The walk through a wildflower-dappled meadow to Glenstone Museum’s gleaming new gallery takes seven minutes, designed so the visitor’s worldly cares fall away during the journey.

From the Arrival Hall, also newly constructed, The Pavillions appears first like a mystery in the distance. Getting closer to the 204,000-square foot building of stacked concrete blocks doesn’t exactly clarify what the expansive-looking structure is.

But one thing is immediately apparent: It’s stunning.

Glenstone is a private museum on 230 acres of land in Potomac, Md. It was opened in 2006 by Emily Wei Rales and Mitchell Rales, a duo of married “co-conspirators,” in their words, looking to meld the disciplines of landscape, architecture, and post-World War II art. According to Forbes, Mitchell is the 652nd richest billionaire in the world, worth about $3.8 billion.

This expansion, which opens to the public on October 4, represents a $200 million project that took the better part of the decade to complete. Glenstone held a media preview of its new space on Friday.

As museums like the Renwick and the Hirshhorn find success in making the visitor experience easy to capture on social media, Glenstone is taking a decidedly different tack.

“You go see the Mona Lisa with 400 of your friends,” says Thomas Phifer, the architect who designed The Pavilions. “The thing we wanted desperately to find was how to slow that experience down … It’s really hard to explain this building in photographs. This building is about experience. It has to do with how you move.”

Trying to capture the grandeur of the space with a camera feels fruitless—even a panorama frames things far too tightly. (And then attempting to post those photos online in a place with such limited service … good luck.)

The intention seems to be to create an inward reaction rather than outward replies (and likes and retweets). Phifer describes wanting visitors to feel “weak at the knees” when they see the artwork. Emily Wei Rales said she’d like to “slow the pulse” of museum-goers.

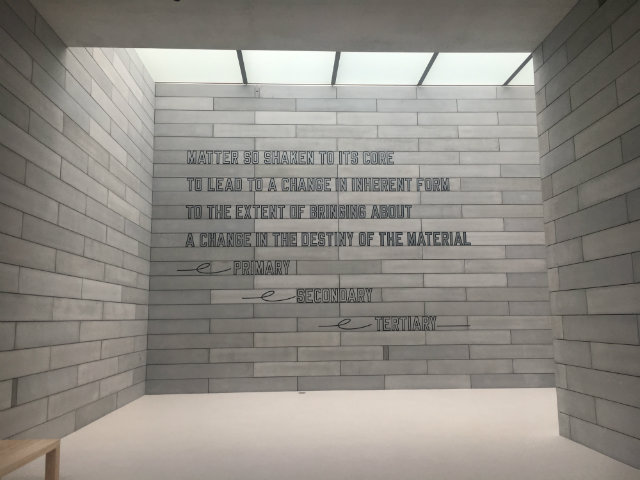

Visitors enter The Pavilions and a 2002 work by Lawrence Weiner greets them.

Lawrence Weiner’s “MATTER SO SHAKEN TO ITS CORE TO LEAD TO A CHANGE IN INHERENT FORM TO THE EXTENT OF BRINGING ABOUT A CHANGE IN THE DESTINY OF THE MATERIAL PRIMARY SECONDARY TERTIARY.” (Photo by Rachel Kurzius)

Lawrence Weiner’s “MATTER SO SHAKEN TO ITS CORE TO LEAD TO A CHANGE IN INHERENT FORM TO THE EXTENT OF BRINGING ABOUT A CHANGE IN THE DESTINY OF THE MATERIAL PRIMARY SECONDARY TERTIARY.” (Photo by Rachel Kurzius)

Should we view that as the museum’s mission statement? “You could if you want to,” says guide Chelsea Bright.

The guides, all donning comfortable-looking gray uniforms that resemble what nurses might wear in a dystopian space station novel, provide background information on all of the art (there are no wall didactics beyond the name of the artist and work), though they’re just as happy to hear your musings on its meaning.

Descending the stairs, visitors reach what’s called The Passage. Its walls are floor-to-ceiling glass and it surrounds a verdant, 18,000-square foot lily pond, deemed the “Water Court”, that boasts 10 different plant species. Off of The Passage are 11 rooms of different materials and dimensions, nine of which are dedicated to single-artist installations.

Many of the artists on display chimed in on the lighting or materials for the rooms, says Phifer. Room 4 holds Robert Gober’s Untitled installation, which has forest-themed walls, ever-running sinks, piles of newspapers, and barred windows. In Room 1, two wooden Martin Puryear sculptures, including one of a Phrygian cap, contrast with the lily pond in clear view. Room 11 has five Cy Twombly sculptures spanning four decades, chosen with the artist’s help. Room 5 has no ceiling, and guides carefully count how many people head in (out?) at a time. That’s because Michael Heizer’s Collapse is a huge 24-by-36-by-16 foot hole filled with 15 steel beams.

Room 2 is the bustling metropolis to the other rooms’ more suburban spread. Wandering through it is a bit like a crash course in modern art history. Artwork from 52 artists, like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Alexander Calder, Yayoi Kusama, to name just a few, from 1943-1989 unfold in mini-rooms in a close-to-chronological order, with an emphasis on themes like abstract expressionism, pop art, and pre-minimalism. It’s the museum’s “Greatest Hits” album, and each tune helps show the inspiration for what follows it.

Another exception is Room 7, a viewing gallery with books and an 18-foot long bench that looks out on the sloping meadow. It’s perhaps the most beautiful room of all. After about five uninterrupted minutes of sitting on that bench and looking at the landscape, says Phifer, “time drops off.”

Bright, one of the guides, says that the building’s near-total reliance on natural light means that many of the works look entirely different depending on the weather. “I can’t wait to see what it looks like when it’s snowing,” she says.

Phifer is also taken by the light, and just as much by its absence. “We need to be praising the shadows as much as the light,” he says. “You know, shadows come from the light.” He wants visitors to feel beckoned by the passage of light as they circulate The Pavilions.

Cyclic rhythms are at the heart of the The Glenstone experience—in the daily passage of the sun, the shift in seasons, and even The Pavilions’ artwork, which can be rotated (some, like that in Room 2, more easily than say, 15 steel beams in a huge hole in the ground).

Entrance to the museum is free, though it requires a timed ticket. “We will always be open for all, for free,” said Emily Rales, speaking publicly to the media in front of the water court. “We hope it will expand audiences for art.”

But there may be another motivation, too. Private art museums have often been criticized as tax-avoidance schemes, and Glenstone was one of almost a dozen museums whose tax-exempt status was investigated by the Senate Finance Committee in 2015.

The Rales family says they see it differently. “This will be our gift to the world,” Mitchell told the press. He said that he lived in a “glass house” on the property, and could see the visitors, which “enthralled” him as they visited the first outpost of the Glenstone, the gallery designed by Charles Gwathmey and the many large-scale outdoor installations from the likes of Jeff Koons, Andy Goldsworthy, and more.

This expansion isn’t the end game for the Glenstone, either. The never-mowed meadows, designed by Adam Greenspan, won’t reach their zenith for at least another five years.

And even then, when the grass grows much higher than it does now, the private museum won’t be completed. “We’re not at the end, we’re not at the beginning,” said Mitchell. “We need another 15 years to get the model right.”

Glenstone is located at 12100 Glen Road in Potomac, Md. Entrance is free but requires a timed ticket. The next batch of tickets will be available on October 1.

Rachel Kurzius

Rachel Kurzius