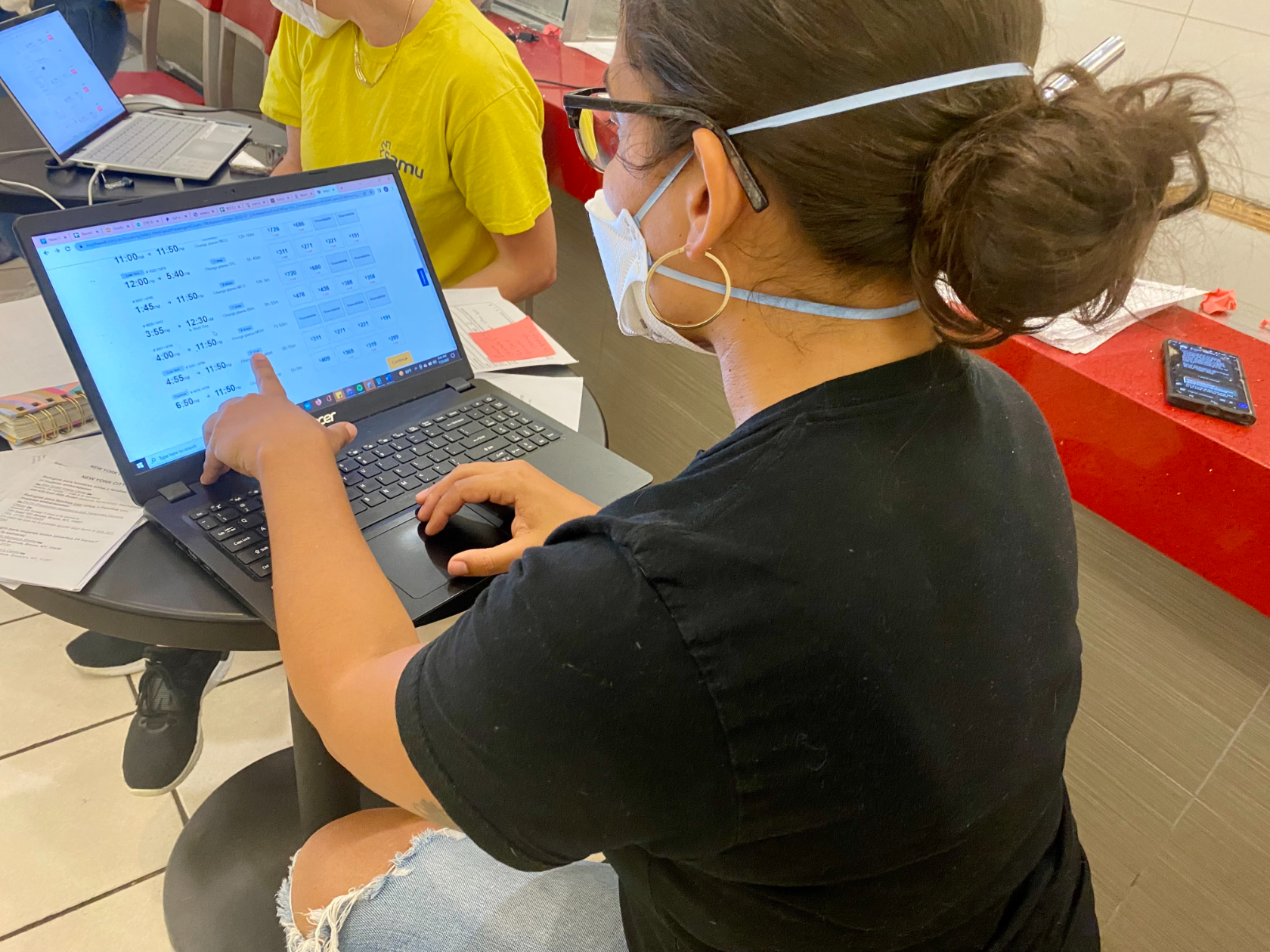

Of the 70 migrants that arrived at Union Station from Texas early Saturday morning, 15 have no immediate plans to leave D.C. Mutual aid volunteers and SAMU staff did intake in the station’s food court, meeting one-on-one with each migrant to assess their needs.

One young man from Venezuela told DCist/WAMU that he plans to go to New York City, but he doesn’t know anyone there and will likely have to stay at a homeless shelter in that city until he figures out what to do next. An older woman, also from Venezuela, was too worried about her husband to say what her next move was — the couple were separated in Texas and he was being bused the next day. She’ll likely stay at a shelter in D.C.

“It is a lot of work. … and it can lead to burnout,” says volunteer Juana Osorio, who led the welcome that morning. “It is not sustainable to just continue to do it by ourselves without the support or funding or the government really stepping up.”

Volunteers outnumbered SAMU staff that Saturday, so the groups cooperated. Volunteers bought 30 bus or plane tickets while SAMU purchased 27. Due to the constraints of its federal grant, the nonprofit only pays for 30% of transportation costs for a given day’s arriving migrants.

While volunteers help migrants who stay in D.C. indefinitely — including by signing up individuals for local resources like health care or school — SAMU can’t help migrants resettle in the region, according to Tatiana Laborde, the nonprofit’s director of operations. “That’s beyond the emergency food and shelter program [we’re operating], and that is beyond any of the agencies that usually operate under these guidelines at the border,” she tells DCist/WAMU. “This isn’t a resettlement program.”

While mutual aid volunteers and nonprofit staff worked together on Saturday, there is some tension between the groups. Multiple volunteers say the SAMU isn’t making the most of the $1 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, while SAMU says they are doing their best to manage a challenging situation.

“We have been given a grant for FEMA that has a specific set of guidelines on how we operate. And that’s why the work has to be divided. Mutual aid groups work under different rules,” Laborde tells DCist/WAMU. “It is not the expectation of FEMA that we take care of everybody — it is to provide support to as many [people we can].”

At a Friday meeting held by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, lawmakers invited Migrant Solidarity Mutual Aid Network and SAMU to speak about their efforts so they could learn how the local governments can help. “We need to have a regional response,” Montgomery County Councilmember Will Jawando (D, At-Large) said during the meeting. “This is an issue that we didn’t create but that we have to deal with.”

During the meeting, government officials explained what they’re already doing. Dira Treadvance of the Montgomery County Health Department said they helped dozens of migrants who settled in the region while a representative from FEMA who attended, MaryAnn Tierney, effectively told governments and nonprofits to capitalize on the federal grant.

Amy Fischer, who works as the advocacy director for the Americas at Amnesty International but volunteers her time with the Migrant Solidarity Mutual Aid Network, attended the meeting to speak on behalf of unpaid workers. After the meeting, she told DCist/WAMU: “My biggest takeaway was that the local governments are totally under water.”

Meanwhile, migrants continue to arrive in D.C. They trust the city to take care of them. “We traveled through the jungle and cities, we had to learn to trust,” says Ronald. “We didn’t have many options. So once you have been through so many difficult moments, suddenly you think that God put so many nice people in your path.”

Amanda Michelle Gomez

Amanda Michelle Gomez