You could call it the Paris Agreement of Virginia politics. Just as Donald Trump vowed to withdraw from that climate agreement as soon as possible upon taking office, arguing that international cooperation to avoid climate disaster was a strain on American taxpayers, so too has Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) pledged to pull out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, saying it’s a burden on state residents and businesses.

The initiative, known by the acronym RGGI (pronounced “Reggie”) is a cap and trade program, aiming to cut greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. In Virginia, proceeds from the program have totalled more than $370 million dollars since the state joined last year.

In D.C.’s Northern Virginia suburbs, that money has funded $10 million in climate resilience projects – things like putting in bigger stormwater pipes to prevent flooding, and retrofitting low-income residents’ homes to make them more energy efficient.

A New Roof Helped Him Keep His Home

Donald Dunnuck is one of the people who benefited from that funding. Dunnuck had a very leaky roof in his house in Franconia – so bad it took out big chunks of his ceiling.

“I literally had openings maybe two feet wide by six feet long,” Dunnuck says. “You can imagine the heating bills – I was heating the attic and everything else.”

Dunnuck has lived in the small house just about his whole life. His parents bought it in 1951 – decades before the Metro tracks in front of the house went in, and before the nearby Springfield Mall was built.

“This was all country, all woods,” he says, pointing from his large overgrown backyard to the massive houses he calls “the McMansions.”

“We used to play back there when we were kids.”

Recently, Dunnuck was on the verge of losing the house. With a leaky roof, no insulation, inefficient space heaters, his electric bills were almost $600 a month in the winter. That’s more than half his monthly income from social security and disability, Dunnuck says.

“Everybody told me, just sell,” Dunnuck says. “But I didn’t want to give up that easy.”

There’s federal funding to help low-income residents like Dunnuck make their homes more energy efficient. But until recently there was a big gap – the funding would pay for insulating your roof, for example, but not if your roof needed fixing first. But thanks to RGGI, there’s a new pool of money that pays for those fixes.

Dunnuck got a new roof, insulation, new windows, and a new heat pump through Community Housing Partners. The organization has completed more than 230 such projects in the past year and a half, using $1.2 million in RGGI proceeds, with 330 more households in the pipeline – another $1.5 million in RGGI-funded work.

‘A Bad Deal For Virginia’

Here’s how RGGI works: power companies have to buy allowances for every ton of carbon they emit. Over time, the number of allowances up for auction declines, incentivizing companies to cut emissions. In Virginia, the utility companies can turn around and bill their customers for the extra cost of paying to pollute – currently about $2.50 a month for the average Virginia household and $1,500 for the typical industrial customer. Under state law, half the proceeds from these allowance auctions go to energy efficiency upgrades for low-income residents, and half go to flood prevention projects.

In other words, the program attacks climate change from both sides: working to slash carbon emissions and slow down global warming, while at the same time generating funding to adapt to a warmer, wetter mid-Atlantic climate.

Many Republicans in Virginia, including the governor, see the initiative as an energy tax.

“The way RGGI has been implemented here in Virginia is what makes it a bad deal for Virginia,” says Travis Voyles, Virginia’s Acting Secretary of Natural Resources.

Youngkin has targeted RGGI since the campaign trail. He started the process of withdrawing in an executive order on inauguration day earlier this year, and recently laid out a plan to repeal the regulation that enables RGGI participation, pulling out by the end of 2023. Public comment on the repeal is open until Oct. 26.

Voyles says there are better ways to fund flood prevention and energy efficiency projects.

“If we want to support those programs, which we do – we support resiliency throughout Virginia – we can be transparent about that and we can fund those separately and directly and not have to do it through yet another burden on your tax bill.”

The administration also argues RGGI isn’t effective at cutting emissions: because power companies can pass on the cost to consumers, they’re not incentivized to change behavior.

‘A Long Track Record Of Emissions Reductions’

RGGI supporters say the cap and trade program works – and it’s needed to meet Virginia’s climate goals, which include a legal requirement that 100% of electricity come from renewable sources by 2050.

“We are not the first state to participate in RGGI – it’s been around over ten years and there’s a long track record of emissions reductions,” says Nate Benforado, senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

Ten other east coast states are part of the program, from Maine to Maryland. In RGGI’s first decade, before Virginia joined, emissions from power plants in those states dropped by 50% – twice as fast as in the rest of the country.

As for the resilience funding, which the Youngkin administration says can come from somewhere else, Benforado is skeptical. “The administration has not proposed any actual replacement funding for these important programs,” he says.

But Voyles insists the administration is committed to the resilience programs.

“There’s a lot of money out there already on resiliency that we can tap into as a state, and technical assistance and expertise that we can provide,” he says.

Additionally, Voyles says that in the next legislative session, the governor plans to look at “what the appropriate role is for Virginia as a state government in terms of funding these programs.”

Local Impact In Northern Virginia And Beyond

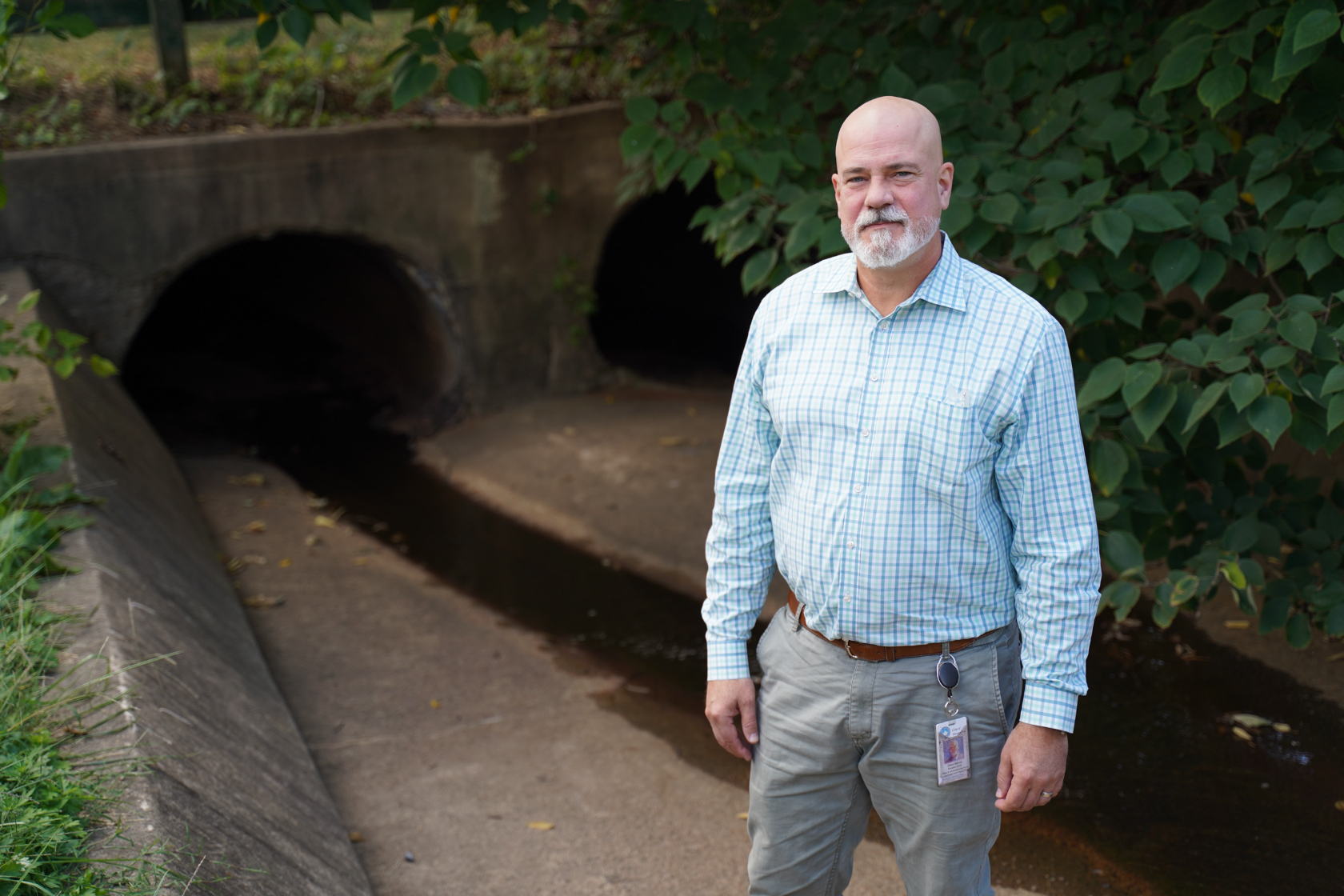

Alexandria’s Arlandria neighborhood is a lively, diverse mix of old row houses and apartment buildings near Four Mile Run. In the past few years, the neighborhood has flooded frequently – water rushing through the streets, people’s basements, and first floor apartments. There were major flash floods in the area in July 2019, July 2020, Sept. 2020, and Aug. 2021, says Jesse Maines, chief of the city’s Stormwater Management Division

“Storms that we’ve called 100 year storms, we’re seeing every year,” Maines says. Climate change has already created a “new normal,” he says, with intense storms overwhelming old drainage systems.

The city of Alexandria is the biggest recipient of RGGI flood prevention funding in Northern Virginia so far, bringing in $6 million for projects in flood-prone neighborhoods. This includes a redesign of the Old Town waterfront to protect the historic neighborhood from sea-level rise.

In Arlandria, the plan is to replace some of the old drainage pipes with new ones that are twice as wide, and put in new culverts to quickly carry runoff to the nearby creek so it doesn’t back up in the streets.

“We need new infrastructure. We need new pipes. We need bigger pipes. We need more inlets to convey this water off these areas,” Maines says.

The City of Fairfax has also been awarded $150,000 in RGGI flood prevention dollars, to be used on resilience planning and a floodplain improvement study. The Northern Virginia Regional Commission has gotten $80,000 for two flood-risk studies.

While the money is helpful in Northern Virginia, it can be critical in rural parts of the state. Alexandria, for example, would still conduct the stormwater projects even without RGGI money, Maines says, but can do them on a faster timeline with the funds.

In rural counties, some of which are extremely at risk from flooding, there may not be any other funding for resilience work, says Skip Styles, executive director of the nonprofit Wetland Watch.

“They don’t have people who are used to dealing with federal grants,” Styles says.

There’s one county where the staff is so small, Styles says, that the county floodplain manager has to check bear traps on the way into work. “He’s also the animal control officer,” Styles says.

The need for such funding in rural areas was highlighted this summer, when devastating floods hit the state’s southwestern corner, inundating Buchanan County.

A major storm hit even as the county was submitting its proposal for funding, in August 2021. “Swift-water rescues were performed, 20 houses were knocked from their foundations, and some children who had already gone to school for the day could not return to their homes,” reads the funding proposal.

The county was recently awarded $390,000 in RGGI funds to hire engineers to create “an actionable resilience plan” and to train a county staff member as a certified floodplain manager.

Making Affordable Housing More Efficient

The RGGI funding for affordable and low-income housing feeds into two different programs: one to fix up homes so they can be weatherized, and another to pay for efficiency upgrades in new housing developments or renovations.

The Arlington Partnership for Affordable Housing is renovating 163 affordable rental units in Arlington with the funding, and building 80 new affordable senior housing units in Fairfax County, using $3 million in RGGI funding.

APAH’s Garrett Jackson says that means residents will pay less on energy bills, with more in their pockets to spend on daily needs.

“Whether it’s household items, whether education, whether it’s enrichment programming for their children.”

Thanks to RGGI money, the homes will be 30% more energy efficient, Jackson says.

The future of RGGI in Virginia is still uncertain. Democrats say Governor Youngkin doesn’t have the authority to pull out without the General Assembly signing off, as lawmakers passed legislation to join the initiative. But Youngkin says he can do it on his own, through regulation – arguing that the legislation authorizes, but does not mandate RGGI participation.

Donald Dunnuck, who got to stay in his family home thanks to repairs made possible by RGGI funding, says the program shouldn’t be caught up in politics.

“A lot of people kind of look at these programs as a handout,” he says. “Really it’s not. It saves energy, it allowed me to keep my home, and it puts people to work.”

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston