Cynthia Nixon and Tim Matheson (National Geographic Channels/ Hopper Stone, SMPSP)

Cynthia Nixon and Tim Matheson (National Geographic Channels/ Hopper Stone, SMPSP)

The made-for-TV drama Killing Reagan paints a sometimes fascinating portrait of the conservative icon—if you’re willing to rummage around for it.

Following in the footsteps of Killing Lincoln and Killing Jesus, the movie is based on a book by Bill O’Reilly (and co-writer Martin Dugard). But director Rod Lurie’s adaptation is more of a departure than the other projects in the Killing series. At the Newseum premiere last week, O’Reilly called the film being apolitical, a respite from partisan issues in this contentious climate. National Geographic CEO Courteney Monroe agreed, choosing to focus on the film’s attention to historical detail.

They’re not entirely wrong. The finished product boasts fewer factual inaccuracies than O’Reilly’s book, and the narrative is less divisive than anything you might see on the news. But it’s still something of a mess, shrinking the timeline of the book to just the six months surrounding John Hinckley‘s assassination attempt and overstuffing that space with conflicting plot strands.

The movie at first seems split between two arcs, Ronald Reagan (Tim Matheson) ascending to the presidency on a collision course with the diminishing mental capacity of his would-be assassin John Hinckley (Kyle S. More). On its face, that’s not the worst way to dramatize such a calamitous event. But as the tension mounts and we get closer to March 30, 1981, the movie splinters into a frustrating variety of other narrative concerns, each with their own distinct tone. This results in an inconsistent movie that hopscotches between comedy and tragedy with discomfiting abandon.

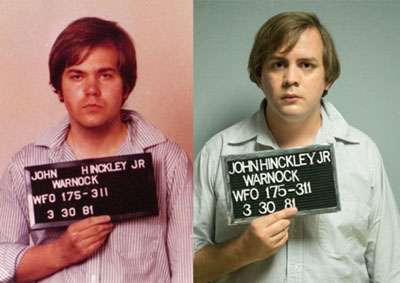

Kyle S. More (right) in a recreation of the mugshot of John Hinckley Jr. (left). (National Geographic Channels/ Hopper Stone, SMPSP

Kyle S. More (right) in a recreation of the mugshot of John Hinckley Jr. (left). (National Geographic Channels/ Hopper Stone, SMPSPThe Hinckley arc is perhaps the most frustrating. More delivers a strong performance as the gunman, but his origin story is riddled with laughable moments that undermine the threat he posed. Hinckley is presented as the ’80s equivalent of a Reddit trolling neckbeard who lashes out at his own impotence. That isn’t a bad reading, but it’s executed so indelicately as to border on parody. It does, however, contrast smartly with the romance between Reagan and his wife Nancy (Cynthia Nixon).

If the film is proudest of anything, it is in the depiction of Ronald and Nancy’s singular love. Matheson’s Reagan is a workmanlike performance, teetering ever so mildly into caricature, but grounded in a relatable sincerity. Nixon and Matheson have a palpable chemistry, and its clear their closeness is meant to anchor the rest of the movie. But there’s just something fundamentally oddball about their rapport. Painting the president as a motivated, but clueless performer desperately in need of outside direction is fascinating, but the Pollyanna tenor of his marital interactions winds up more grating than inspirational.

Killing Reagan‘s best scenes are its least necessary. Detailing Alexander Haig’s passive-aggressive coup attempt adds nothing to the proceedings, but Patrick St. Esprit is such a thrilling, unintentionally hilarious screen presence. The Haig material was better portrayed in The Day Reagan Was Shot with Richard Dreyfuss, but here he arrives right at the point in the movie where mentally checking out seems a logical option. Esprit’s cartoonish interludes are manna from heaven before the endless final act begins.

The assassination attempt should be the climax, but Killing Reagan limps on for what feels like forever as the President recovers, grasping wildly at differing closing moments in hopes of accidentally finding a thematic bow to wrap things up with. It never quite finds that catharsis.

Killing Reagan debuts Sunday, October 16th on National Geographic at 8 p.m. EST