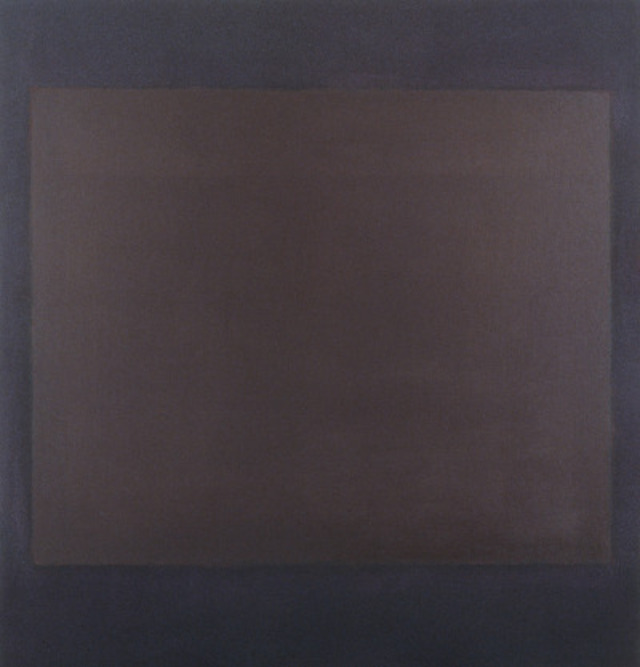

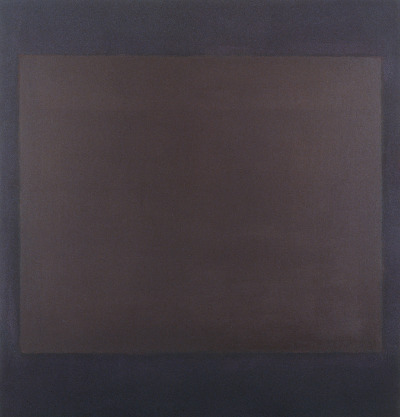

Mark Rothko’s “Untitled, 1964”, Copyright © 1997 Christopher Rothko and Kate Rothko Prizel, courtesy the National Gallery of Art

Mark Rothko’s “Untitled, 1964”, Copyright © 1997 Christopher Rothko and Kate Rothko Prizel, courtesy the National Gallery of ArtWritten by DCist contributor Danielle O’Steen

The National Gallery of Art’s Tower on the fourth floor — arguably the museum’s most hallowed space — recently welcomed a new tenant: Mark Rothko. Long the (beloved) residence of the museum’s collection of Matisse cutouts, the bird’s nest gallery now houses a rare display of Rothko’s black paintings.

As the title of the series reveals, the works are, in fact, large canvases — or monolithic forms — saturated with layers of dark paint. Absent from this installation are the colorful abstractions most associated with Rothko. (The closest visitors will get to satisfying that urge for color is a 1953 untitled fuchsia, black and orange work on the Concourse level, in the company of Clyfford Stills, Jackson Pollocks and Franz Klines.) While that is the work that has long garnered Rothko fame and popularity (and, now, a regular spot in poster shops), the black paintings offer a bit more of a challenge, which should not be missed, or quickly passed over.

Rothko began the series in 1964, near the end of his career; the artist committed suicide six years later. The artist’s turn to the black paintings has often been linked to his depression, as if they represent direct, and tragic, personal expressions. But Rothko was interested in more than his own state of mind. As was true in his brightly colors works, he was connecting modernism and abstraction to larger, overarching questions of existence, the eternal and the sublime. The black paintings, along with his colorful abstractions, are an exercise in meditating on the human condition.