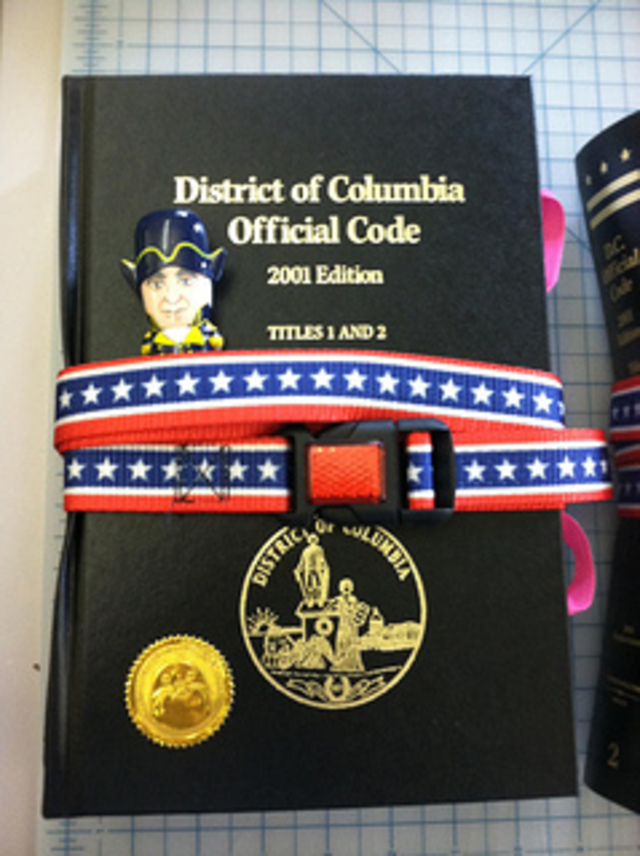

Photo by publicresource.org

Photo by publicresource.orgSitting in front of me is a copy of one volume of the D.C. Code, the compendium of laws that govern everything from criminal acts to when and how you can rent your home to a stranger. This particularly volume, which covers Titles 43-46, has seen better days: the elegantly bound book has had its pages torn from its binding, as if someone was purposely trying to take the book apart.

That’s actually exactly what happened. The man responsible for the book’s vandalism was Carl Malamud, a California-based author, activist and leader of PublicResource.org, an organization that fights to put public documents in the public domain. So why tear this particular volume of the D.C. Code apart?

Because he wanted to make a point. The D.C. Code may contain laws that affect our daily lives, but the laws themselves aren’t really ours. D.C. is one of at least 30 states that not only places a copyright upon the actual published copy of the laws, but also outsources the code’s upkeep to a private company—until late last year, it was the West Group. In D.C.’s case, the West Group doesn’t own the actual copyright of the laws, but rather how they are formatted in online and printed versions.

As a consequence, if you want a copy of the entire code for yourself, you’ve got to pay them $803.00. (You can peruse a copy at the Wilson Building or a D.C. library for free.) If you want an online version, it’s freely available—but that content is copyrighted, and links to any portion of the law expire after only five minutes. (Tom MacWright, a local computer programmer, explained why this is a problem last week in a post at Greater Greater Washington.) The copy of D.C. Council bills and the Municipal Regulations, though, are free and published by the city itself.

D.C. officials will say that outsourcing the publication of the code makes sense—not only can the West Group (or Lexis Nexis) keep up with the ever-changing provisions of the law, but they can do so more cost-effectively than the city could. But for Malamud and many open government advocates, this is a problematic arrangement.

“The principle that nobody owns the law is one that meshes deeply with the fundamental principles of the Constitution,” Malamud writes in Three Revolutions in American Law. “How can we say we are a nation of laws, not a nation of men, if we hide the law? How can there be equal protection under the law if the law becomes private property? How can there be due process if ignorance of the law is built into how it is distributed? How can there be free speech if we cannot speak to the law?”

Before turning his attention to local laws and regulations, Malamud worked with activist Aaron Swartz on a download of millions of federal court documents usually only available through a paid service known as PACER. The move caught the FBI’s attention, though no charges were filed. Swartz later downloaded academic journal article from JSTOR, a paid academic database, for which he was arrested and charged with a number of felonies. Earlier this year, Swartz was found dead in his New York apartment; friends and family blamed the government’s prosecution of him.

Many open government advocates fear the same prosecution could befall them if they cross the company that publishes D.C.’s laws; hackers have been fearful of trying to download the entirety of the code from the Westlaw page because of the potential of being found and sued. In Oregon, Malamud was threatened with legal action when he published the state’s code.

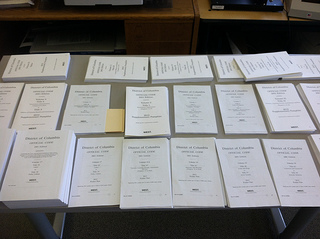

Pages of the D.C. Code torn from their bindings and ready to be fed into a scanner. Photo by publicresource.org

Pages of the D.C. Code torn from their bindings and ready to be fed into a scanner. Photo by publicresource.orgThis brings us back to the mangled volume of the D.C. Code sitting in front of me. As Malamud has done in California and Oregon, he ordered a physical copy of the code and proceeded to tear the pages from their binding. Once that was done, he fed the entire thing—hundreds of pages worth of laws—into a scanner. He then uploaded the entire thing on the Internet for anyone to peruse. For good measure, he sent me a USB drive—in the shape of George Washington, no less—with a copy for me to keep.

Accompanying the mangled volume and USB drive was a “Proclamation of Digitization,” where Malamud wrote: “It is hereby proclaimed by this notice that any assertion of copyright by the District of Columbia or other parties on the District of Columbia Code is declared to be NULL AND VOID as a matter of law and public policy as it is the right of every person to read, know, and speak the laws that bind them.”

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle