Organizers of an upcoming film series at the Washington National Cathedral that explores racist policing know watching two Oscar-nominated movies about the practice won’t solve the problem.

What they’re hoping is that the movies—Do the Right Thing and BlacKkKlansman—open a window into a different space, put audiences into a narrative they may never experience in real life, and raise questions about who we want to be as Americans.

“When we talk about police brutality, it’s a symptom of a wider problem and it can become an entry into a wider conversation into racial justice,” says The Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, one of the film festival’s three co-founders and the cathedral’s canon theologian. “I hope people come open to being provoked—not in a hostile kind of way—but being provoked to think.”

A Long, Long Way: Race and Film, 1989-2019 will spend Friday and Saturday screening and discussing two powerful Spike Lee films that explore the intersection of race and policing when it comes to African Americans.

Friday is reserved for Do the Right Thing, Lee’s explosive 1989 movie that takes place on the hottest day of the year in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn—well before gentrification pushed out many longtime residents and turned it into another trendy neighborhood. In the movie, tensions between black neighbors, the white owner of a local Italian pizzeria, and police boil over and end in tragedy. Do the Right Thing was nominated for two Academy Awards for best supporting actor for Danny Aiello and best original screenplay, but did not win.

The next day, the cathedral will screen BlacKkKlansman, Lee’s 2018 film set in the 1970s that tells the true story of Ron Stallworth. It dives into how he, the first black detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department, infiltrated a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan.

The movie was released on the first anniversary of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va. in which white supremacists demonstrated against removing a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee from a park. The rally turned violent as protestors clashed with counter-protestors, killing one person, injuring many others, and shocking the nation.

Lee, 61, included footage from the rally in BlacKkKlansman, and the movie is up for six Academy Awards including best picture, best supporting actor for Adam Driver, and a first-time best director nod for Lee, whose career spans four decades.

Panel discussions after both movies will be moderated by NPR newscaster Korva Coleman and include a lineup of film critics, theologians, academics, and writers.

Beyond that, a two-hour Saturday afternoon workshop on film, race, and policing will precede the BlacKkKlansman screening to examine how identity shapes the way we understand policing and film and how much progress Americans have made to end racist policing in the 30 years since “Do the Right Thing” was released.

Police brutality, harassment, and racial profiling have continued since the movie’s 1989 release and in recent years spurred the Black Lives Matter movement. The only difference between 1989 and 2019 is that technology lets people shoot cellphone videos of the discriminatory behavior and post it on social media for the world to see, Douglas says.

“A wider section of America is able to see what people of color have been navigating all of their lives,” says Douglas, also dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Seminary.

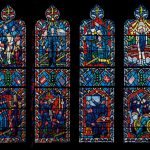

The film series is part of the cathedral’s wider commitment to racial justice and to starting conversations about race. In 2017, leaders removed two stained-glass windows portraying Confederate leaders Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Conversations surrounding that decision led to a renewal of focus on programming that tries to understand people’s experience around racial reconciliation and justice, says film festival co-founder Michelle Dibblee, the cathedral’s director of programs.

“The windows reignited the conversation about what racial justice and reconciliation look like, what old symbols of the past meant then, what they mean now, and how to respond to them,” she says.

The next year, Douglas, Dibblee, and Dr. Greg Garrett, an English professor at Baylor University in Texas and the event’s third co-founder, launched the cathedral’s festival A Long, Long Way: Race and Film, 1968-2018. That year it juxtaposed Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner with Get Out.

The festival’s name comes from a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who frequently said about racial justice, “We have come a long, long way, but we still have a long, long way to go.” The cathedral has a unique connection to the slain civil rights leader — on March 31, 1968, King delivered his final Sunday sermon from the cathedral. Four days later, he was fatally shot in Memphis.

Festival attendees should expect a provocative conversation about provocative films, and Dibblee wants people to come to the festival with open minds.

“We’re hoping for the experience of challenge and curiosity and new ideas and ways of seeing that film can help make happen for us,” Dibblee says.

A Long, Long Way runs Friday-Saturday at the National Cathedral. Tickets $15