Folk art is a debatable curiosity. In terms of painting, on the one side huddles a mass that does not understand why so much fuss is made over artists that cannot “paint well.” On the other side is an audience that clamors at how well these artists cannot paint. Spurious claims about the reinvention of painting are casually tossed about. What should never be in question about folk art is its quality: it is neither academic in nature nor is it avant-garde. It never intends to be either. Because of this, it is very easy to become immediately dismissive or immediately seduced.

Folk art is a debatable curiosity. In terms of painting, on the one side huddles a mass that does not understand why so much fuss is made over artists that cannot “paint well.” On the other side is an audience that clamors at how well these artists cannot paint. Spurious claims about the reinvention of painting are casually tossed about. What should never be in question about folk art is its quality: it is neither academic in nature nor is it avant-garde. It never intends to be either. Because of this, it is very easy to become immediately dismissive or immediately seduced.

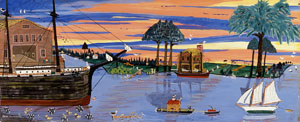

By the time Earl Cunningham took his life in late December of 1977, at the age of 84, he had seduced many with the nearly 450 paintings he produced. 50 of these works will be on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum beginning today. His life is as interesting as the content of his many paintings. Born in Maine in 1893, he left home at the age of 13 to work odd jobs fixing things. Before the first World War, he had earned licenses as an auto mechanic and a river pilot. He traveled the Eastern coastline, collecting odd trinkets and curiosities with his wife. During the Second World War he raised and sold 9000 chickens to the U.S. Army.