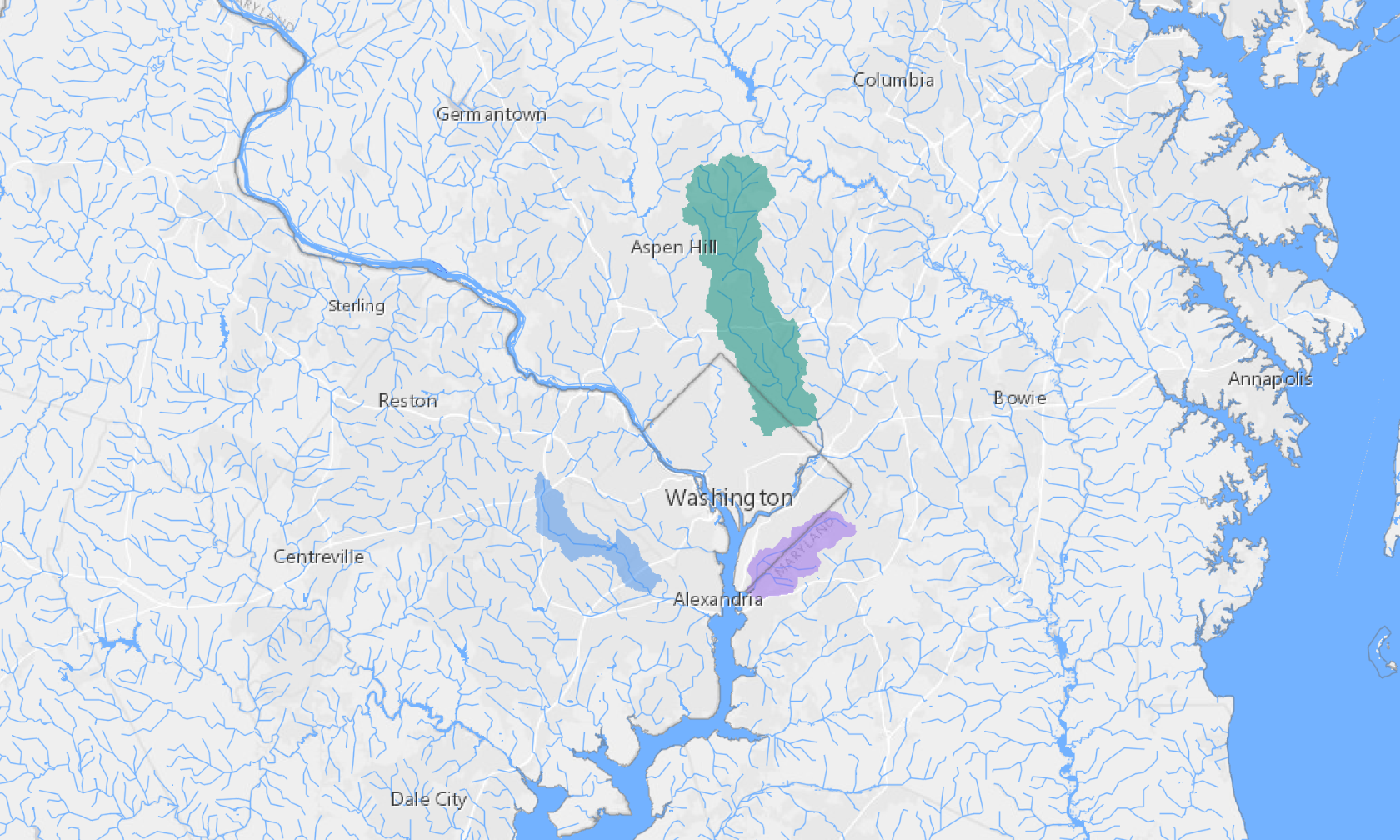

If you look at a hydrological map of the D.C. area, you’ll see a landscape that is criss-crossed by little streams, like veins in a body, endlessly churning water through our neighborhoods and parks toward the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

“This is a wet, wet, streamy kind of a region,” says Eliza Cava, director of conservation at the Audubon Naturalist Society. Streams, she says, “are truly the primary feature of our region’s geology.”

The environmental group recently released a report assessing the health of three small local streams. These creeks are miles apart from each other, in different states (and a district), and yet they share many of the same challenges.

“The little streams are the lifeblood of the bigger rivers,” says Cava. The Potomac and Anacostia rivers get a lot of attention, and billions of dollars are being spent to clean them up. But much of what ails the rivers begins upstream, in small creeks damaged by many decades of urbanization.

The streams featured in the report are Northwest Branch in Maryland, Oxon Run in D.C., and Holmes Run in Virginia. Northwest Branch and Holmes Run both receive a rating of “fair,” while Oxon Run scores “moderately poor.” Oxon Run lost points compared to the other streams due to its poor water quality and lack conserved natural areas.

The waterways were scored for 16 indicators across four categories: water quality, climate, access to nature, and biodiversity and habitat.

Northwest Branch is a tributary of the Anacostia River that starts in the rural exurbs of Montgomery County, near Olney. It meanders through some of the county’s most densely populated areas, including Silver Spring and Takoma Park, before entering Prince George’s County and joining with Northeast Branch in Bladensburg, forming the main stem of the Anacostia. Overall, it drains 52 square miles of mostly suburban land.

Holmes Run drains a watershed of 28 square miles in Fairfax County, emptying into Cameron Run and the Potomac River just south of Alexandria. While some of the watershed is made up of park land, the stream also receives polluted runoff from the Beltway, I-395, and Route 50.

Oxon Run has a watershed of 14 square miles, draining parts of D.C.’s Ward 7 and Ward 8, as well as part of Prince George’s County, and emptying into the Potomac River at Oxon Cove. Unlike the other two streams, much of Oxon Run is channelized, running through a large concrete ditch, which makes it less hospitable for aquatic life. Of the three streams studied, it is the most urbanized, with 35% of the watershed covered in pavement and other impervious surfaces. Research suggests that healthy streams need to have no more than 5% to 10% impervious surfaces in their watersheds.

The report was conducted with help from local government agencies, as well as friends groups that are helping to restore the three waterways.

“I’m hoping we come to a point in the city where we start valuing these natural resources,” says Absalom Jordan, chair of Friends of Oxon Run.

Jordan says the report will be useful to help educate people on the importance of stream health, but he doesn’t like seeing his waterway scoring on the bottom of the list.

“It hurts, I’ll be honest with you,” Jordan says. “If we were located in Ward 3, as opposed to being in Ward 8, – if we were in a predominantly white ward as opposed to a predominantly Black ward – I think the response to our needs would be different. I hate to say that, but that’s a reality.”

There is a major restoration project in the works for Oxon Run that will replace the concrete with a more natural landscape. The project is currently in the design phase, with construction slated to begin in 2027 or later.

Nora Swisher, president of the board of Neighbors of the Northwest Branch, says all three streams have a “visibility problem,” even though they run right through the middle of neighborhoods.

“Our streams are tucked away in parks. A lot of people go through their daily lives and don’t necessarily cross paths with them, even though they are such an important part of the ecosystem,” says Swisher.

The solutions to improving stream health range from things individuals can do to more systemic fixes, Cava says. But they all boil down to three basic things: “Less pavement, more trees and wetlands, and cleaner air,” Cava says.

Pavement and other impervious surfaces cause polluted runoff to flow into streams. In more natural, asphalt-free environments, water is sucked up by plant roots and is filtered through the ground, which helps clean it before it finds its way into a local stream. On impervious surfaces, stormwater can’t soak in, so streams quickly fill up with rushing, polluted water, causing erosion and destroying habitat.

Planting trees and restoring wetlands helps prevent erosion, and also provides habitat to wildlife. Cleaning up the air prevents airborne pollutants from contaminating waterways after settling on the land.

Residents who want to help their local streams can get involved by volunteering to remove invasive plants, planting trees and native plants on their property, replacing impervious driveways and patios with permeable alternatives, and installing rain barrels. But, Cava says, larger solutions are also needed, including limiting suburban sprawl and car reliance.

“We need people to speak up for the streams,” Cava says. “We need our elected officials to know that we care about them.”

Fixing the region’s small streams may seem like a daunting prospect, given that it could require changes to things as fundamental as how we get around and where we live.

But Whitney Redding, with Friends of Holmes Run, says positive change in these small waterways will have a big impact in the larger rivers they feed.

“Pay more attention to what goes into your local, inland, urbanized, channelized, or intermittent stream, and you will protect all the waterways and habitats downstream too,” says Redding. “Problems, yes, they can be inherited downstream, but then, so can solutions.”

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston