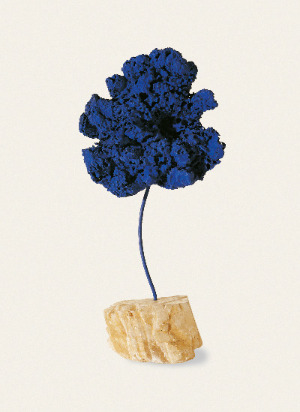

Yves Klein, “Untitled Blue Sponge Sculpture (SE 89),” c. 1960. Private Collection. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Image courtesy Yves Klein Archives and the Hirshhorn Museum.

Yves Klein, “Untitled Blue Sponge Sculpture (SE 89),” c. 1960. Private Collection. © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Image courtesy Yves Klein Archives and the Hirshhorn Museum.Written by DCist contributor Danielle O’Steen

It’s hard not to be a little obsessed with Yves Klein, especially after walking through the retrospective of his work at the Hirshhorn Museum. He was, after all, a charismatic French artist who revolutionized the traditions of art making and died young — in 1962 at age 34, after but a seven-year career — before he could falter, decay or become obsolete. Klein’s career was the stuff of legends, filled with gold, fire, naked women and a vibrant blue color made with raw pigment patented as “International Klein Blue” (IKB). To top it off, Klein held a black belt in Judo, which he earned in Japan in the early 1950s. If Klein were a movie character, he’d be James Bond in a bright blue suit.

Seriously, though, Klein continually appeals to generation after generation because of the boundaries he broke through. He redefined how an artist’s own body relates to his practice, paving the way for performance art. He determined that an idea (as well as an empty space) is worth just as must as a physical work of art, anticipating conceptual and minimalist art. He helped built the art movements that dominated the 1960s, and developed a utopian vision beholden to his own post-WWII era.

Klein emerged in Paris in 1955 at a time when artists in Europe were still reeling from the aftermath of the war. In response to the new atomic age, where, wrote Klein, “all physical matter can vanish from one day to the next,” he envisioned a release from the art object. So Klein turned to IKB, seeing the future in pure color that was free from the restrictions of art history’s line, shape, and form. He used the blue pigment, which was held together with resin, to cover the surfaces of his most signature monochrome works. Hanging in the Hirshhorn galleries, the blue canvases still emit vibrations. Klein believed they could spark an alchemical reaction, where IKB’s matter could transmit a cosmic energy derived directly from the sea, the sky, and nature herself. Klein spoke of “impregnation” instead of painting, where applying IKB to a canvas actually gave shape to a greater force.