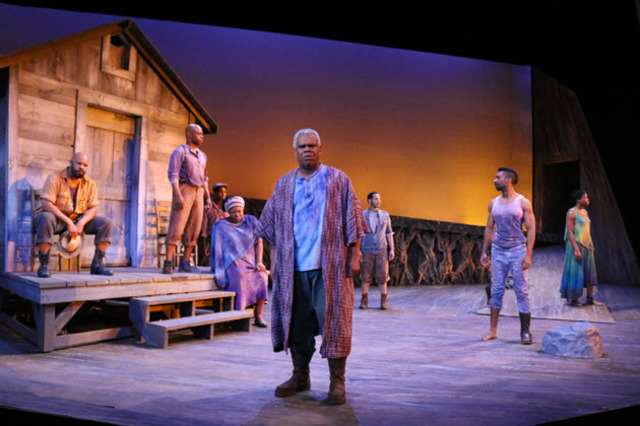

The ensemble of Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts I, II, and III) at Round House Theatre. Photo: Cheyenne Michaels

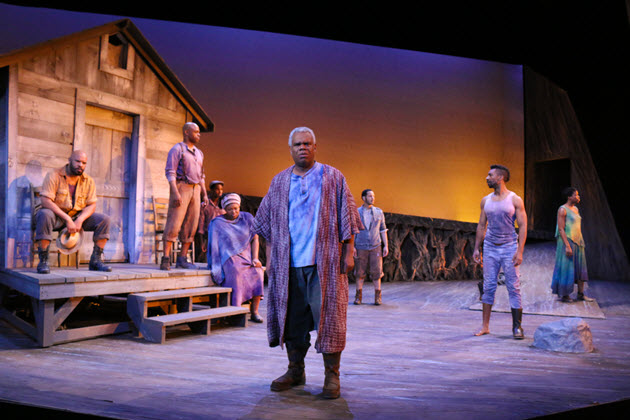

The ensemble of Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts I, II, and III) at Round House Theatre. Photo: Cheyenne Michaels

If audible hums of recognitionfrom the audience—“mhmm” and “uh-huh”—are any indication, Roundhouse Theatre’s production of Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2, and 3) could not be timelier. When an actor raises his hands above his head towards the production’s middle, in clear reference to the protest chant “Hands up, don’t shoot,” one can almost feel the chills running through the theater. The first three installments of this projected nine-part series are so relevant, in fact, that you should not wait for the remaining entries. Run to Bethesda, if you must, to experience this soon-to-be classic, interpreted with masterful sensitivity by director Timothy Douglas.

A loose adaptation of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, Father Comes Home follows the journey of the aptly-named Hero (Jaben Early), a slave in West Texas whose master, a colonel, has offered freedom in exchange for service during the Civil War. Hero is surrounded by an acquired family, comprised of the Oldest Old Man, whom Hero calls father; Penny, Hero’s “best gal;” Homer, his old friend; and a chorus of “Less Than Desirable Slaves” who contemplate the possibility of Hero’s fate. Parks crafts a surprising journey through each of the three parts, which easily and successfully occupy the production’s three hour runtime through moving twists and turns.

While Father Comes Home is arguably Hero’s story, the beating heart of this play lies within the powerful ensemble. The chorus of slaves, played by Jefferson A. Russell, Jon Hudson Odom, Stori Ayers, and Ian Anthony Coleman, often move and speak as one unit, but each actor manages a clear individual identity. In the opening moments of the play Russell and Odom are the first to meet the audience and do well setting the tone of the play’s heightened style and effortless humor. Craig Wallace, playing both the Oldest Old Man and Hero’s dog “Odyssey,” brings youthful abandon and whip smart comedic timing to his work as the dog while showing measured strength and depth in his human role. Kenyatta Rogers as Homer similarly fills the house with his tight-lipped pain, ultimately winning the audience’s favor with his vulnerable sincerity.

In the play’s second part, an isolated scene in the wilderness during the war, Tim Getman gets unsettlingly close to sympathetic as the confederate Colonel and his captive Union soldier, played by Michael Kevin Darnall, plays Parks’ psychological chess match with cool realism.

While sometimes a bit stiff in delivering Parks’ challenging verse dialogue, Early as Hero and Valeka J. Holt as Penny work beautifully together and do equally well in their scenes apart. Early, a Washington native, has a strong presence and draws the audience to Hero, despite being difficult to understand at times. Holt is so emotionally invested in her character that by play’s end you feel that you might be watching a very real moment of personal unraveling. A dead ringer for Orange is the New Black’s Uzo Aduba both in looks and artistic skill, Holt is a pleasure to watch.

Not to be outdone by the acting ensemble, Father Comes Home also boasts an appropriately interesting and successful production design. Tony Cisek’s set design and Helen Huang’s costume designs are independently brilliant, and both contribute to Douglas’ coherent and rich vision of Parks’ mythical south. Cisek’s upstage ramp appears at first to be supported by corn stalks or trees, but it quickly becomes obvious that those twisted reeds are the silhouettes of people carrying the ramp on their backs. Huang cleverly navigates the three historical periods at play in Parks’ work—the ancient Greece of the Odyssey, the Civil War South, and the present day—and the designs feel at home in the specific world of this play. Huang and Cisek also owe thanks to lighting designer Andrew R. Cissna, as he lights their work with gorgeous simplicity and seamlessly creates a believable progression of sunrise and sunset.

Director Timothy Douglas’ strong artistic vision is apparent in his strong work with the ensemble. Douglas’ stage pictures, in particular, are striking and, with Cissna’s lighting design, could make for gorgeous still photographs at any moment. Certainly, Douglas could have let the play breathe more, leaning into the silences that Parks often writes into her scripts, but one can imagine that it’s hard to resist a rapid pace with Parks’ passionate dialogue and the looming threat of a three-hour-plus runtime.

The true star of this production, however, is Parks’ script. Roundhouse Producing Artistic Director Ryan Rilette was smart to select this for the season after Father Comes Home premiered at the Public in New York last year. While Parks writes about the Civil War and the struggles of slavery, she uses that period to interrogate the value of freedom in a contemporary America where black people are routinely killed without consequence. Unlike any other Civil War narrative you are likely to encounter, Parks takes the exclamation point from behind the word “freedom” and replaces it with a question mark. This play is challenging, beautiful, and, most of all, important.

Roundhouse’s production of Father Comes Home from the Wars will demand your attention and you will be glad that it has.