Studies show that minority students fare worse in D.C. than even in other parts of the region. (Photo by Tyrone Turner / WAMU)

Studies show that minority students fare worse in D.C. than even in other parts of the region. (Photo by Tyrone Turner / WAMU)

There is a pattern of racial disparity in educational opportunity, attainment and school discipline practices in the Washington region, according to 2015-16 school year data recently released by the U.S. Department of Education and consolidated by ProPublica.

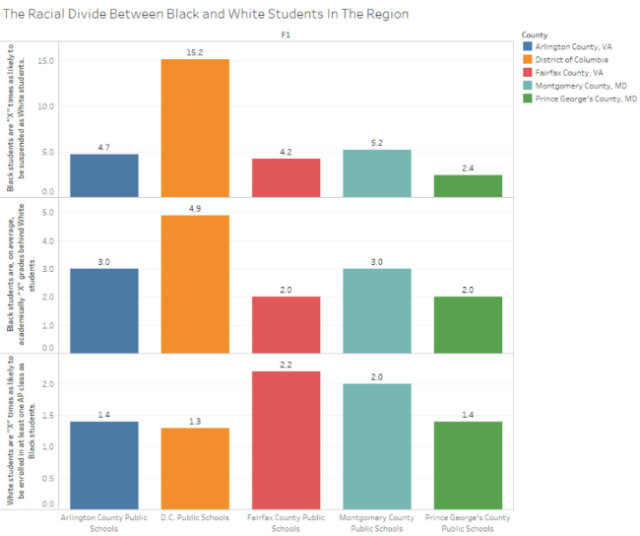

In almost every school district, black and Hispanic students are more likely to be behind grade level than white students, more likely to be disciplined and less likely to be enrolled in at least one advanced placement course.

And statistics show that minority students fare worse in D.C. than even in the surrounding areas.

Compared to other states, black students in D.C. charters and traditional public schools are 11.7 times more likely than white students to be disciplined. And in D.C. Public Schools (DCPS), black students are 15.2 times more likely to be disciplined. These rates are significantly higher than other states and neighboring school districts.

Discipline data in the District has historically been tricky to measure. Charter schools and DCPS classify discipline actions differently, making comparisons difficult. The data from the Department of Education and ProPublica takes into account in-and-out of school suspensions, expulsions, arrests, student referrals to law enforcement and transfers to alternative schools, among other indicators. For the 2018-19 school year, a new law meant to curb punitive disciplinary actions against students went into effect, and is expected to result in an overall drop in such actions.

Within the region, after D.C., Montgomery County has the second highest rate of suspensions for black students. They are 5.2 times more likely than white students to be disciplined. Prince George’s County, in contrast, has one of the lowest racial disparities gaps in the region in school discipline between black and white students.

The racial divide between black and white students in the region. (Data from ProPublica, graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

The racial divide between black and white students in the region. (Data from ProPublica, graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

A closer look at D.C. Public Schools also shows a significant achievement gap between black and white students, according to data on academic disparities from the Stanford Education Data Archive. The archive pulled test score data from the 2008-09 to 2014-15 school years, to show “the average difference in grade-level equivalence of students from different racial groups.”

The data shows that black students average 4.9 grade levels behind white students in DCPS. By comparison, New York City Schools show a 2.3 grade-level gap, Chicago Public Schools, a 3 grade level gap and L.A. Unified, a 3.1 grade-level gap.

Black students in both Arlington and Montgomery County Public Schools are, on average, 3 grade levels behind their white peers. Black students in Fairfax and Prince George’s County are only two grade levels behind their white peers.

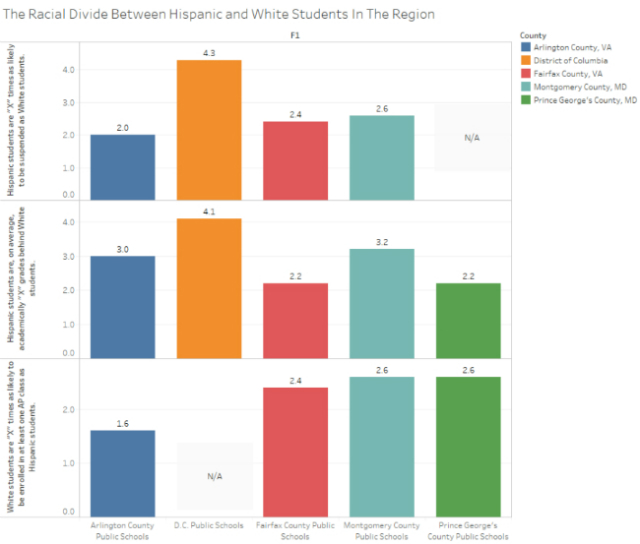

Hispanic students are also, on average, several grade levels behind their white peers.

The racial divide between Hispanic and white students in the region. (Data from ProPublica, graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

The racial divide between Hispanic and white students in the region. (Data from ProPublica, graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

Similar Populations, Big Differences

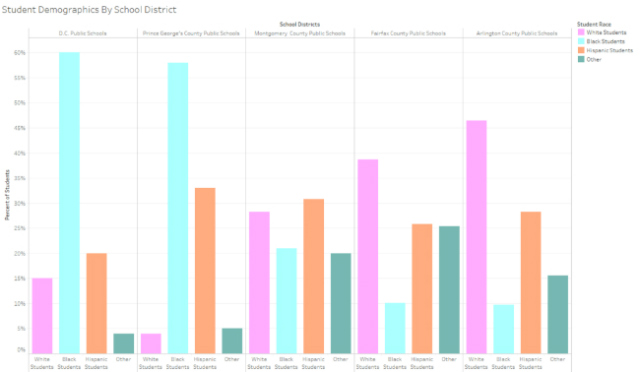

Both DCPS and Prince George’s County have a significant number of minority students. Sixty-four percent of DCPS students are black, compared to 60 percent in Prince George’s County. DCPS also has an 18 percent Hispanic student population, while Prince George’s County has 30 percent. Yet, Prince George’s County comes closest to closing racial divides in the region, while DCPS has one of the highest racial disparities.

Student demographics by school district. (Graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

Student demographics by school district. (Graphic by Jenny Abamu / WAMU)

There are many factors that can lead to racial divides, but the policies the two districts have in place related to discipline could be one reason behind the dramatic differences in outcomes.

In 2013, Prince George’s County put a three-day limit on suspensions for “soft offenses such as disrespect, insubordination and disruptions in class.” DCPS officials only recently revised its disciplinary policies, which will be rolled out over a three-year period. The revisions came after the D.C. Council passed a bill earlier this year forbidding suspensions for minor infractions such as uniform violations or disrespect. The bill asks all schools to focus on positive behavior enforcement and reserve harsher punishments like out-of-school suspensions and expulsions for “only the most serious offenses.”

Although neither policy directly addresses race, both measures were put in place after questions into racial disparities in disciplinary data.

Jacqueline Naves, the supervisor of pupil personnel services at Prince George’s County says her district’s focus on the “root causes” of behavioral issues is what has driven down the number of suspensions.

“It might be the child is misbehaving in school because of other factors that are happening to them. It could be something at home like maybe they didn’t have enough to eat,” says Naves, in which cases her department works with partners to provide students with food. They have also recently hired someone in the central office whose fulltime job is to help educators respond figure out how to respond to negative classroom behavior in positive ways.

Acting Deputy Mayor of Education, Paul Kihn, noted that though D.C. has seen a significant drop in suspensions, from 11,078 in 2013-14 to 6,695 in 2015-2016 — a 40 percent reduction, the District still had a lot of work to do.

“We are very eager to understand deeply how our African-American, Latino and White students are doing individually. And this study really reaffirms something that we feel like we already know, which is that we have really unacceptable racial and income disparities among our students in our schools,” says Kihn. “That is why the mayor and I have made closing the achievement gap, put it at the very top of our agenda. Equity is the most important thing we are working on, and I think this study reminds us why that is so.”

Kihn says he is already seeing improvements, noting that he visited a school in the district this week that had 20 to 25 suspensions by this time last year, but only has one suspension to date.

This story originally appeared on WAMU.