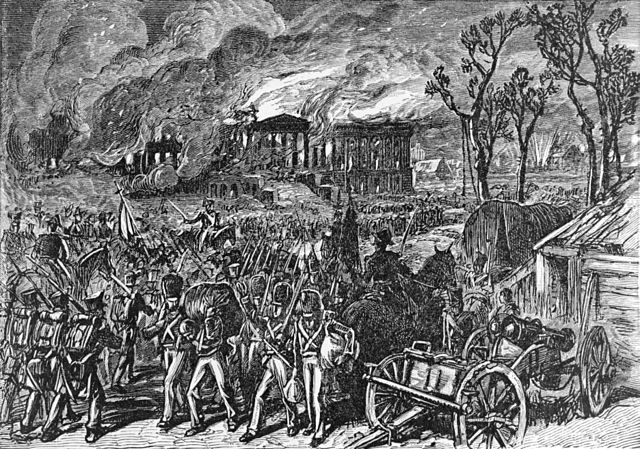

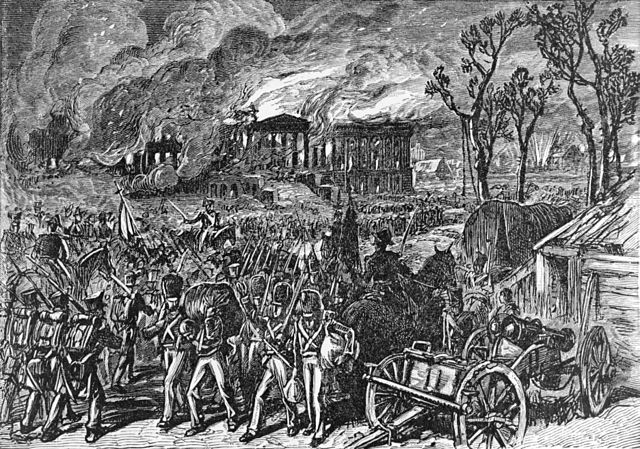

Wood engraving of the capture and burning of Washington. (Via Library of Congress)

Wood engraving of the capture and burning of Washington. (Via Library of Congress)

As a piece of architecture, the White House looks pretty good these days, driveway construction projects aside. Then again, it’s been 198 years since an invading British army torched the place.

On this day in 1814, in the throes of the War of 1812, Washington came into the clutches of the dastardly Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, commander of British troops along the East Coast of the United States, and his naval adviser, Rear Adm. George Cockburn. August 1814 was a desperate time for the still-young United States, but Britain was living large, having just dispatched Napoleon Bonaparte, freeing up numerous military assets to better prosecute the war in North America.

But the sacking of Washington wasn’t entirely unprovoked. During earlier phases of the war, American troops repeatedly attacked and set ablaze Canadian outposts—including private property—along the coast of Lake Erie. The royal forces wanted to get some satisfaction, and it was Cockburn who settled on the nascent democracy’s capital. Having sailed around the Chesapeake Bay for much of the previous year, Cockburn was familiar with the region. He was also a real bastard who recognized the political message sent by razing a national capital.

Let’s face it, we got our asses kicked on this one.

With about 4,200 soldiers and marines, Ross and Cockburn landed at Benedict, Md., after first overwhelming a meager U.S. flotilla. After that little skirmish, the British forces marched on Bladensburg, where they met U.S. soldiers in what the historian Daniel Walker Howe called “the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms.” The battle commenced at noon on August 24, within a few short hours, the Americans were retreating toward the Capitol, with the British in hot pursuit.

When Ross’ and Cockburn’s forces reached Washington, though, they won even more easily. The only resistance came from one household on Capitol Hill, which was promptly burned to the ground. From there, it was on to the White House.

Government officials fled, Dolley Madison secured a few precious valuables, but there was no stopping Cockburn. He was set on burning that sucker. The White House went up in flames, so did the Treasury Department. Cockburn even wanted to torch the offices of the National Intelligencer, a newspaper of that era, but he was persuaded to do otherwise by women living near the paper’s building who feared their homes would catch on fire, too. So instead, according to a 2001 history by John C. Fredricksen, Cockburn had the newspaper’s office torn down manually. Jerk.

Meanwhile, a separate rout was occurring across the Potomac in Alexandria. But there was no fire there. The Virginians surrendered almost immediately.

Still, why the fiery destruction of our young nation’s capital? The major battles of the War of 1812 took place along the St. Lawrence and Mississippi rivers. Washington was of little strategic or tactical importance, the historian Anthony S. Pitch argued in a 1998 edition of the journal of the White House Historical Association:

The American capital was nothing more than a gawky embryo of the city it aspired to be. Only fourteen years had passed since the capital had moved from Philadelphia, and the population had grown to little more than 8,000, one-sixth of whom were slaves. The clammy expanses of the Potomac were still almost barren and certainly bleak. The Attorney General Richard Rush described Washington as “a meagre village with a few bad houses and extensive swamps.” Augustus John Foster, who would be promoted from junior diplomat to the last British minister to the United States before the two countries went to war, lamented his posting to “an absolute sepulchre, this hole.” It was so coarse, woebegone, and lacking in refinement that in another letter home Foster wailed, “luckily for me I have been in Turkey, and am quite at home in this primeval simplicity of manners.”

Then why bother with the capital sacking? Well, it’s fun to humiliate one’s opponents. As dismal a prize as Washington presented, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, the commander of British forces in North America, wanted to give us a “drubbing.”

Cockburn’s portrait depicts the admiral standing proudly in front of Washington set ablaze, with the tip of his rapier prodding some ashen rubble. It hangs in Britain’s National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. So, congratulations admiral, your country lost the war a few months after you torched our burgeoning city, but hey, at least you got a nice souvenir.