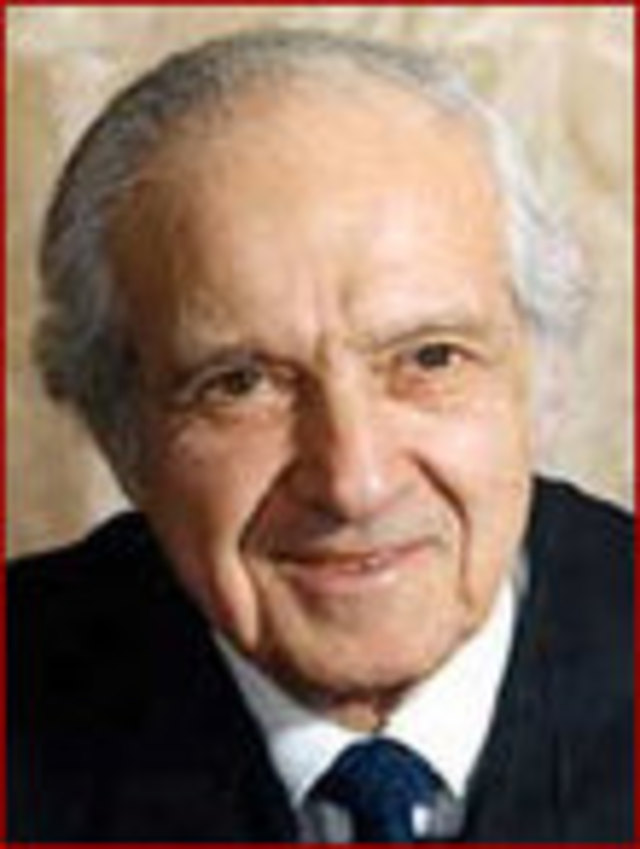

Tom Cruise may think psychiatry is bunk, but luckily for today’s mentally ill defendants, one D.C. court is responsible for reminding us of its place in the law. Judge David Bazelon (at right), one of the greats of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, single-handedly reshaped the insanity defense. The old rule, a British import, simply did not fit with the state of medicine in 1954. Though Bazelon’s new rule placed great faith in science, history has shown that Americans today are still not quite comfortable accepting it.

Tom Cruise may think psychiatry is bunk, but luckily for today’s mentally ill defendants, one D.C. court is responsible for reminding us of its place in the law. Judge David Bazelon (at right), one of the greats of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, single-handedly reshaped the insanity defense. The old rule, a British import, simply did not fit with the state of medicine in 1954. Though Bazelon’s new rule placed great faith in science, history has shown that Americans today are still not quite comfortable accepting it.

Monte W. Durham was charged with breaking into a D.C. house in 1951. Durham had been arrested on other charges before but had been committed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, where he was diagnosed as psychotic. Though eventually discharged from the hospital as mentally sound, Durham claimed he still suffered hallucinations and tested again as psychotic after he was indicted. He was nevertheless judged competent to stand trial and was convicted.

The trial court, sitting without a jury, applied what had been the standard insanity test since 1843. The M’Naughten rule, as it was called, was a product of Victorian morality and psychological theories. It held that the accused could only claim insanity as a defense if, at the time of the crime, he didn’t know the difference between right and wrong. As psychiatry became a more developed field, the M’Naughten rule became increasingly difficult to apply. Expert witnesses, with better information on mental diseases, spoke only in terms of shades of gray. The expert in Durham’s trial could not conclusively answer whether Durham knew right from wrong at the time. The prosecution’s burden of proof had been met.

The appeal featured two of America’s great legal practitioners in their prime. Durham was represented by Abe Fortas, who would later sit on the Supreme Court, and Judge David Bazelon, a great innovator in the field of defendant’s rights, delivered the opinion reversing the conviction.