Officials in the D.C. area are on the alert for possibly worsening drought conditions, after months of unusually dry weather. If the lack of rain persists, and the flow of the Potomac River continues to drop, residents could be asked to conserve water, and officials may need to release water from backup reservoirs. Most of the region relies on the Potomac River for water supply (after it’s treated).

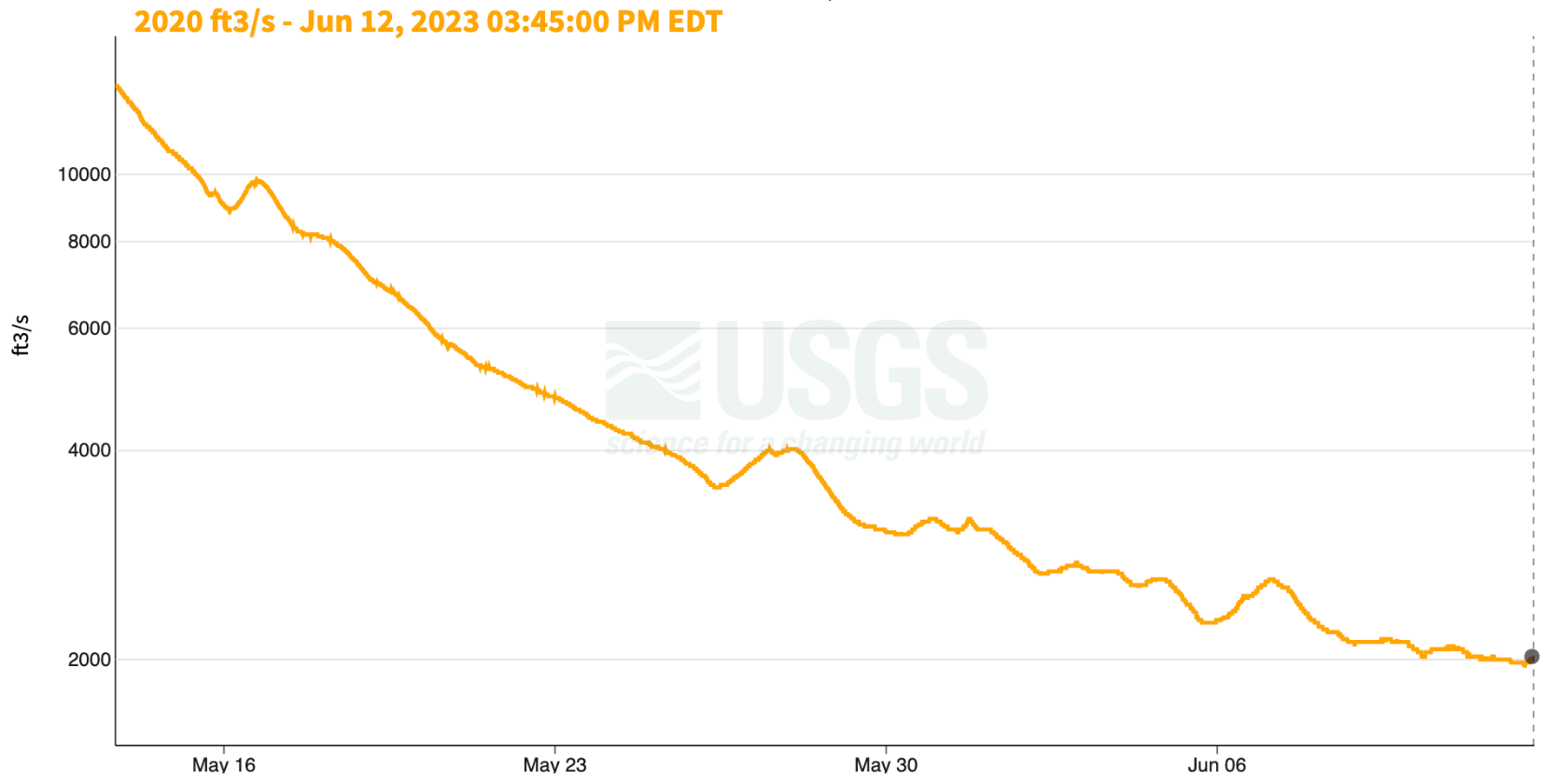

As of Monday, the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin is conducting daily drought monitoring. This is the first step officials take when a drought could cause water shortages, and it’s triggered when the Potomac River flow dips below 2,000 cubic feet per second at Point of Rocks, Md.

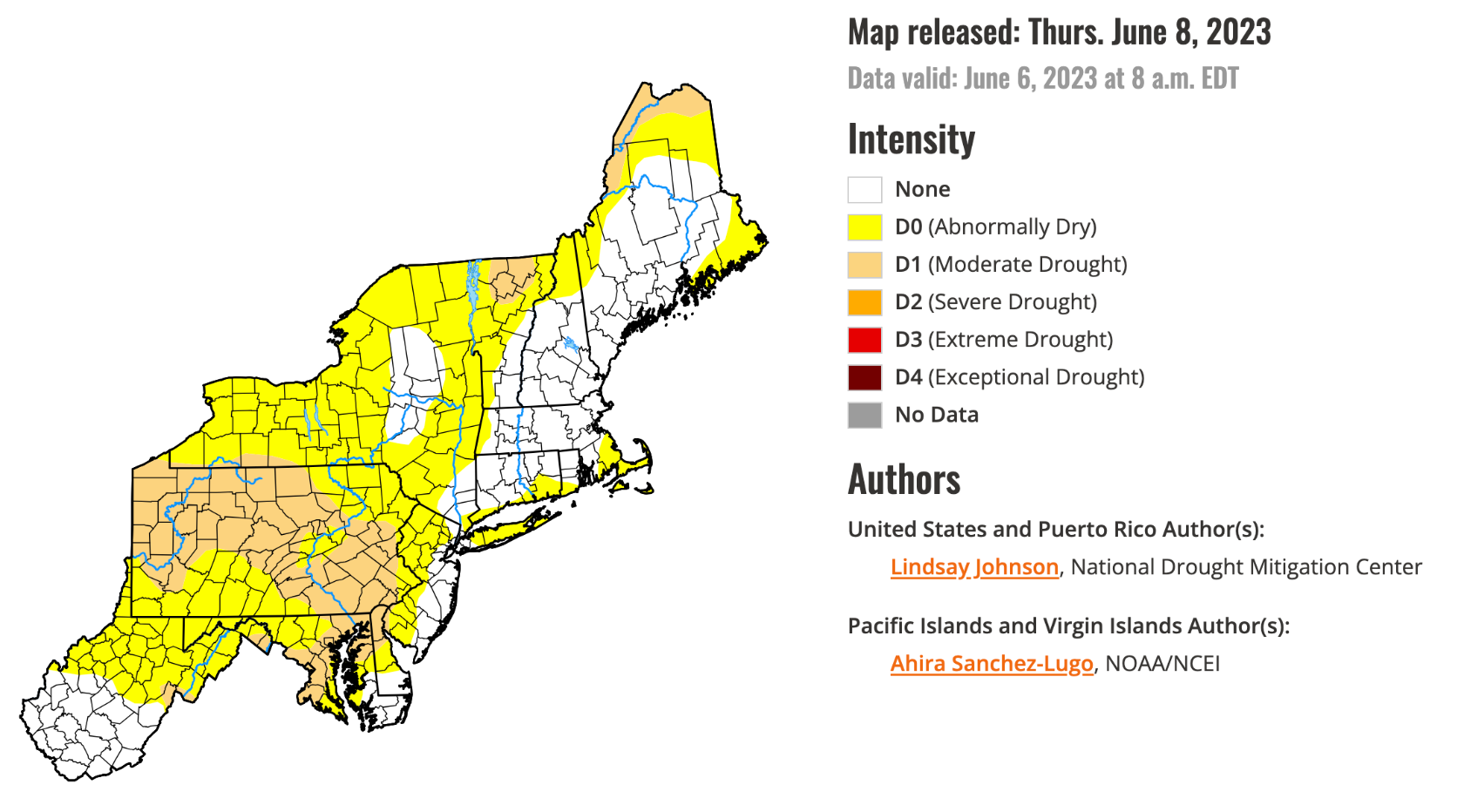

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the D.C. region is currently in a moderate drought — the least severe of four drought levels. May 2023 was the driest May on record in D.C. since 1999, with 2.4 inches less rain than in an average year. Cumulatively, over the past six months, there’s been less 6.5 inches less rain than normal in the Potomac River basin.

Mike Nardolilli, executive director of the ICPR, says daily drought monitoring involves comparing the river flow with the amount being withdrawn to supply the region with drinking water.

“We become much more cognizant of how much water is being taken out of the river,” Narolilli explains.

The first daily drought monitoring report, published Monday, shows that the region’s water suppliers withdrew 427 million gallons from the Potomac on Sunday (roughly the equivalent of 650 olympic-size swimming pools). Monday’s flow at Point of Rocks, upstream of the drinking water intakes, totaled an estimated 1.3 billion gallons (roughly 1,950 olympic-size pools).

These numbers show there is still plenty of water in the river to meet demand. Drinking water demand ranges from 400 to 700 million gallons a day during the summer, according to ICPR, and the minimum amount of water that should be left flowing in the river is 300 million gallons a day.

“If the conditions continue to worsen, then we will go from daily drought monitoring into more intensive discussions among all the water suppliers and then the states and the localities,” Nardolilli says. “Then the question is, is it necessary to trigger voluntary conservation measures?”

The next step, if dry conditions continue, would be a drought warning, which would trigger voluntary conservation measures — such as asking people to limit watering their lawns and washing their cars. Mandatory measures could be put in place if conditions worsen into drought emergency status.

While the Mid-Atlantic is not known for severe droughts, they have happened in the past, and may become more common in the future due to climate change. There were major droughts in the D.C. region in the 1930s, 1960s, and between 1999 and 2002. D.C. entered a moderate drought earlier this spring, for the first time since 2019.

Climate change is generally bringing more rain to the area, but it can also exacerbate droughts here (and wildfires).

“The basin in general is going to get wetter and hotter over time, according to our models, but variability will increase and the wetter years will be wetter, but the drier years are going to be drier,” Nardolilli says. “That’s really what we’re worried about.”

If the Potomac continues to dry up, officials could tap into several backup reservoirs. There are two upstream that feed directly into the Potomac River that can supply water to the entire region, plus two reservoirs that can supply water to Fairfax County and Montgomery County, respectively.

The Potomac is the sole source of drinking water for residents in the District and Arlington. In recent years, the ICPR and others have been urging Congress to establish a second source — perhaps by converting an old quarry into a reservoir. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.) recently won approval of legislation to study the the idea, though the study has not yet been funded.

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston