D.C.’s first standardized testing results since the pandemic began show what local school leaders had expected: a substantial decline in reading and math proficiency, and the widening of an already troubling achievement gap between white and non-white students.

Students in grades 3-12 took the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness For College and Careers (PARCC) and the Multi-State Alternate Assessment (MSAA) for the first time in two years this spring, after city education leaders paused standardized testing during the pandemic. For roughly half of the students assessed, it was their first time ever taking a standardized test. The results, released Friday by the Office of the State Superintendent, confirm the prevailing concern over the past two years of remote or otherwise complicated schooling — that students have fallen behind, and the city’s most at-risk children are those most impacted by the pandemic’s disruptions.

“The data reinforces our recovery and restoration work and the investments and it will drive the decisions that we make going forward,” said State Superintendent of Education Christina Grant, during a call with reporters. “We now have a clearer picture of where our students need the most help.”

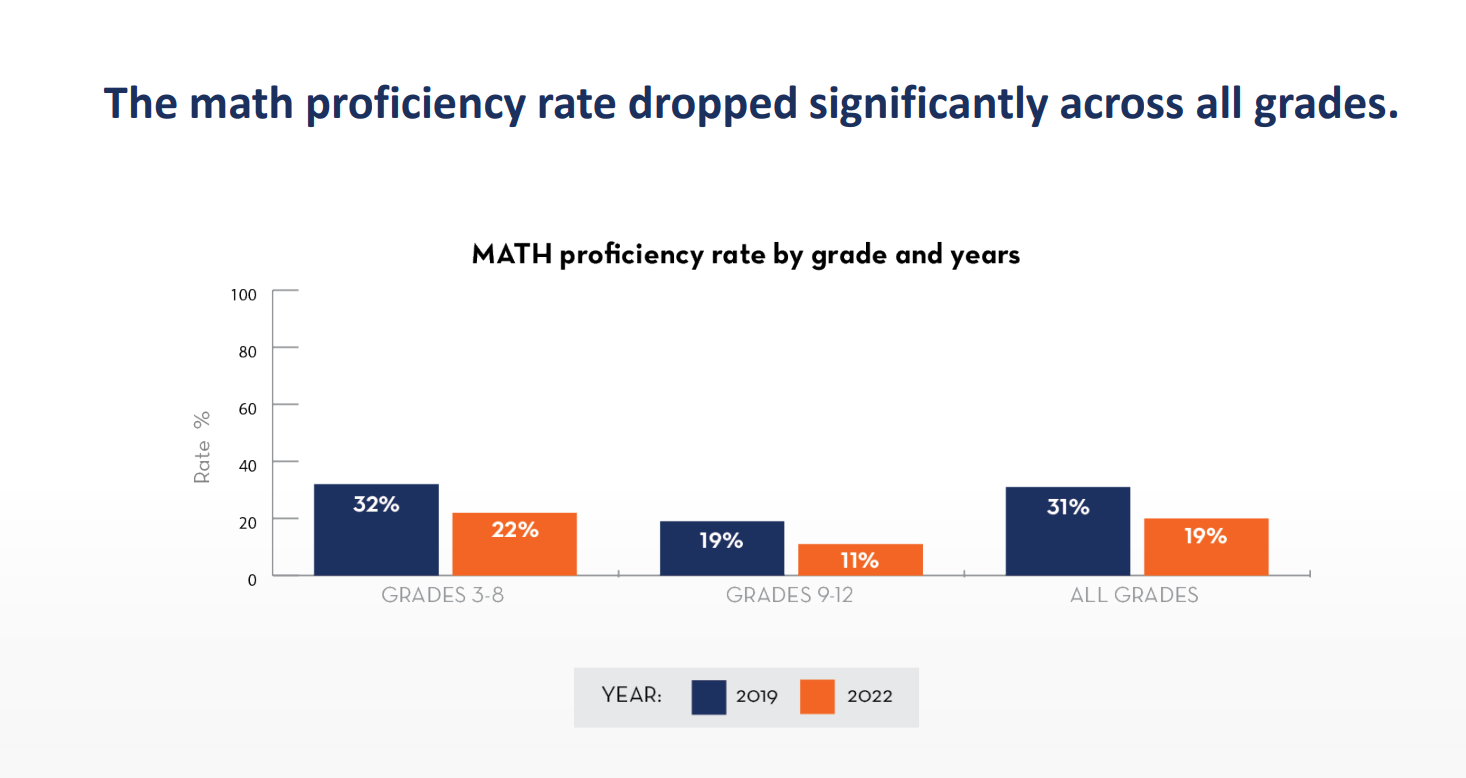

Across all grades, math proficiency rates plummeted. 60 percent of students scored level one or two on the PARCC assessment — a sizeable decrease from 2019. In the last batch of results, 31% of students scored proficient in math — meaning on or above grade level — compared to 19% this year, the lowest scores since the city first started administering the test in the 2014-2015 school year.

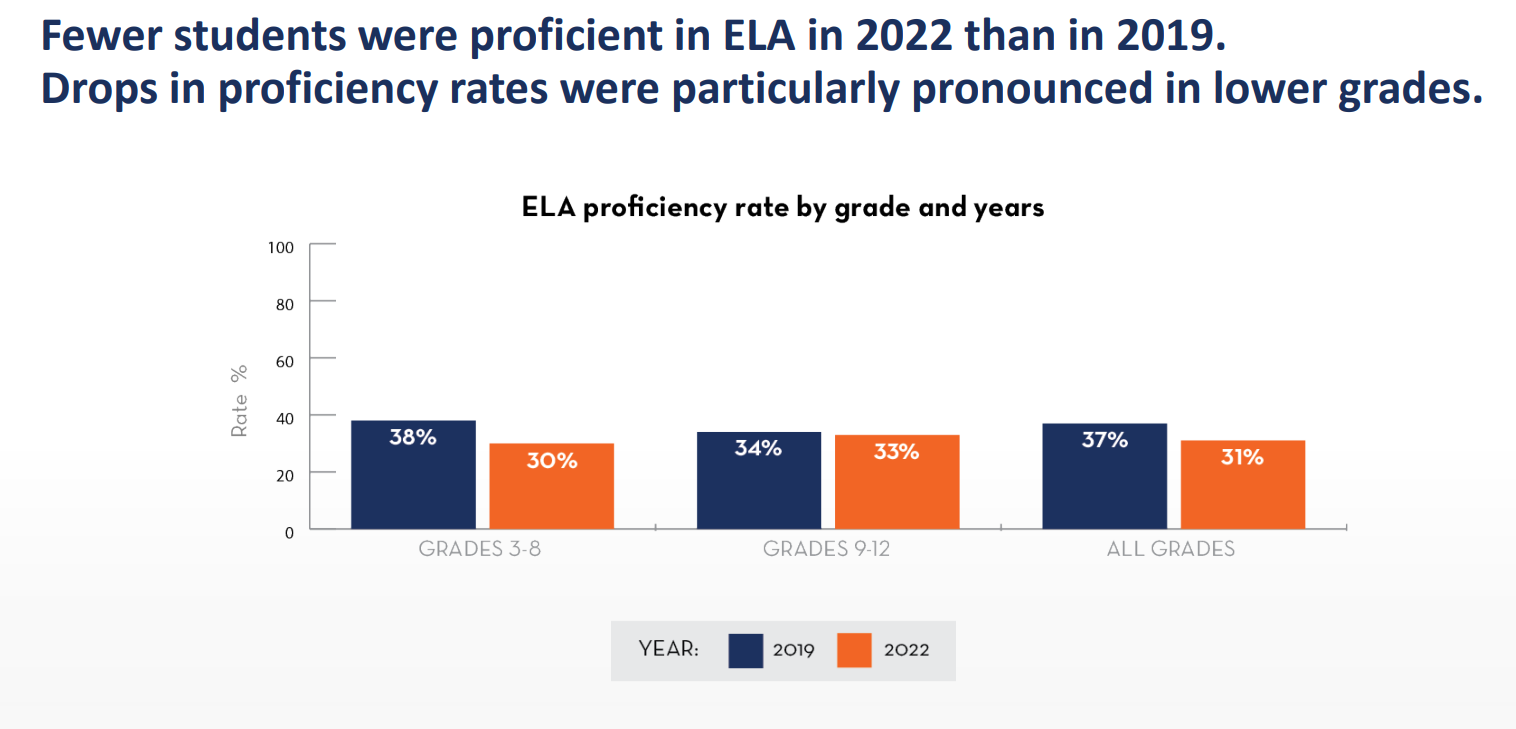

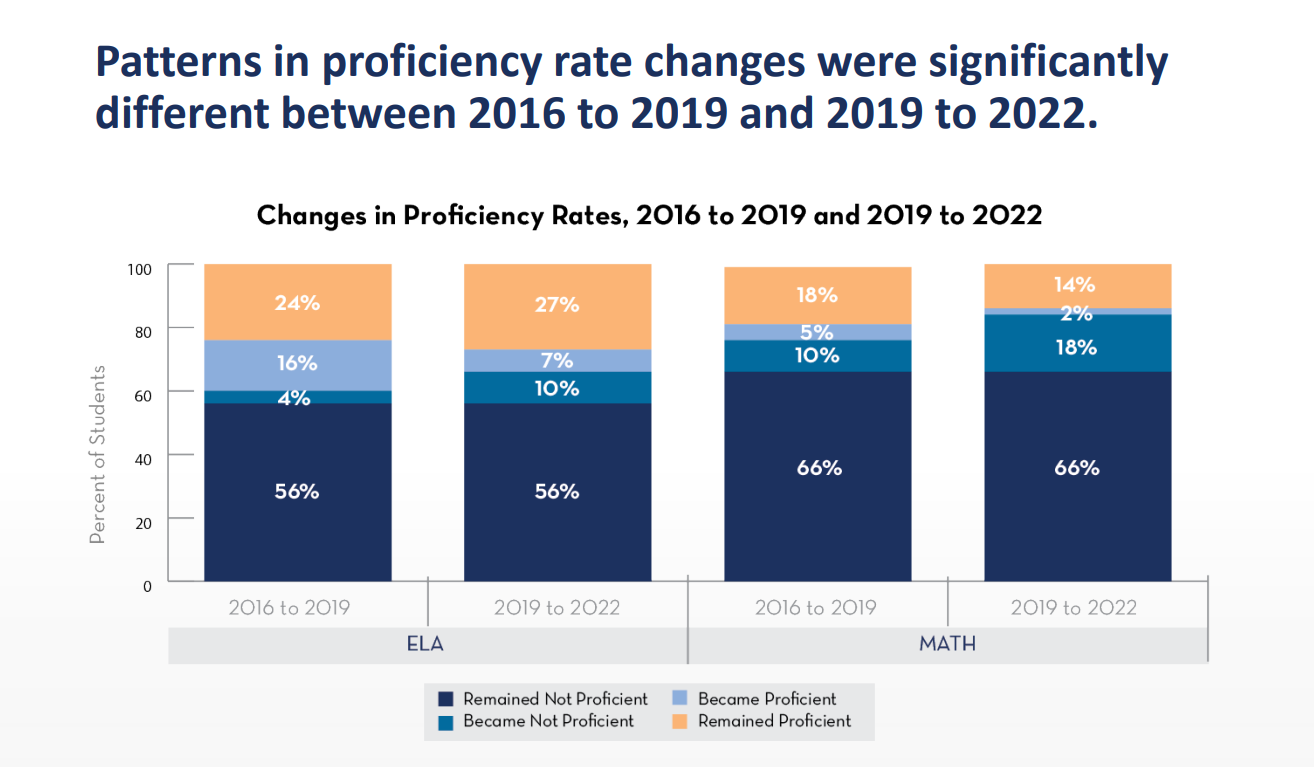

For reading scores, 37% of students were proficient in 2019, compared to 31% in 2022, with the largest learning loss occurring in younger students. The city also compared the change in proficiency rates from 2019 to 2022 to the rate of change from 2016 to 2019. Ten percent of students fell from proficient to not proficient from 2016 to 2019. That number grew to 18% from 2019 to 2022. In reading, 10% of students fell out of proficiency from 2019 to 2022, compared to 4% from 2016 to 2019.

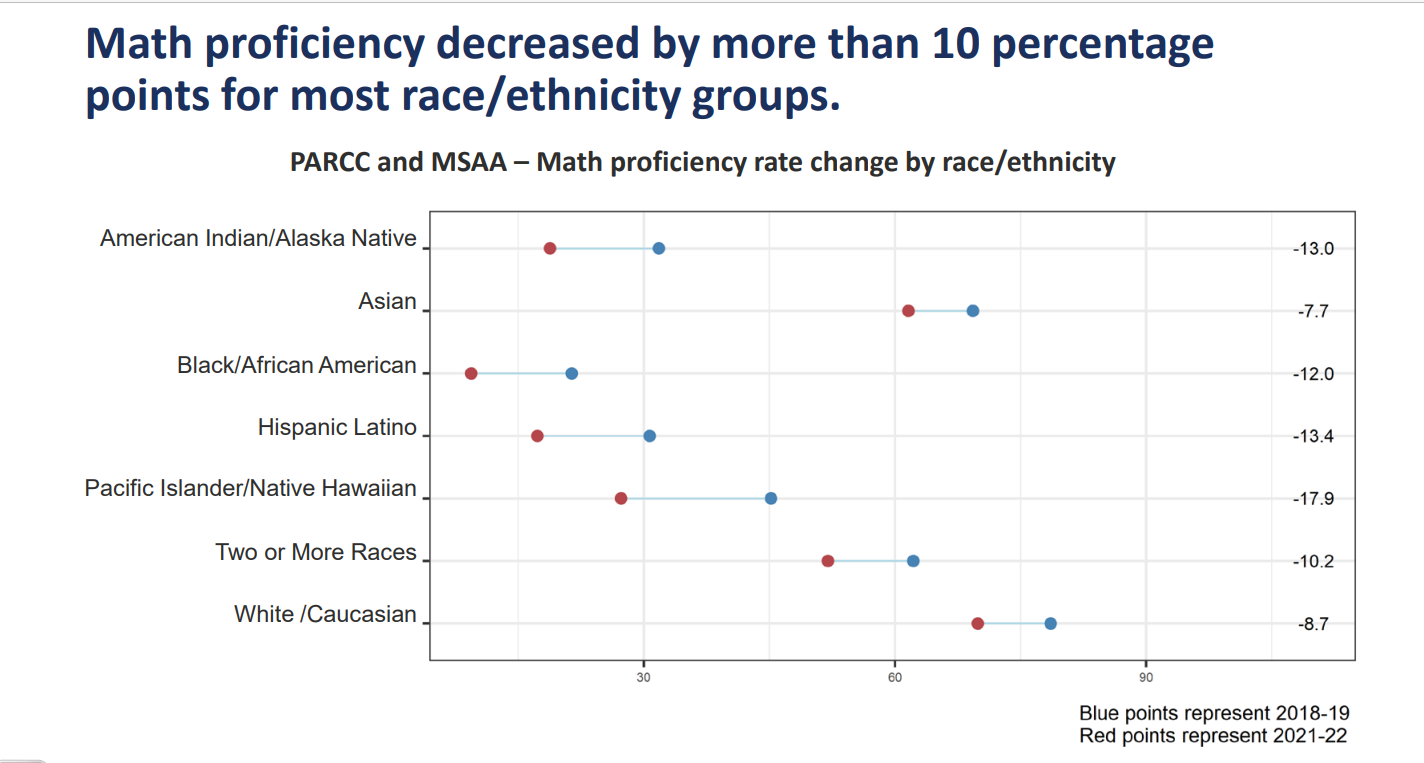

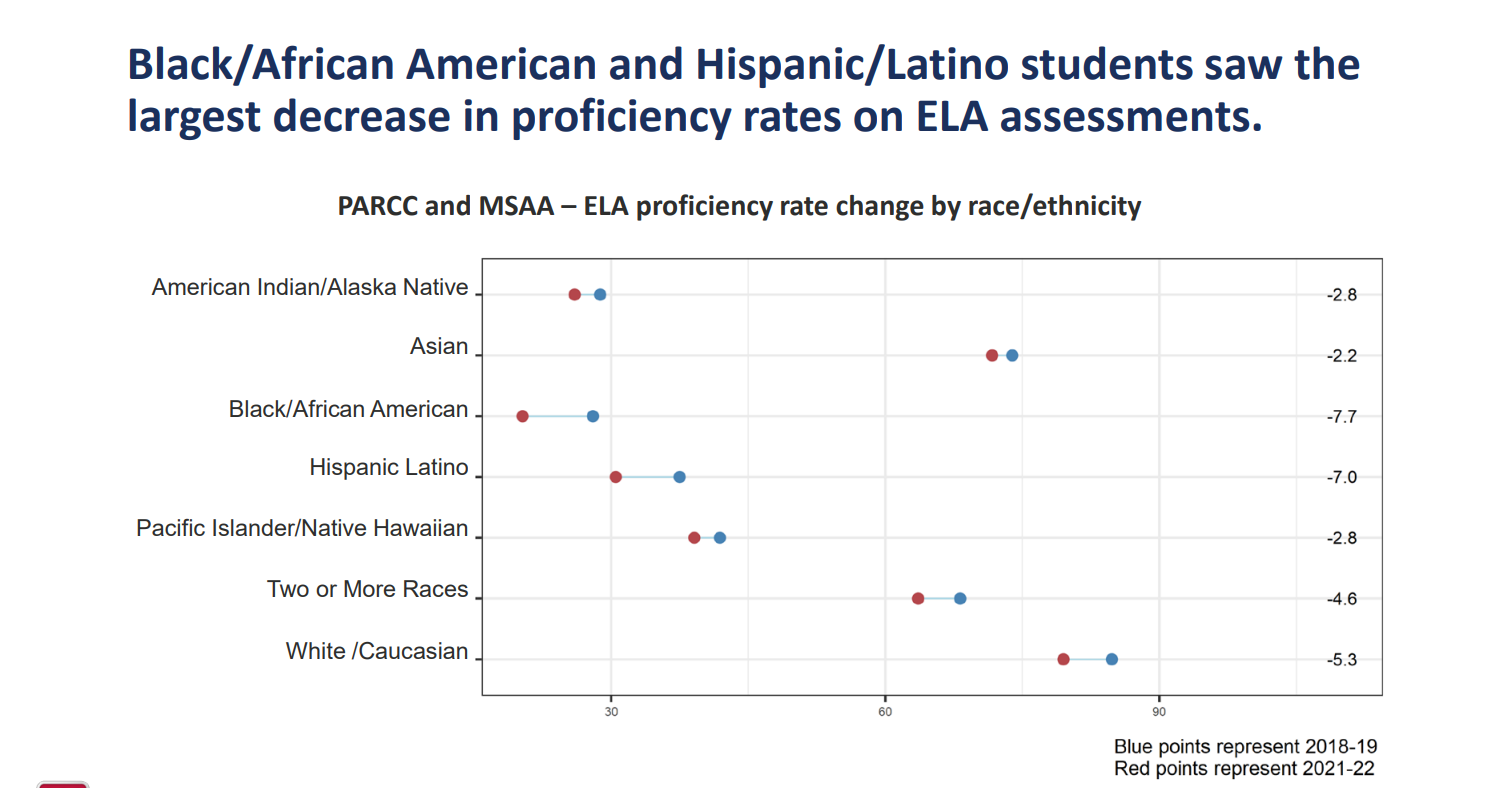

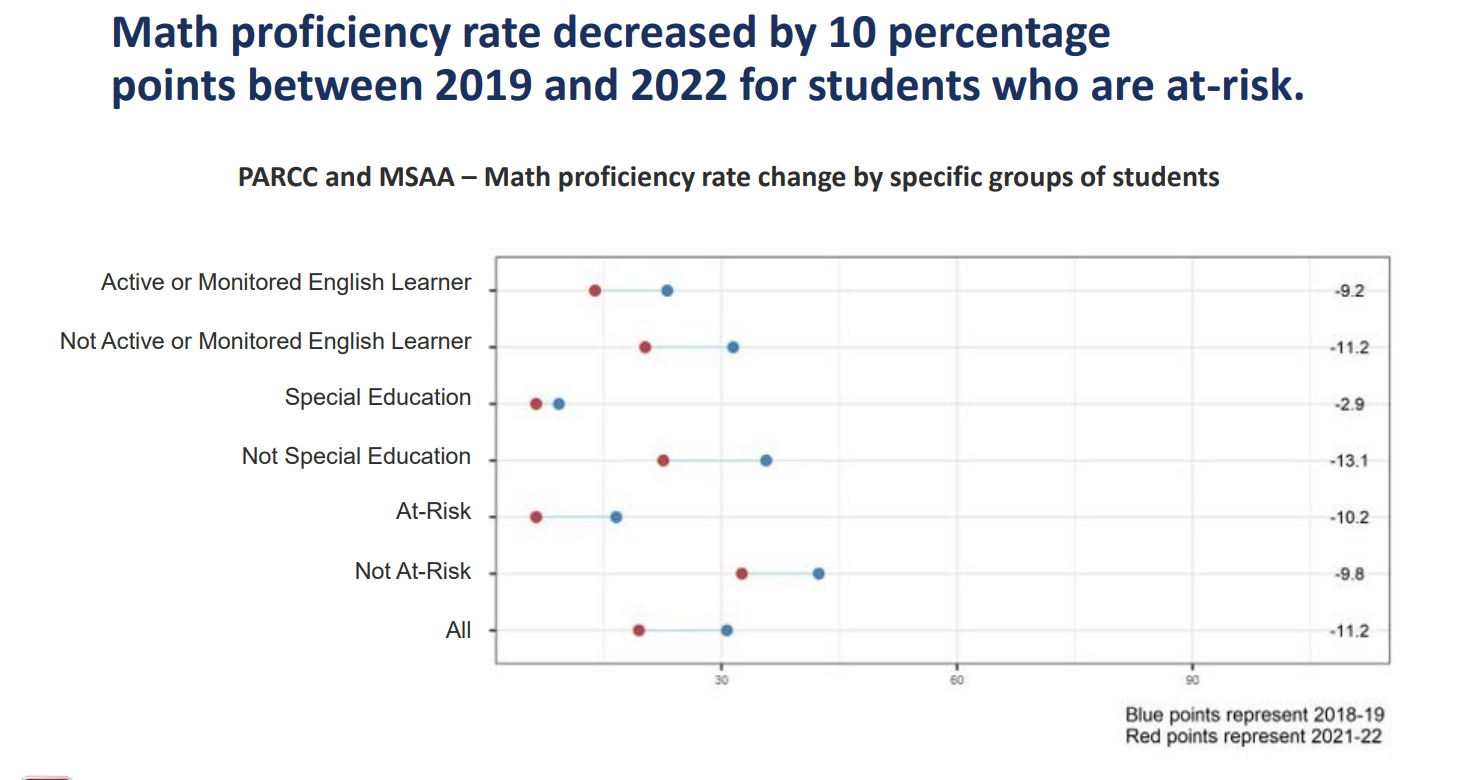

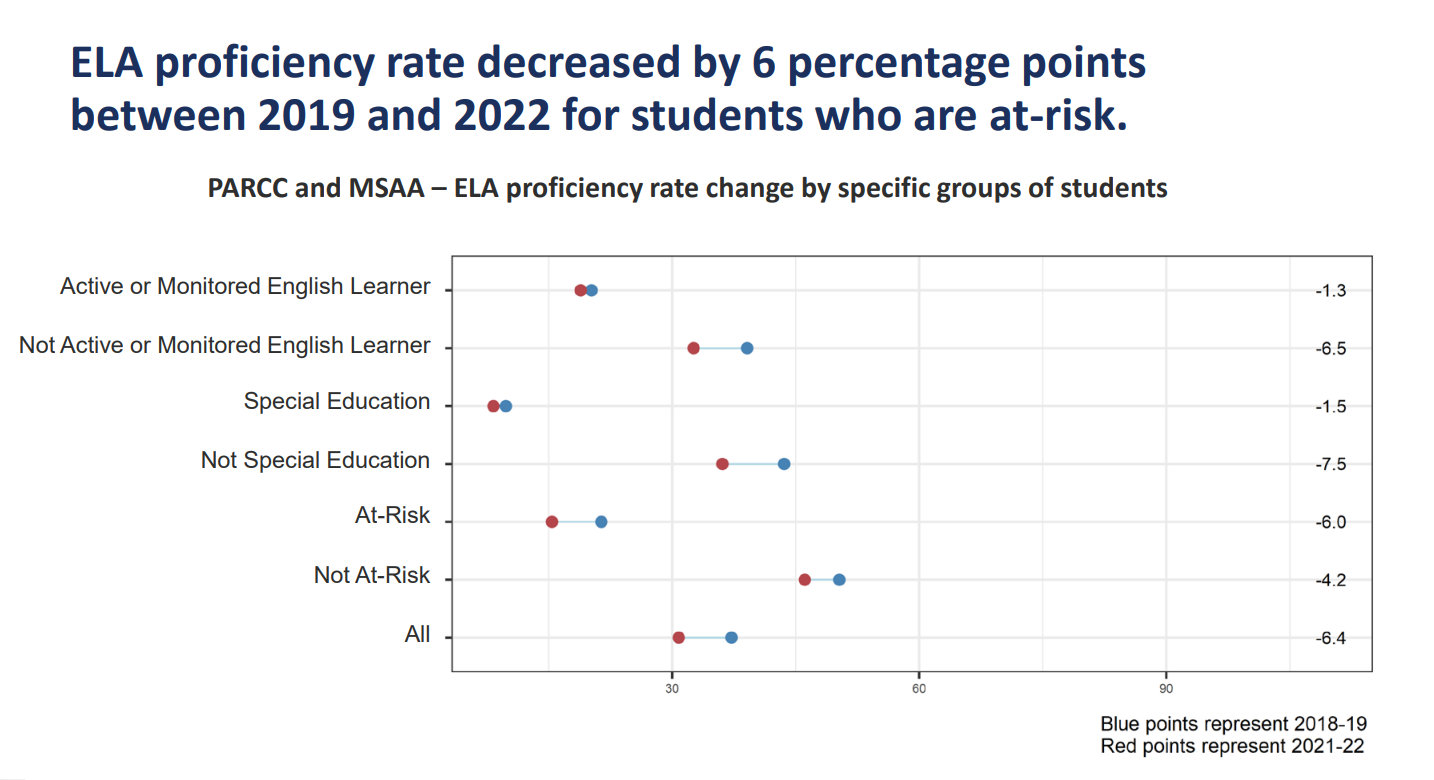

The results show that learning loss was most acute among the city’s low-income and non-white students — a fact proved by previous studies, and an outcome that mirrors most reverberations of the pandemic, where individuals already marginalized or at-risk bore the brunt of its impacts.

While reading proficiency dropped by roughly 5% for white students from 2019 to 2022, proficiency for Hispanic Latino students fell by 7%, and 7.7% for Black students. In math, proficiency rates dropped by 12% for Black students and 13% for Hispanic Latino students, compared to 8.7% for white students. For at-risk students — students who are experiencing homelessness, are in foster care, or qualify for SNAP or TANF — learning loss looked similar. At-risk students’ reading proficiency rates dropped by 6%, compared to 4.2% in not-at-risk students, and their math scores well by 10.2%. Not-at-risk students’ math proficiency fell by 9.8%

“We were prepared for this moment, we knew that our students had not been assessed for more than two years,” Grant said. “And we knew that the pandemic would have a profound impact on all of our students, especially so on our students who already(are) historically disadvantaged.”

D.C. Public Schools reopened for full in-person learning in the fall of 2021, after more than a year of remote learning. When schools transitioned online at the start of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, the school system struggled to fully equip all students with the necessary technology, and at-home schooling disadvantaged children who did not have ideal at-home learning set-ups. Students whose guardians or parents worked throughout the pandemic did not have the in-home support that a child whose parents worked remotely may have had, and for many students, the pandemic brought on additional responsibilities that superseded attending virtual class, like working a job or taking care of siblings and parents.

The 2021-2022 school year, while no longer fully remote, wasn’t clear of interruptions either. Instead it was marked by sporadic outbreaks, inconsistent quarantine guidelines, and in the winter, the massively disruptive rise of the omicron variant. As Grant noted in presenting the data to reporters, the social and emotional impacts of the past years hung over students into 2022, and needed to be factored in when discussing test results.

“While students were learning in person for the 2021-22 school year, they returned to the classroom facing significant mental health and social emotional challenges, which also impacted their learning.”

Local education officials including Grant, DCPS Chancellor Lewis Ferebee, and Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn said Thursday that the results, while predictable, give school leaders a blueprint for how to narrow the gaps — some which pre-dated the pandemic — that have been exacerbated by at-home learning. According to Ferebee, about 38% of DCPS students received some type of intervention in the 2021-2022 school year to improve their emotional, social, or academic progress.

The city is investing nearly $1 billion of federal pandemic stimulus funds in recouping students and schools from the impacts of the pandemic, creating multi-year programs with the money. Many of the strategies to catch students up have already been implemented, like a “high-dose” tutoring program, which occurs both outside and during school hours in small, specialized groups. In the coming 2023-2024 school year, OSSE plans to expand high-dose tutoring to 8,000 students, up from the current 4,000 currently being targeted. Officials are also creating new literacy training for educators to be better target the science of how students learn to read, in order to close the literacy gap especially in elementary-age students.

“We believe that the results represent our strong work, and we also know that this is an opportunity to go deeper, further faster with a greater sense of urgency,” Ferebee said.

This story has been corrected to reflect that 38% of DCPS students received an intervention in the 2021-2022 school year.

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick