After several years of declining infections, a new report illuminates how the pandemic has impaired the city’s efforts to eliminate HIV/AIDS, and widened the already existing disparities between Black and white patients.

According to the city’s HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STI, and TB Administration (HAHSTA) report, 2021 saw 230 new HIV diagnoses — a slight increase from 219 recorded the year before. The volume of HIV tests conducted fell by 20% during the same time period. Since 2019, the city has seen a 32% reduction in testing – underscoring COVID-19’s impact on preventative and diagnostic care.

“The presented data for 2020 and 2021 should be interpreted cautiously given the ongoing interruption in preventive health services that was experienced, both here and across the country,” reads the report. “Over the course of the pandemic, restricted patient eligibility for services, reduced operating hours, and suspended activities by provider facilities and organizations contributed to significant disruptions within the healthcare system, the effects of which are still being felt today.”

Speaking at an event for National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, Clover Barnes, DC Health’s senior deputy director of HAHSTA said next year’s numbers are expected to increase again.

“We’re not surprised to see that slight increase [in cases], as care seeking behaviors returned to normal,” Barnes said. “We do expect to see more increases in HIV as more people get tested. And return to their normal care seeking behavior.”

The report, an annual compilation of data on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also shows that fewer people who get diagnosed with HIV are getting connected to care. While in 2020, 83% of newly infected residents were linked to care within 30 days of a diagnosis, by 2021, that metric had fallen to 72%. The number of individuals reaching viral suppression – meaning they have achieved less than 200 copies of HIV material per milliliter of blood – also declined, from 73% in 2020 to 65% in 2021. Viral suppression is important to reducing likelihood of transmission.

“It’s a great example of how two different health issues can play off each other and exacerbate each other,” said Vanessa Batters-Thompson, the executive director of DC Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, a non-profit that oversees implementation of public policy in the city.

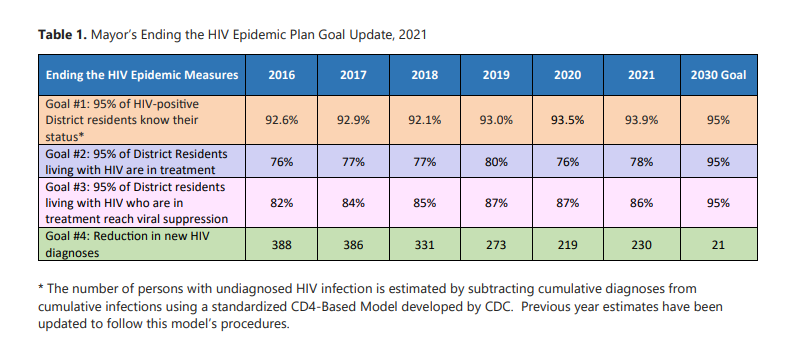

According to Batters-Thompson, the report casts doubt on the city’s ability to achieve the goals established by D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser in 2020. In unveiling a new strategic plan to end HIV, she set a 2030 target of 95% of people knowing their HIV status, 95% of people diagnosed with HIV being in treatment, and 95% of people in treatment reaching viral suppression. The city is also aiming to lower the yearly number of new diagnoses to 130 by 2030.

“We are not currently on track to meet those goals,” Batters-Thompson said. “Rather than moving in a positive direction towards hitting 95% by 2030, we actually took a step back. We need to think long and hard about how we reverse the pandemic trends and re-prioritize our work to ensure even people who face barriers to treatment can access it and can be as healthy as they possibly can be.”

As is the case across numerous pandemic-related outcomes, already marginalized communities bear the brunt of COVID-19’s impact. Black residents made up 71% of D.C. residents living with HIV in 2021, despite making up roughly 46% of D.C.’s population, according to the report. That’s up from 68% in 2020. The disparities are even wider when it comes to Black women; eight in 10 women diagnosed with HIV in 2021 were Black women, and between 2017 and 2021, one in five new HIV cases were in women of color.

“We know that with the HIV epidemic we have come so far, and yet all of us here are acutely aware that we must do more to realize the end of new HIV infections, particularly in our most affected communities, like the Black community,” said Harold Phillips, the director of the White House’s Office of National AIDS Policy on Tuesday.

During the event for National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, local and federal leaders emphasized the progress the District has made in the past 18 years in reducing HIV/AIDS rates, expanding testing, and expanding treatment. Officials said on Tuesday the city has successfully moved from a high incidence jurisdiction – meaning it had one of the highest rates in the country – to a moderate instance jurisdiction.”

“It means we need to continue what we’re doing.” Barnes of DC Health said. “It also means that we need to continue what we’re doing as a foundation and then build on top of that and have innovative programs that work to reach the people who haven’t been reached yet and who are still acquiring HIV.”

In 2005 D.C. reported the highest annual rate of reported AIDS cases out of any state in the U.S. A scathing report from the D.C. Appleseed Center for Law and Justice revealed at least one in 20 city residents were infected with HIV, and city officials were admonished for their failure in handling a deadly crisis.

But over the years, the city did make strides, ultimately becoming somewhat of a national exemplar. By 2015, the rate of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV had fallen by 57% since 2007, and the city saw an 80% reduction in intravenous drug-use transmission. In the second half of the 2000s, the city widely expanded testing availability – offering the service at the Department of Motor Vehicles, at social services centers, and through mobile vans that brought testing to night clubs and community events — and implemented a needle exchange program. The city also successfully eliminated perinatal transmission of HIV, or transmission from a parent to a child, and last year, DC Health implemented a pilot transitional housing program for men who have sex with men between the ages of 25-36.It’s meant to connect them with case management and PrEP, the preventative medication for HIV.

But advocates say more needs to be done on a broader policy level.

“In many ways, we’re a model city when it comes to thinking about policy changes,” said Dr. Maranda Ward, a professor at George Washington University School of Medicine and director of equity in the Department of Clinical Research and Leadership. Fresh out graduate school, she moved to D.C. in 2004 for a public health fellowship as the local epidemic peaked. “But there are some ways that people of color, in particular, Black women have still been left behind.”

Ward also serves as the Ward 8 member of D.C.’s commission on health equity – where for the past three years she has worked to remove the social and structural barriers to residents’ well-being. Just like things like education, housing, or economic stability caused disparate COVID rates between white and Black residents, the same environmental factors drive disparities in HIV rates, according to Ward.

While Northwest D.C. is served by George Washington University Hospital, Sibley Memorial Hospital, Medstar Washington Hospital Center and Georgetown Hospital, only one hospital – United Medical Center – exists to serve wards 7 and 8. Southeast also lacks a maternal health ward, after UMC lost its obstetrics unit in 2017. Residents in wards 7 and 8 have to rely on clinics or emergency departments, or travel across the city to access care. (A long-awaited second hospital is coming to the St. Elizabeth’s campus in Ward 8, but that isn’t slated to open until 2024.) A lack of access, combined with medical racism that erodes trust between patients and providers, is one large underlying factor in HIV disparities and health equity at-large, she said.

“When health professionals don’t believe Black women, it’s incredibly invalidating. It’s dehumanizing. It makes you not want to talk openly with your medical team, if you suspect that they’re going to dismiss you,” she said. “We know patients don’t have candid conversations with their medical team, and if that’s the case, they’re gonna miss out on preventative screenings and lab testing that could really benefit them.”

Beyond access (or lack thereof) to competent care, there is also the epigenetic impact of racism that impacts one’s health; Ward cites studies of Black women from Botswana, London, and Haiti who have healthier outcomes giving birth in the U.S. compared to Black women who have lived in the U.S. for the majority of their lives. In addition to transportation, food access, and other factors influencing health, the stress and wear on the body of racism in the United States alters one’s health, or makes someone more vulnerable to worse outcomes.

“The reason Black pregnant women have a greater chance of dying than any other pregnant woman is the same reason that Black women actually have the highest rates of new [HIV] infections among all other women,” Ward said. “That’s racism.”

As a part of her equity research, Ward is studying the routinization of HIV screening in primary care offices. She started a training series that hosts monthly webinars for anybody offering primary care – be it a doctor, a physician’s assistant, a nurse practitioner – about how to integrate HIV prevention into their clinical practice. This training, coupled with regular access to a primary care physician, is one way she says the city can try to narrow the gap, and create trusting relationships between patients and providers.

Through a federal initiative, the Ryan White Program, low-income residents in D.C. can access HIV/AIDS care for free, but visits through this program decreased in 2021. While 2020 saw more than 4,000 clients who had one or more medical visits through the program, in 2021, that number dropped to around 3,000. The percentage of patients prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART) also dropped from 95% to 93%, and the percentage of clients who retained care fell from 85% to 81%.

“We need a PCP of our own who knows us, who we have established rapport with, so that we have continuity of care,” she said. “One of the things patients tell us [in our research] is an ongoing barrier to their care is seeing a different doctor every single time they go in.”

It’s also crucial that the city brings Black women into panel discussions and advisory groups, and that academics rely on Black women in surveys about HIV/AIDS, she said.

“If we, as a Black woman tell the city through needs assessments and panels, ‘you know what, it’s really hard for me to negotiate a condom because I’m also experiencing intimate partner violence,’ or ‘I don’t really feel comfortable talking to a doctor because I feel like they’re profiling me as an angry black woman when I’m advocating for my rights,’ then we’re going to be targeted with interventions that we come up with, and policy changes that will address the specific factors that reflect the reality Black women face,” she said. “That way, we can restore trust in a system that has really exploited us, mistreated us and harmed us.”

Other solutions, according to Batters-Thompson, are more frequent and accurate data measurements. The report released Tuesday is only studying data from 2021, a lag of more than a year. While it may not be possible or necessary to replicate something like a daily COVID case dashboard, she says the pandemic showed us how it was possible to produce an online, public dashboard quickly, and how beneficial that information can be to responding to spikes quickly.

“For us to respond rapidly and better evaluate programs to end HIV, we need similarly up-to-date data,” Batters-Thompson says. “A 13 to 25 month delay on getting accurate, complete data for the city is a pretty significant barrier to evaluating citywide efforts.”

D.C. is not unique in seeing pandemic-induced setbacks to HIV prevention and diagnosis. A report released last December from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nationally, HIV testing fell by about 32% in the first and second quarters of 2020, and prescriptions of PrEP fell by about 6%. Despite its progress in recent years, D.C. is still identified as one of the CDC’s prioritized jurisdictions, along with Montgomery County and Prince George’s County in Maryland. The program funnels additional resources and funding into communities with high concentrations of HIV, based on 2017 data.

This article is part of Health Hub, DCist/WAMU’s weekly segment on health in the D.C. region. Tune in to WAMU 88.5 every Tuesday or on the NPR One app for a conversation with reporters and newsmakers about local health news.

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick