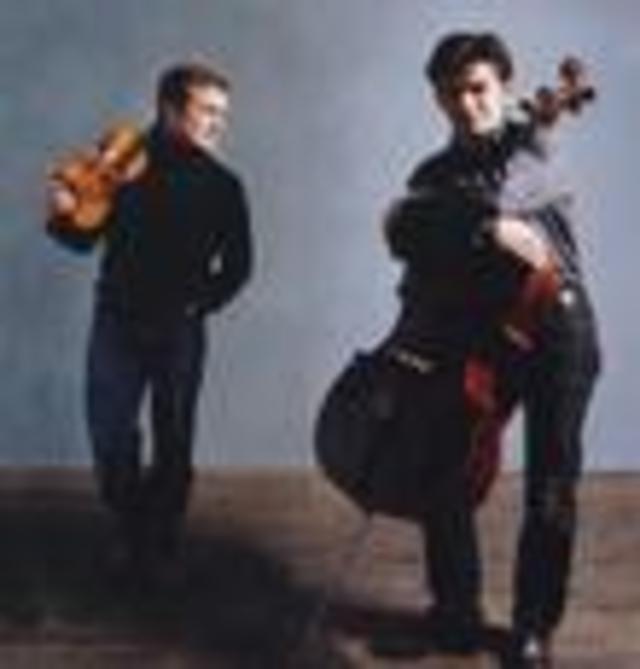

Hopefully, it was the continuing cold weather that kept people away from last week’s concerts by the National Symphony Orchestra, rather than the pathetic provincialism of Washington audiences, wary of too much modern music. If the latter is true, the names of violinist Renaud Capuçon and cellist Gautier Capuçon should have been enough to get listeners through the doors. At the Friday night concert, they played the Brahms violin and cello concerto (A minor, op. 102) with bravura, passion, and a spirit of cooperation that was inspirationally fraternal. This is appropriate enough given that the Capuçons are brothers, born in Chambéry, France, in 1976 and 1981. Although they both have independent solo careers, their performances together, as last year in recital at Shriver Hall, add up to more than the sum of their two excellent parts.

Hopefully, it was the continuing cold weather that kept people away from last week’s concerts by the National Symphony Orchestra, rather than the pathetic provincialism of Washington audiences, wary of too much modern music. If the latter is true, the names of violinist Renaud Capuçon and cellist Gautier Capuçon should have been enough to get listeners through the doors. At the Friday night concert, they played the Brahms violin and cello concerto (A minor, op. 102) with bravura, passion, and a spirit of cooperation that was inspirationally fraternal. This is appropriate enough given that the Capuçons are brothers, born in Chambéry, France, in 1976 and 1981. Although they both have independent solo careers, their performances together, as last year in recital at Shriver Hall, add up to more than the sum of their two excellent parts.

Johannes Brahms, a somber composer who often preferred lower registers to higher ones, put the cello in the lead in this late double concerto, a role that younger brother Gautier took to heart. Indeed, with the Capuçons playing, it seemed like the violin part served as an extension of its lower brother, onto higher strings, a duality encapsulated in the solo cadenzas that open the first movement, first cello, then violin, and finally the two together. These introspective moments led to an orchestral outburst of sound, which swept the movement towards an exciting finish, certainly meriting the spontaneous applause that broke out in the hall. The few notes that were sometimes dropped in this moving performance were hardly noticed because of the fiery, even edgy approach in the fast outer movements, as well as the murky, wooden sounds of the lovely slow movement. After listening to one another’s solo contributions with such intent, the first thing that the Capuçon brothers did after this fine performance was to embrace one another in sincere mutual congratulation.

Conductor Leonard Slatkin gave the second half of this program over to one of the large orchestral works of John Adams, who celebrated his 60th birthday last week. Harmonielehre, from 1984-85, takes its name from a didactic book by twelve-tone composer Arnold Schoenberg, and it was the final commission that Adams completed as composer-in-residence for the San Francisco Symphony. As Slatkin explained, microphone in hand, in a humorous and largely helpful introduction to the piece, Harmonielehre appears to be in the process of entering the general symphonic repertory, as most major symphony orchestras have played it. Some, he stated hopefully, have played the work more than once, but it is hard to think of Harmonielehre as a staple when its last and, until now, only performance by the NSO was almost 20 years ago.