Courtesy of Lindsay Grace.

Courtesy of Lindsay Grace.

Computer animated faces in film may have seemed alien to us at first, but now we’ve come to expect the new virtual reality on our screens. The Hirshhorn’s summer film series Bodies Without Organs looks at the evolution of CGI in feature films.

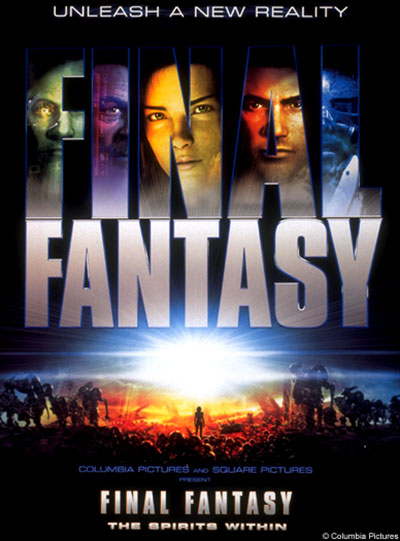

The series continues tonight with a screening of the 2001 film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, which broke new ground as the first photorealistic computer animated feature, but fell into obscurity as a massive box office bomb. Lindsay Grace, the founding director of American University’s Game Lab and a successful game designer in his own right, will introduce Monday’s screening. We spoke with Grace about the film’s legacy, the future of video games, and virtual reality.

DCist: Can you give us a little background on your work in non-gamer terms?

Lindsay Grace: I’ve been teaching game design for about 12 years. I’ve designed and implemented and released scores of games. Primarily what we call casual games in the mobile space. But I also do gaming in the art space. I’m an MFA and we do something we like to call “critical gameplay.” It’s a bunch of games designed to critique the way we play video games to remind people of the assumptions we make in the way we actually interact with video games. The instinct that you handle all of your conflicts by destroying your enemy is just one way of framing play, but it’s not the only way. We remind people of the other approaches that are available.

Courtesy of Lindsay Grace

Courtesy of Lindsay GraceOne of my games that’s gotten a lot of press is Big Huggin’ which is a little like Super Mario Bros, where this little bear runs into obstacles, but instead of destroying the obstacles, the controller is a tiny teddy bear, and you hug the bear to move forward in the game.

DCist: So, a lot of the work you do is designed to challenge the modern gaming ideal where you just explode things and shoot people in the face, then?

Grace: Exactly. I also direct American University’s game program. We run a traditional graduate program, but we also run a studio whose main focus is applying games to non-game context, particularly for social impact. One thing we’re doing right now is implementing a treatment for anxiety where we take the power and engagement of video games and apply them to spaces where they improve people’s lives. We also have games around improving consumption and production of news, to try to help the ailing news industry through understanding the principles of game design and how the game industry has succeeded through all its change.

DCist: The film series tracks the history of CGI, transforming film from celluloid and human skin to digital recreations of reality. When Final Fantasy came out, it was this huge deal, technologically. It’s technically a video game movie but has very little to do with the game series. What are your thoughts on the film as an extension of that mythology?

Grace: If you look at the context the film was made in, well, let’s be honest, mistakes occurred. They wanted to piggyback off of the popularity of the game franchise, but if you look at the script for the film, the script was trying to do far more. The film is trying to integrate, not quite Shintoism, but certain Japanese cultural references to the idea of spirit and everything having a spirit, even inanimate objects that Western society might not think of as having a spirit.

That theme comes into a movie and that movie then tries on top of that to be one of the biggest technological innovations in film history, so it was an extremely expensive film that tried to do more than it could have or really should have. So, mitigating that by trying to attach itself to the Final Fantasy intellectual property wasn’t enough. I think if it had just been The Spirits Within it would have been easier and more palatable for general audiences, because they wouldn’t have had the Final Fantasy expectation. But then I don’t know if people would have even seen it.

DCist: Or if it would have been made in the first place.

Grace: Exactly. It’s basically the predecessor to something like Avatar, but that was successful because it didn’t attach itself to an existing property. It was its own thing.

Courtesy of the Hirshhorn

Courtesy of the HirshhornDCist: The movie was the first to map realistic human faces to characters being voiced by actors who look nothing like what we see on screen. It was really jarring.

Grace: It’s the uncanny valley. The challenge here is they went for photorealism. When I teach my students and we talk about design, we always talk about how it’s a good idea to get as far on the abstract side as you can, while still employing all the tricks you want for your narrative. If you watch something like one of the Madagascar films, Alec Baldwin is a lion, but you certainly didn’t say “Wow, that lion looks nothing like Alec Baldwin!”

Most animation tries to integrate elements of the voice actor into the design of the character, and with Final Fantasy they didn’t do that at all. They cast voices after designing the characters because of the investment that was already there. The plan for Square Pictures was to make the characters reusable for subsequent films, which is a common practice in video game design. You invest heavily in the first assets and you want to use it across five games because it’s very expensive to do. They planned to do the same thing with the film, so I guess that’s why the characters are so divorced from the performers.

DCist: It’s not that different from the modern Hollywood machine where you invent a cast of characters and trot them out in sequels to get more return on your investment.

Grace: But here was the first time they designed virtual actors that they hoped to reuse again and again, which is something very common in the gaming world.

DCist: Where do you see the relationships between film and video games as storytelling mediums going in the future?

Grace: I am personally not a big proponent of virtual reality, but right now, I think the confluence is actually in that space. With 360 degree cameras and people starting to produce films for virtual reality devices, there are a lot of questions that remain unanswered about how to draw someone’s attention. In traditional linear films, you have control of the camera and you move the viewer’s head, but when you start moving your own head and controlling what you want to watch, they have to employ fewer filmic approaches and more gaming approaches.

So, in a video game, you’re given free range. But in a role playing game, we might need you to go into a cave, so in order to get your attention on the cave, we might employ a couple of lures. So, besides the obvious of like, shining a light on it, we might introduce a non playable character who strongly suggests you go there. If you don’t use that, you use spatial cues, like creating a path that draws you to the cave. These are new concepts for filmmakers who are used to saying “look here, and now you look here.”

DCist: The difference between writing a novel and a choose your own adventure story.

Grace: Yes, so a lot of that is interesting, but also one of the most interesting tidbits is this idea that now a lot of nudity that is shot is 3D layered, so an actor can portray nudity, but the actual nudity is added in post.

DCist: It’s as if audiences are getting more used to those unreal elements. Most of the hangar scene in Captain America: Civil War is all digital and very few people seemed to mind, but years ago those elements would have stuck out like a sore thumb.

Grace: Yeah, for example, car racing is my hobby. In the last Fast & Furious, there’s this ridiculous car crash that is insane and impossible to do with real cars and people look at it like, “Yeah, that’s all right.” So, it’s like, if this was real, it’d be a phenomenal stunt, but people are so used to the imagery that it’s just fine.

DCist: There’s a stigma that digital manipulation is like cheating. People react more viscerally to real stunts because they can watch the making of featurette and see a stunt man almost die to get the shot and it feels more real to them even if none of it is actually real to begin with. Do you feel that there’s an imbalance between film or paint or sculpture versus digital art, because there’s this perception that if it’s done with a computer then anyone can do it?

Grace: There’s a real tension in the fine art world between the traditional mediums and digital creation that permeates at every layer. The challenge is that it’s hard for museums to show really interactive exhibitions on a technical level, so that difficulty informs the way it’s perceived, but also, there’s this question of authenticity that comes with digital media that people don’t ask of , say, a painter. With a painter, you know what they did. They put brush to canvas.

Something like The Spirits Within required a lot of resources and hundreds of computers to render it. The question becomes what did the artist do and what does the computer do? But if we take a step back, there was a time when you had to mix and make your own paint in order to paint at all. Now when we see a painting, we assume the artist bought that paint, but we know that they arranged that paint to make their art. In digital media, we may have different rendering tools, but the artist is still using those tools to produce the work. The problem is the art world hasn’t caught up to an understanding of the process and an appreciation of the process. But that is more of a Western concern than an Eastern concern.

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within screens Monday, June 20 at 7 p.m. in the Ring Auditorium. (Independence Ave SW & 7th St SW) Free