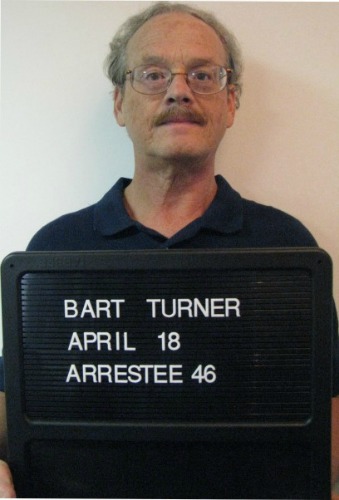

As quietly as Bart Turner was arrested, his case was dismissed.

As quietly as Bart Turner was arrested, his case was dismissed.

Today in D.C. Superior Court, a single charge of “Unlawful Entry” against Turner — a Ward 2 resident and former D.C. public school teacher who was arrested on April 18 during a one-man D.C. voting rights demonstration on the steps of the U.S. Capitol — was dismissed by prosecutors.

Despite being one of 72 people arrested during protests that spanned the spring and summer months, Turner’s case was different than that of his peers. Not only did his solo arrest attract virtually no attention — he was arrested hours before a group of ANC commissioners took to the street near the U.S. Senate in a well-publicized action; one was arrested — but he faced a more serious charge than the others. It was ultimately that charge, and a creative defense, that seemed to convince prosecutors that the case wasn’t worth pursuing.

Turner’s public defender, Stephen Jackson, opted to request a jury trial, a right afforded to those accused of “Unlawful Entry” but not those facing other minor misdemeanors. (Nine D.C. voting rights protesters have opted to go to trial, but they face charges of “Failure to Obey a Lawful Order,” which can only be heard by a judge.) Before today’s hearing, Jackson explained that a jury made of Turner’s peers — all D.C. residents — would likely be sympathetic to his plight.

Jackson also sought to pursue a two-pronged defense. First, he claimed that since Turner had told U.S. Capitol Police of his plans and asked how he could best lodge his protest without causing significant disturbance, he couldn’t be well accused of “unlawful” entry. Second, he argued that Turner had acted out of “necessity.” Citing a case involving medical marijuana activist Robert Randall, Jackson posited that since Turner was denied his basic rights, protesting was the only means he had available to be heard.

“In the face of the denial of the fundamental right to vote the only alternative that he would have to challenge the law was through the exercise of his First Amendment rights. To protest the unconstitutional denial is less serious than the denial by the government of its citizens’ right to vote,” Jackson wrote in a brief.

After the dismissal, Turner emerged from the courtroom, fully relieved that he wouldn’t have to face trial but still impassioned about the District’s lack of voting rights. Speaking in a Southern drawl that harkened back to his days growing up in Mississippi and Louisiana, Turner explained that he had been visiting the White House and U.S. Capitol for a month before he was arrested, talking to anyone who would listen about what he called a “democracy vacuum” in the District. Inspired by the 41 people that were arrested on Capitol Hill on April 11, he decided to take action — but, citing his own social anxieties, to do so alone.

“I’m hopefully going to be part of the movement to build a critical mass to get that attention of Congress. They’re not going to be moved until we start moving, and they go out to the steps of the Capitol and they look out and see throngs of people with signs,” Turner said. “I don’t intend to stop. I’m going to continue to speak out.”

Had he been convicted, Turner had planned on reading a statement to the judge explaining his actions. It’s below. The other nine voting rights protesters will likely go on trial in November.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle