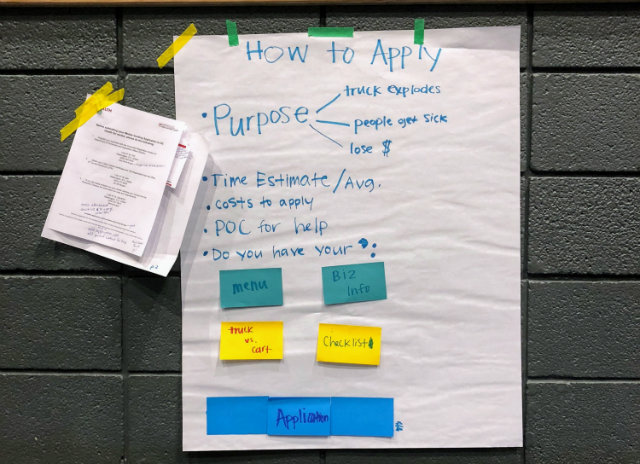

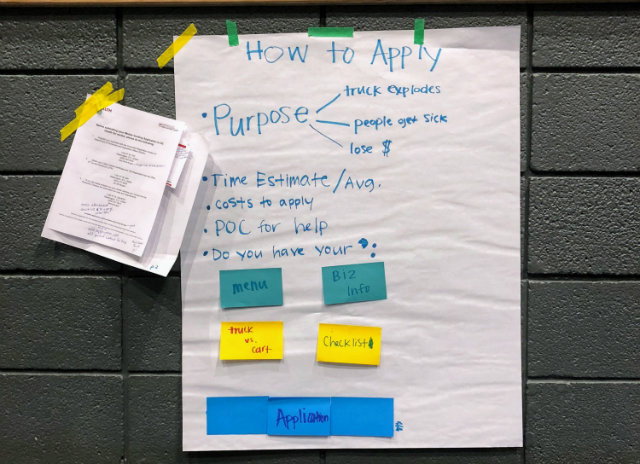

Participants at Form-a-palooza worked to redesign five D.C. government forms to be more user-friendly. (Photo by Helen Wieffering)

Participants at Form-a-palooza worked to redesign five D.C. government forms to be more user-friendly. (Photo by Helen Wieffering)

By DCist contributor Helen Wieffering

If you’ve applied for a D.C. driver’s license in 2018, chances are you did less squinting than the applicants who came before you. If you purchased a home this year, you may have actually scanned your property for peeling paint before signing the lead disclosure form. Both of these forms were recently redesigned under a District initiative to help residents better understand and access government services.

Rather than requiring details on your ‘’MEDICAL FITNESS,’’ the driver’s license application now gently prompts you to “Tell us about your medical history.” The lead disclosure form has shed its legal references to lessees, lessors and Code § 8-231.15(b), and instead guides residents in plain language toward practically assessing the risks of lead exposure at home.

This large-scale effort to ease the pain points surrounding government paperwork was kickstarted by The Lab @ DC, a diverse group of scientists and academics working within Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration to improve District policy and programs. The Lab held its first-ever Form-a-Palooza last summer, facilitating a day-long event for residents and city officials to work together to rethink some of our most commonly used forms. On Saturday, The Lab hosted Form-a-Palooza round two.

“It’s so nerdy,” remarked one volunteer as participants filed in early that Saturday morning; “it’s just so nerdy.”

The day began with a keynote speech from Crystal Hall, associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington, who emphasized the behavioral science and decision-making at play when we interact with forms. Too often, she said, policy or paperwork is designed with the assumption that we know what we want and will take logical steps to get there—we’ll read the fine print, in other words.

But “we actually are really malleable” Hall said. “We’re human, and we need a little bit of help.” When time or resources are scarce, our attention is often elsewhere, and the layout or wording of a form can have an impact on how accurately we report our information, or whether we choose to fill out the form at all.

Nominations for this year’s forms, five in total, were crowdsourced and ultimately selected to represent a diverse array of issues, ranging from disability parking spaces to food truck vending. Participants divided into classrooms at Ron Brown High School to create a prototype for a new and improved version of the form of their choice. Agency representatives floated nearby, answering questions about how each form is used.

Though self-selected, groups saw an impressive mix of backgrounds. The team charged with remaking the child care subsidy application was composed of graphic designers, educators, and homeless services case workers, as well as D.C. residents who had never seen or encountered the form at hand.

Bringing together this mix of perspectives is important, says David Yokum, director of The Lab @ DC. From psychology to user experience design, “a lot of different fields have a lot to say here. But the one key part of this approach is putting the user front and center in how you’re doing the redesign.”

Certain aspects of the forms proved easier to overhaul than others. The child care subsidy application has a complex coding system for reporting race and citizenship status that could easily be replaced with checkboxes, the classroom agreed. References to mother, father, and spouse could be changed to the simpler label of parent/guardian. But using color to highlight or delineate sections of the form was controversial, since not all child care centers have access to color printers. Every detail of the redesign should be rooted in the form’s specific context.

“Our goal is to help people,” Anthony Lyons, city manager of gainesville, Florida, noted during his presentation on citizen-centered design. “People don’t come to our office for a permit; they come to open a business.” Simple paradigm shifts like these, Lyons suggested, can help the government work better for everyone.

Of course, there are limitations to what Form-a-Palooza can accomplish in a single day. A confusing form often reflects a complicated policy, and sometimes the form is less a barrier to the government benefit than the bureaucracies that surround it, as comments from case workers made clear.

In the case of child care subsidies, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education recognizes thirteen different categories of eligibility, each with its own set of required documents that are listed online. (The ten-page checklist is buried in the uninvitingly-titled “Eligibility Determinations for Subsidized Child Care Policy Manual”). If even one of those documents is missing, applicants will need to return to the office within thirty days—a requirement that weighs heavily on needy families.

“There are more problems with policy than there are with design,” one participant offered when Yokum asked the crowd for takeaways at day’s end.

Yet even setting aside the question of design, Form-a-Palooza proved a valuable opportunity to share knowledge and foster connections among disparate offices of the District government. Agencies had the chance to hear from constituents firsthand, and residents had a direct line of communication for their questions. If nothing else, Form-a-Palooza could serve to humanize the “back-end bureaucracy” so many Washingtonians confront when they interact with the D.C. government.

Whether or not teams ended the day with a prototype that resolved every issue with their forms, Yokum was confident that the feedback and questions raised on Saturday would lead into the final redesign in the months to come.

“This is not a hypothetical exercise,” he said. In 2017, the District rolled out its redesigned forms just two months after Form-a-Palooza.

The Lab has applied many of the same concepts behind Form-a-Palooza in its efforts to increase recertification for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, a cash assistance program that requires families to annually verify their eligibility. The Lab helped redesign the program’s reminder letter using the insights of behavioral science. Ongoing A/B testing against the current version of the form will help measure the impact of redesign efforts like these.

Without a consulting firm or a design house to carry the torch of Form-a-Palooza past 3 p.m. on Saturday, each government office will be responsible for pushing the form overhaul forward using insights from the day’s events.

As Yokum says, one of the goals of Form-a-Palooza is to raise the capacity for redesign efforts to happen spontaneously and of their own accord. “Armed with a little bit of knowledge and a little bit of inspiration, you can go pretty far.”