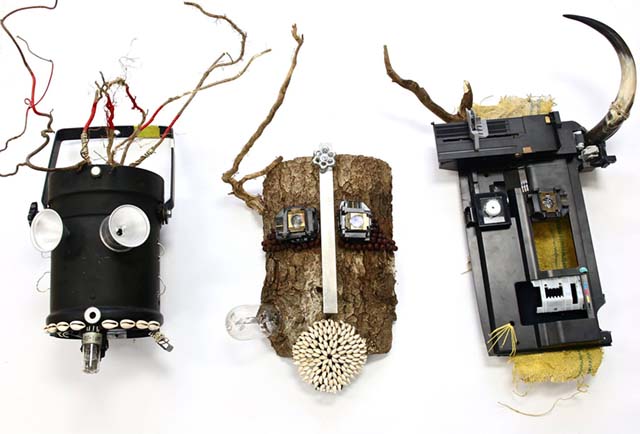

Pierre Bennu, from Future Artifacts (Honfleur)

Pierre Bennu, from Future Artifacts (Honfleur)

A similar cosmology and sense of ordering the world can be found across the African diaspora. Yet, as curator Niama Safia Sandy, a Howard alumna, explains, we still don’t think of each other as connected. “What can we do to push the needle on that?” she asks.

The group show, Black Magic: AfroPasts/AfroFutures, presents works across multiple disciplines. The artists demonstrate that the concepts of magical realism and Afrofuturism are necessary survival tactics for black and brown people.

To discuss the origins and inspirations for the exhibit with Sandy is to delve deep into the concept of black diaspora, and what unifies African descendants across varied lands and forms of artistic expression.

Sandy first explored magical realism in literature, and realized that this language of expression existed beyond the written word on a larger continuum of black expression alongside Afrofuturism. She began to see a larger truth about black art as a whole, crystallized in Paul Gilroy’s 1993 book, The Black Atlantic, in which the author, a professor of Literature at King’s College London, expounds on musical acts like Soul II Soul.

“What he says is that black music is essentially black people creating a world that’s safe for them, because nowhere else is,” Sandy recounted. “I thought, what black creative expression isn’t that way?”

The show features the work of nine artists, a third of whom are D.C. based. Each uses various media to echo the core concepts at the heart of the exhibition: that afrofuturism and magical realism are merely nodes on the spectrum of black expression, acting as creative technology for self preservation.

Afrofuturism can be seen in the mainstream as surface level chic, a style to be commodified. But Sandy’s approach proves such reduction is a disservice. “This is not merely an aesthetic,” she explains. “This is about survival.”

To understand Sandy’s assertion, one need look no further than artist Pierre Bennu’s series Future Artifacts, one of the central bodies of work featured in the exhibit. Bennu has created interpretations of ceremonial West African masks for our times, crafted from salvaged pieces of modern technology.

While these masks traditionally were created for specific rituals and spiritual needs, Bennu has conjured a fascinating mythology that theorizes a future where historians might look back at these masks to put our world in context. For example, a mask made from the discarded pieces of a stage light comes from a culture that shone a light on celebrity, but the mask itself was designed to protect one’s face from the omnipresent surveillance state.

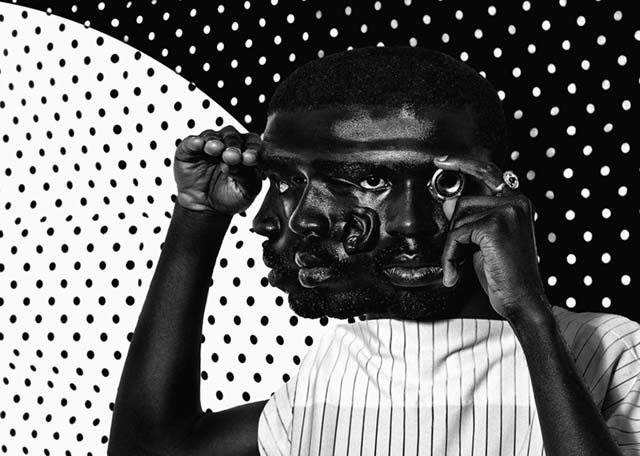

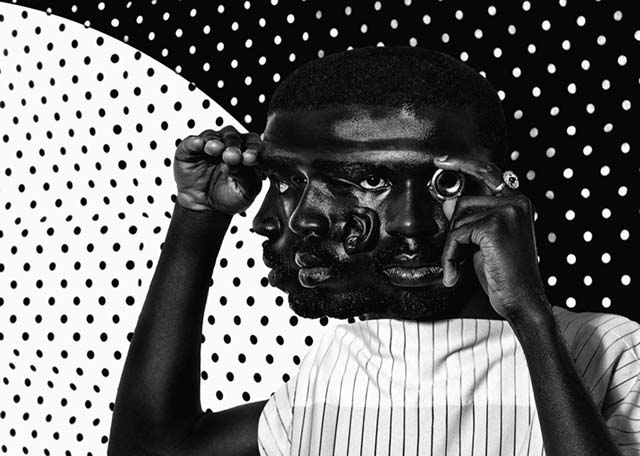

Ivan Forde, Satan On The Bare Outside Of Our World, 2012. From the Transformation series (Honfleur)

Ivan Forde, Satan On The Bare Outside Of Our World, 2012. From the Transformation series (Honfleur)

Similarly, each artist showcases their interpretations of the black experience. Visual artist Adrienne Gaither recontextualizes family portraits into the recognizable iconography of playing cards, dramatizing the concept that that your kinfolk are the hands you’re dealt with in the poker game of life. The implication is central to the ideas Sandy hopes to explore.

“Who are we?” she asks. “And how are we who we are, if not through what is left for us? What’s locked into our blood?”

While wrestling with the present and looking forward to potential futures, the exhibit also seeks to reconcile with our collective pasts. “I had the gift of being able to go to the African American History Museum the weekend that it opened,” Sandy recalled. “It just struck me how little has changed.”

Anyone watching the news this week should have little difficulty understanding where that feeling comes from, but Adama Delphine Fawundu, an artist featured in the Brooklyn iteration of the exhibit, will present a new series called In The Face of History. Fawundu made screenprints of archival documents, like headlines ripped from the antebellum South, where she’s placed herself inside each of the prints.

“What does it mean to observe history?” Sandy asks, expanding on the series. “What does it mean to be present?”

Black Magic presents an opportunity to see powerful works of black art as necessary suits of armor for surviving in a dangerous world. Yet they won’t serve merely to protect; this is art that will educate, illuminate, and inspire.

Black Magic: AfroPasts/AfroFutures runs from August 19—October 7 at Honfleur Gallery (1241 Good Hope Road SE. The opening reception is on August 19 from 5—8 p.m. The related Black Magic Short Film Festival will be held on August 20 from 3—6 p.m.. An artist talk will be held on September 16 from 5—7 p.m. Gallery hours are Wednesday—Saturday, 12—7 p.m.and by appointment.