This story was produced by El Tiempo Latino. La puedes leer en español aquí.

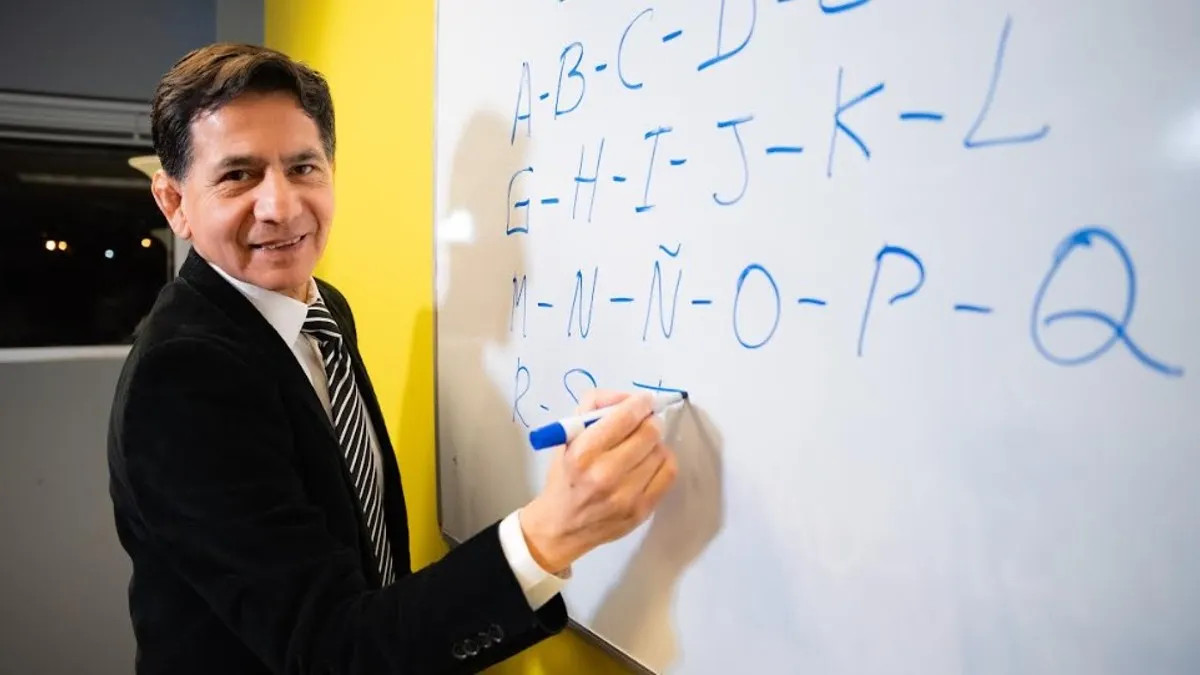

When Mario Gamboa arrived in the United States, he did not know that three months later his mission would be to help hundreds of Latinos come out of the illiteracy tunnel. He, a Peruvian soldier with a background in software engineering, just wanted to work and start a small business.

So he did.

After working as a gardener and house painter, he created a gardening and painting business. That is what he was doing until two of his workers failed to do the tasks he had written down on a piece of paper. They did not know how to read and write.

From that day on, he transformed the basement where he lived into a classroom for Carlos and Ronald. And soon, six more students arrived. Seven years later, the demand for teaching the alphabet and syllabaries increased so much that Cenaes, a nonprofit organization, was created in 2010. With the support of around 20 volunteer teachers, nearly 1,200 immigrants now know how to use and make sense of the ABCs.

The origin of the students has not changed much since the beginning. They continue to be mostly women from El Salvador and Guatemala. Recently, the organization Tepeyac is also seeing an influx of new immigrants from Mexico and a pressing need to offer them Spanish classes. “We are in talks with [Tepeyac] to see if we can install a classroom on their premises,” Gamboa says.

A lot of desire, a notebook, a pencil, and an eraser. That, in order of priority, is the list of school supplies for an adult who wants to learn to read and write in Spanish. In the United States, no other organization besides Cenaes is known to be dedicated to this mission full-time. Prior to the pandemic, Gamboa was in talks to implement Cenaes in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Texas.

“It’s just a dream, but how nice it would be for all Latinos who only see the alphabet as a soup of single letters to become literate. At least in the metropolitan area we have an experienced organization,” says Gamboa.

After interviewing the majority of Latin American ambassadors, Gamboa estimates there are around 50,000 Latinos in the D.C. region who do not know how to read and write in Spanish with moderate fluency. With the influx of more immigrants from Guatemala and other Central American nations, there is likely to be more need for literacy training. In the broader population, a 2020 report by the Washington Literacy Center found that one in four adults in D.C. struggle with basic reading.

New classes in Maryland and D.C.

“We are in a moment of expansion. We have several requests from organizations to carry out the literacy program,” Gamboa says. Two classes will open this semester at High Point High School in Beltsville and Wheaton Methodist Church in Maryland.

Cenaes will also open a Spanish class at the Latin American Youth Center (LAYC) in D.C. and have an office at the center for planning and meeting with volunteer teachers. “Illiterate youth are coming from Central America and Patricia Bravo, director of operations [at LAYC], wants to support these kids,” says Gamboa.

Another new project Cenaes is looking to cement is teaching classes for the children of parents who are learning to read and write in Spanish. This experimental idea arose from adults’ constant complaints that they do not understand their children because they only speak English. Parents do not know how to help them because they barely recognize the letters of the alphabet. To pilot this model, they have eight students between the ages of 6 and 13 in a classroom in Virginia.

Gamboa recognizes that teaching a language is different for children. “We are trained and experienced in adult literacy. For children you need pedagogy, teaching materials, teachers, and different classrooms. We are looking at how we can address these needs.” The goal two years from now is to have the right structure, he says, because church halls or the dining room in a senior center are fine for adults, but not for the little ones.

It all started 19 years ago

“Nineteen years ago, I took the literacy classroom out of my home and opened it at LAYC. Nineteen years later, I’m returning to the same place, but I am no longer alone as I was then,” says Gamboa. “Now we are a legally accredited organization. We have volunteer teachers, nine classes set up in different locations, with three or four more to be opened, and a budget of $50,000, which is very little, but when I started, there was no blackboard to write on and no chairs to sit on.”

For the reach of its program, Cenaes is underfunded. Gamboa feels that illiterate people are not a priority. “I understand that the main thing is to learn English, but if there is a group that has no idea of their native language and we don’t give them the opportunity to break those limitations, it will be more difficult for them to integrate into this society.”

The organization’s primary expenses are its office, which is required by law, plus stipends and transportation for volunteers and coordinators from Maryland, D.C., and Virginia. Funds also go toward classroom materials and educational kits, and the accountant who helps keep their records in order and presents them to the government. Every Christmas, thanks to donations, a dinner is given and toys are distributed to 150 of the students’ children. For students, classes are free of charge.

Enrollment and a new semester

During the pandemic, online classes were held, which was a nearly insurmountable challenge. But thanks to the tenacity of the volunteers and the deep desire of the students to learn, the program was not suspended. “We lost several volunteers and students in that time, but now we are recovering,” Gamboa says. “In October, we started with 60 students, and today we have 98.” There is still a lack of volunteers; several of them did not return after the health emergency due to economic conditions. January was a month of enrollment and the beginning of the semester. Gamboa estimates that by June, Cenaes will have 150 to 200 students in the classroom.

Those are the short-term expectations for a man whose career in the United States has taken him in unexpected directions. He has a small business as planned, and the rest of his time is spent helping others shed their shame and poor self-esteem — some of the painful after-effects of not being able to read and write.

“I am not doing this alone,” Gamboa says. “There are volunteer teachers, organizations that lend us classrooms, and donors. The students say that Cenaes changed their lives, but the truth is that they have changed mine.”

Olga Imbaquingo

Olga Imbaquingo