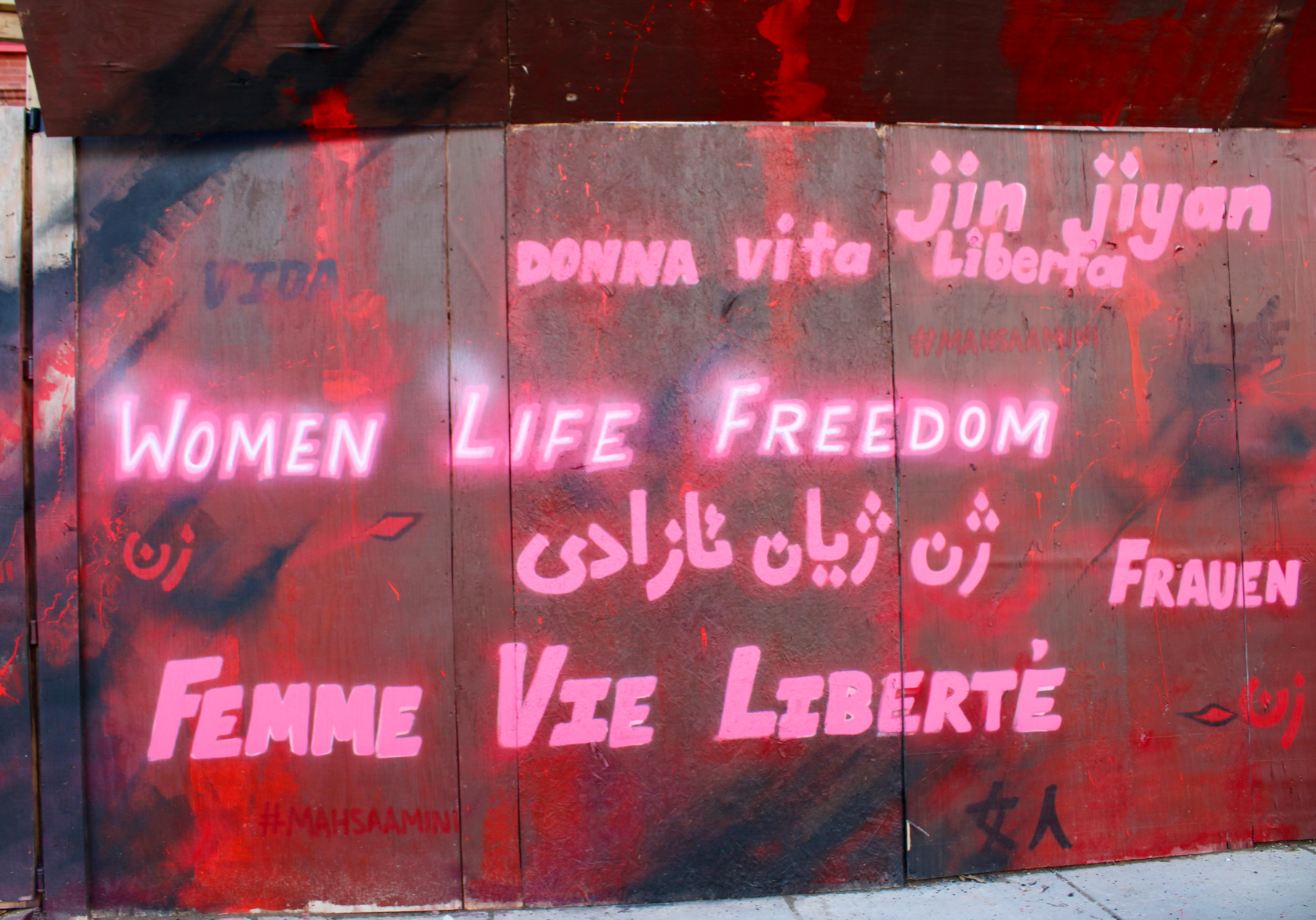

For almost three months, members of the Iranian diaspora have gathered regularly for rallies and demonstrations throughout the D.C. region. The movement began roughly one week after reports that Mahsi Amini – a 22 year-old woman who was arrested for allegedly not wearing her hijab properly – died while in police custody on Sept. 16, 2022. Her death, which many have blamed on Iran’s “morality police,” became a tipping point for Iranians throughout the world who are now calling for a revolution in the name of gender equality and freedom.

In D.C., a collective known as the National Solidarity Group of Iran has become part of the wave of people standing in solidarity with other Iranians by raising awareness, and showcasing their own stories of injustice. They’ve held small demonstrations in Reston, Va, and Rockville, Md, to try to keep the struggles of Iranians in the purview of local residents – but they’ve also brought thousands of people from beyond the region to rallies at the National Mall. Among those who have been coming almost every week is Halleh Seyson, a senior business and tech executive who has gotten involved in her spare time.

“Activism has been a routine thing for a lot of Iranians,” says Seyson, who lives near Logan Circle. “Now the lines of the diaspora and Iranians inside has broken. And actually, that’s also part of the reason why we go to rallies, to show Iranians inside that we are here to support you.”

Like other Iranians who were forced to flee the country, Seyson’s story is one of persecution and hardship. She has a Baháʼí background, which is a religion that was founded in 19th century Iran, but of which many practitioners have faced discrimination. Growing up, she says she was treated as a second class citizen.

“They started with religious apartheid in my case,” says Seyson. “So because I was part of a minority that was persecuted, I was deprived from a lot of rights, you know, civic rights as a citizen.”

In the late 1980s, Seyson says she began a remote correspondence with a university in the United States, but after some time, her homework stopped arriving in the mail. It turned out, she recalls, that it was being confiscated by authorities.

“No Baha’i could go to college after high school or no Baha’i could leave the country,” says Seyson.

After years of trying to get permission to travel, Seyson says she was able to flee in 1996 to Austria before arriving at Dulles Airport as a refugee. In her time since leaving Iran, Seyson hasn’t really looked back. That’s mostly because she was eager to leave it behind in hopes of a better future.

“Iran as a home was not there, did not exist for me,” says Seyson.

While she has found joy in the United States – with a successful career and a husband – she says the death of Amini and the protests that followed changed her perspective. According to Seyson, it made her realize that she had just as much a right to call Iran her home.

“I cannot stay silent when I see now everyone is suffering,” says Seyson. “I think we all are reclaiming the country and the identity that was essentially overtaken.”

Siamak Aram says he too wants to take back his country. As one of the key organizers for the NSGI, Aram says the movement is not about him or any one individual but rather a people who are fed up with what he calls a regime. Under the current leadership of Iran, Aram says that many are unable to openly express themselves and are forced to live a life in the shadows.

“This regime is not possible to be [reformed],” says Aram, 41, who lives in Prince George’s County. “We are done with this regime and we [want] to end it.”

Seyson says that it’s not just women who are arrested and punished, it can be anyone who the leadership takes fault with. And Aram says he has been arrested more times than he can remember for offenses like going on dates, or wearing the wrong haircut. In one instance, Aram and his family members were arrested for holding a birthday party in a basement – allegedly drinking and dancing to the likes of Michael Jackson, his favorite musician. Aram’s punishment, he says, was 40 floggings plus an additional four out of spite.

“If you haven’t, for example, gotten any lashes in your life, you’re not Iranian,” jokes Aram ironically. “That’s the reality.”

Since the protests began in late September, the Iranian government has reportedly cracked down on internal dissenters. Some have even been executed. Still, for Aram and Seyson, it’s important to distinguish between what they call a regime versus the everyday people of Iran. Mariam Afhsar, another organizer with the NSGI, says the movement is not really about the hijab or Islam but pushing back on an authoritarian government.

“We call it a revolution,” says Afshar, 22. “But what you see coming out of Iran, it’s not death to Islam or hating Islam, they just want freedom. They don’t want this regime forcing anything upon them… And what we’re fighting for here in D.C. is exactly that.”

Unlike Seyson and Aram, Afshar was not born in Iran. She’s an Iranian-American who was raised in northern Virginia. According to Afshar, her grandfather worked for the Shah of Iran, who went into exile on Jan. 16, 1979. Soon after, the country voted in a national referendum to make Iran the Islamic republic under which the current leadership continues to operate. It wasn’t long before her father made his way to the D.C. region.

For people like Behrous Davani, that history is important for non-Iranians in the D.C. region to understand why the protests are happening. What’s more, he wants people to know that the last four decades have not been easy. He was part of a wave of people who fled the country in the wake of the last revolution with the hopes of a more prosperous life.

“The whole situation changed dramatically,” says Davani, 61. “The life of a lot of people were impacted in many ways. Some people were executed. Some people were tortured. Some people ended up in jail.”

Davani has gone on to work for the National Cancer Institute, where he currently serves as the chief for its diversity training branch. As part of the older generation of the Iranian diaspora, Davani says it’s inspiring to see people speaking out against the leadership, either through music or action. Davani is especially moved by the work of young people like Afshar, who give him the hope of a better future within arms reach.

“Young generation have shown courage to come to the streets and demand for more freedom,” says Davani.

Afshar says her father was forced to leave Iran in the late 1970s to avoid persecution. He hasn’t returned since then and has long abandoned the possibility. As a result, Afshar herself has never set foot in Iran. But over the course of nearly four months, she says the participants in the demonstrations have given her a greater sense of community.

“Even though I’ve never been to Iran, they brought a piece of Iran here to me,” says Afshar.

While the United Nations recently removed Iran from the commission on the Status of Women, in addition to Iran stating that it has disbanded the “morality police”, activists want more action taken against the country’s top level officials – including sanctions and legislative measures.

Organizers say they also want to see more support from elected officials both nationally and on the local level. In December, members of the NSGI rallied at the Wilson Building to ask Mayor Muriel Bowser and the D.C. Council to support their cause. Ellie Sepehri, a pediatrician in D.C., has even sent letters to officials like David Trone, who represents Maryland’s 6th Congressional District – which includes parts of Montgomery County.

“My biggest motivation, honestly, is to send a message to family and friends back home that we haven’t forgotten you,” says Sepehri, 37, a first-generation Iranian-American who lives in Gaithersburg.

For Afshar, there is an obligation to call on the world to pay attention to what’s happening in Iran. She believes her revolution is something she owes to the people – even if it does take years to hold. While she and her father might not ever have a chance at a homecoming, she can’t help but to dream of its possibility.

“If I am here and they’re free, that’s more than enough for me,” she continues. “But I do wish and hope that one day – not only for me, but for my father as well – to go back and see Iran in all its beauty and in all its glory and its freedom.”

On Sunday, Jan. 8, the NSGI will hold its 14th rally at 2 p.m. at the Lincoln Memorial. The group is expecting a large crowd – many of whom will be local to D.C., Maryland, and Virginia – and it will march to the Embassy of Pakistan, which houses the Interests Section of Islamic Republic of Iran.

Héctor Alejandro Arzate

Héctor Alejandro Arzate