Cardozo High School in NW D.C. Photo by Ronnie R.

Cardozo High School in NW D.C. Photo by Ronnie R.

As parents and students in the District begin a new school year, the safety of children during school hours is a growing concern. How can it not be? With tragedies like the one in Newtown, Conn.— when a 20-year-old man shot and killed 20 children and six staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School—and other school shootings, it’s easy for parents to feel that school isn’t the safest place for their children anymore.

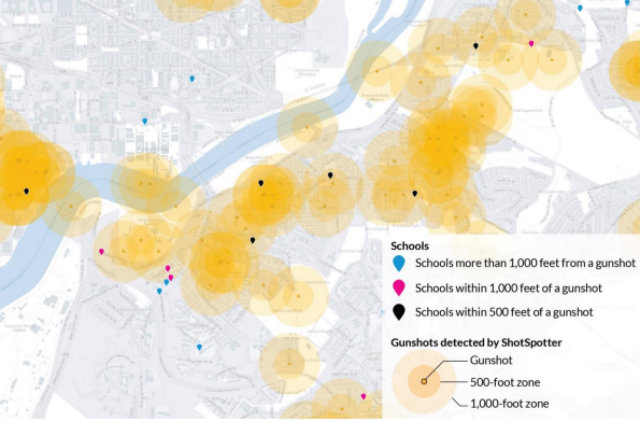

But while schools across the country have beefed up security measures to try to prevent such tragedies from happening, a new report from the Urban Institute highlights a different problem D.C. students face: the psychological effects of close-range gunfire near schools. According to the think tank’s analysis, there were 336 incidents of gunfire detected by ShotSpotter—technology that pinpoints the location of shots fired—during the 2011-2012 school year during hours when students are present. More than half of those instances occurred within 1,000 feet of a D.C. public or charter school.

The data collected and analyzed by the Urban Institute’s Sam Bieler and Nancy La Vigne also shows that, while 54 percent of D.C. schools were exposed to at least one burst of gunfire within 1,000 feet of school premises, a large number of these incidents disproportionately affected a small amount of schools. Fourty-eight percent of these close-to-school bursts of gunfire occurred near just nine percent of D.C. schools. Further analysis shows that gunfire that occurred within 500 feet of a school also happened near a disproportionately small number of D.C. schools. “Within 500 feet of 30 percent of schools there was at least one gunshot, and within the same distance of 11 percent of schools there were two or more gunshots,” the report states.

“This is clearly something that disproportionately affects a small number of schools,” Bieler tells DCist. “And I think that the next step is to figure out what the impact is on the kids specifically.” Although direct research hasn’t been conducted to see how the specific incidents that occurred near D.C. schools—like the shooting ofthree people near Ballou High School in Southeast in May—have affected D.C. students, broader research cited in Bieler’s and La Vigne’s report has shown that youth exposure to gun violence can cause “psychological challenges” like depression, anxiety, anger and other emotional stresses that can cause academic challenges to children in the classroom.

Although the analysis shows that exposure to close-range gunfire disproportionately affects a small number of schools, Bieler says that this isn’t a geographic trend in which certain schools are most affected. With the small percentage of schools that bore the bulk of gunfire incidents during the 2011-2012 school year located in all four quadrants of the city, Bieler says that it’s a problem without an easy fix. “There is a neighborhood element to this, where there’s some neighborhoods that have more gunfire than others,” he says. “But there is a spread of schools this is happening at. It’s not something you can neatly tie down and say, ‘This is an X neighborhood problem.'”

Via The Urban Institute.

Via The Urban Institute.

Bieler and La Vigne collected the data for their report using ShotSpotter—a tool used by the Metropolitan Police Department that “uses a network of acoustic sensors to pinpoint the location and time of gunfire, as well as whether one of multiple shots are fired.” MPD first started using ShotSpotter in 2006 in certain high crime areas of the city. Use of the ShotSpotter technology has since spread to cover 17 square miles of D.C. and, although that may seem like a small coverage area given the city’s 61.4 square miles, data shows that it captures and records more than 80 percent of all outdoor gunfire in the city.

“D.C. has certainly made huge strides in public safety,” Bieler says, “but I think the big question now is, ‘Can we use this new data to help kids who are exposed to gun violence to still engaged academically, still be interested in employment achievement?'”

Though SharpSpotter has helped MPD greatly in identifying the location of many gunfire incidences in the city, Bieler thinks that, given the new data he and La Vigne collected, it can be used better as a tool for community engagement near D.C. schools. “I think that is the next big step: figuring out what each of our little data kick-marks actually means for administrators and what they mean for kids,” he says. “[ShotSpotter] is a really great tool for community engagement; to help parents understand where there’s gunfire; how the community can be an active partner. Police departments and cities who are using this technology at the cutting edge, they’re making the community active partners in prevention, letting them know about what their strategies are and why they’re in areas.”

Bieler’s and La Vigne’s new report is the first of its kind. There hasn’t been any previous data about the frequency and trends of gunfire that occurs near D.C. public and charter schools mostly because “the technology just wasn’t there,” according to Bieler. Now with hard data showing just how often D.C. students are exposed to gunfire, Bieler says the next step is to focus on how that affects students and what can be done to help reduce the numbers.

“We certainly hope this is only the first step in understanding, ‘What does it mean if a kid encounters or hears gunfire on the way to school? How does that affect how he perceives his life chances?'” Bieler says. “We want to understand that. And this is really just the first step in building that out and giving communities, police, and schools the tools they need to help kids be successful academically and counteract exposure to violence.”

You can read the full report below: