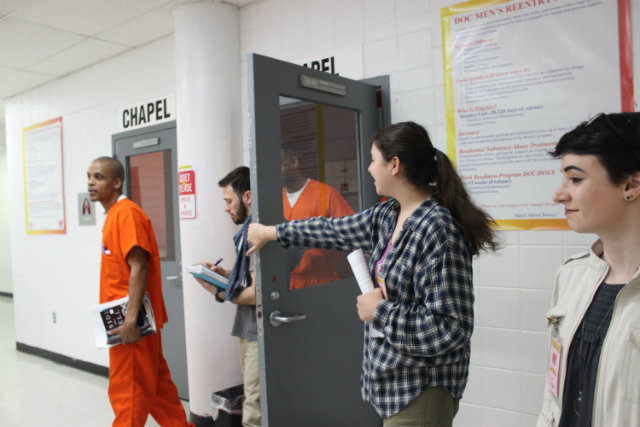

Georgetown students and D.C. Jail inmates are peers in the “Music in U.S. Prisons” course. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

Georgetown students and D.C. Jail inmates are peers in the “Music in U.S. Prisons” course. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

When half of your classmates are inmates, you go to them.

On a bright, hot Friday morning toward the end of the spring semester, about a dozen sleepy Georgetown University students loaded themselves into a white 16-passenger van for their weekly drive across town to the D.C. Jail.

The class was called “Music in U.S. Prisons,” a college-level course taught by Ben Harbert, a lanky, blue-eyed associate professor in Georgetown’s music department. Harbert put the course together for the inaugural semester of the university’s Prison Scholars Program, which offers a variety of classes to inmates in the D.C. Jail. Several of the course offerings, including Harbert’s, were “inside-out” courses made up of both inmates and Georgetown undergraduates.

Students met every week for three hours to examine how the criminal justice system, prisons and jails, and their musical traditions are connected.

On this particular Friday, Harbert led the class through a discussion about singing in solitary confinement. After he gave a brief lecture, an inmate named Jeffrey Bell raised his hand.

“I was once on lockdown, and I used music as rehabilitation,” said Bell, whose long dreadlocks were pulled back in a low ponytail. “I used to snap in my cell until my fingers split open, until I couldn’t snap no more.”

Joel Caston, Sophie Poole, and Michael Woody discuss their plan to create a music production program at the D.C. Jail. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

Joel Caston, Sophie Poole, and Michael Woody discuss their plan to create a music production program at the D.C. Jail. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

Harbert tied Bell’s story back to a text they’d read earlier in the semester. His teaching style was unapologetically academic, which particularly suited some of the inmates. Some had master’s degrees, and one had a Ph.D.

“I like the way he can go into different philosophies and theories about music – things that I have claimed to know intuitively or through experience,” said one inmate, who asked that his name not be used.

“It’s not watered down,” said Amy Lopez, a deputy director at the jail who oversees the education programs. “It’s real college-level work.”

Other students, particularly those from Georgetown, said they wished class left more time for sharing personal experiences from their different lives. Despite their shared interests in music and social justice, the divide between the two groups was always present. Most of the inmates were D.C. natives, while none of the Georgetown students were. The Georgetown students earned college credits for the course, but the inmates didn’t.

And at the end of class, the college kids had quiet dorm rooms or apartments they could use to study or make music. But in jail, there was sound everywhere.

At one point, a mundane announcement from a jail official blared over the loudspeakers, interrupting the class. The students and Harbert laugh it off, but constant noise was a real issue for inmates who wanted to make music, not just talk about it.

Bell was one of those students. Toward the end of class, he performed a song he’d written called “Oh My God.” He said it was the first time he’d ever performed for a group.

Elizabeth Gleyzer, a Georgetown sophomore, asked if he had any way of recording it. Yes, he said, but it wasn’t easy. He could use the jail’s landline to call out to his cousin, who’d record Bell’s tracks for him in a recording studio. But the call could only last 15 minutes, and the phone system would butt in with regular interruptions (“You have one minute remaining,” Bell mimicked).

Inmates were escorted to their cells after class, and Georgetown students headed back to campus. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

Inmates were escorted to their cells after class, and Georgetown students headed back to campus. (Photo by Mikaela Lefrak/WAMU)

That was part of the reason why, despite the class’ successes, it wouldn’t run again in the fall. Instead, Harbert was replacing it with a music recording program that the students had helped him create.

Inmates will have access to recording equipment and learn how to edit songs from Harbert and guest artists. There will also be a mental health element to the course: The jail’s medical director has committed her department to helping Harbert study the effects of “chaotic sound,” as he called it, on inmates.

“It would’ve been crazy if I would’ve come in, even with a Ph.D. in music, and believe I had a solution to all this,” Harbert said. Funding for the program hasn’t been fully sorted yet; as of right now, most of the work will be volunteer-based.

As the class was wrapping up, and the students were talking together in small groups, Gleyzer was messing around on an old electric piano, so Harbert suggested they sing “Amazing Grace.” Everyone knew the words, and no one seemed in a rush to leave.

Finally, it was time to go. The inmates were escorted back to their cells. The Georgetown students went back to campus, where they had exams to study for and dorm rooms to pack up. It was just days before summer break, and for them, freedom was right around the corner.

It turned out that freedom was just around the corner for Jeffrey Bell, too. He’s now out of jail, and no doubt able to write his music in a much quieter place.

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Mikaela Lefrak

Mikaela Lefrak