It has long been a favorite talking point for D.C.’s elected officials: 1,000 new people moving into the city every month, making it one of the fastest-growing jurisdictions in the country.

But what was once a rapid and enviable clip of population growth in the nation’s capital has slowed somewhat in recent years, so much so that 2017 to 2018 represented the slowest year of growth in a decade.

That’s according to a December analysis of new Census numbers by the D.C. Chief Financial Officer. According to those numbers, D.C.’s population in July 2018 was 702,455, an increase of 6,764 people over the year prior. That represents the 13th straight year of population growth; since 2005, the city’s population has jumped by 135,319 people.

While overall growth numbers still provide enough to boast about—the last time D.C. had more than 700,000 residents was in 1975—the growth from 2017 to 2018 was roughly half of the average from 2008 to 2018, when a few more than 12,000 people were added to the city’s rolls annually.

Breaking it down further, the CFO’s analysis found that while that 10-year period saw an average of 3,581 people added annually to the city’s population from other parts of the U.S., from 2017 to 2018 close to 1,000 people actually left the city for other parts of the country. (The other elements of population change—natural increases, or births minus deaths, and international migration have stayed somewhat steady over the years.)

So what gives? Are D.C.’s high housing costs dissuading people from moving to the city or the region? Is it crime, or schools? Is it something less tangible, like people staying away from the nation’s capital because of the state of the country’s politics?

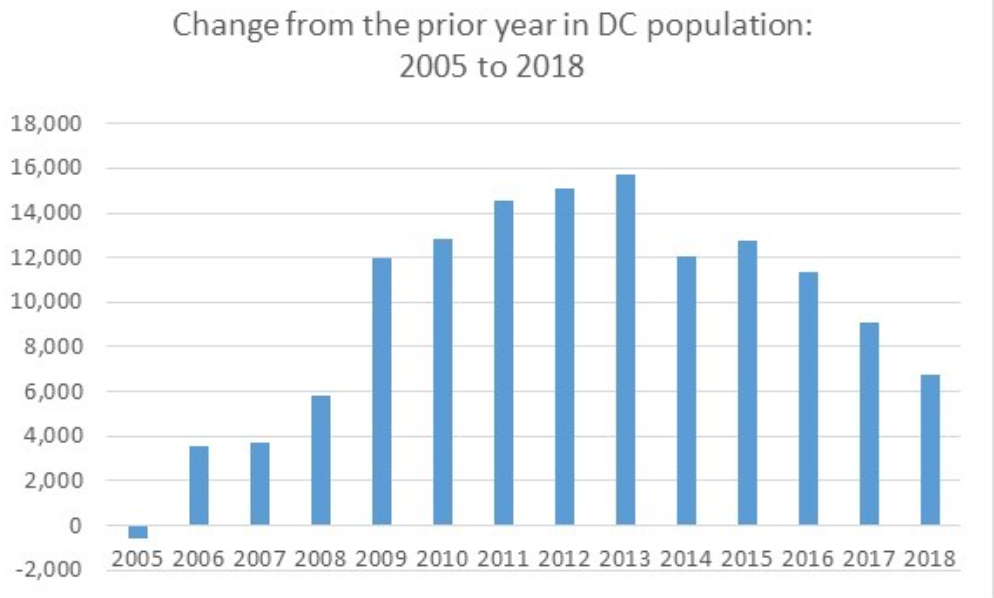

This graph shows the year-to-year change in D.C.’s population growth. People steadily moved into the city from 2006 to 2013, but since then the number of people coming in has declined from the year before it, save 2014 to 2015.Office of the D.C. Chief Financial Officer

“We were growing at a very fast clip, and we all expected some leveling of that growth,” said Mayor Muriel Bowser when asked about the slowing growth this week.

Demographers and population experts say she is somewhat right: That the city’s population growth has slowed is to be expected, especially since the overall national economy has been humming along recently.

“When the national economy is doing well, we typically have a larger outflow of residents. If there are more opportunities for you with a lower cost of living, more people are more likely to take that up. People tend to retire at greater rates during good economic times as well, and they often leave the Washington region because it’s a high-cost area,” said Jeanette Chapman, deputy director at The Stephen S. Fuller Institute at George Mason University.

Chapman says that the Washington region is “a little countercyclical.” That means when recessions hit, more people are attracted to D.C. and the surrounding jurisdictions because of the steadier offerings of jobs. But when the national economy picks up, the opposite happens: People leave.

The Census data crunched by the CFO shows as much. D.C.’s population started ticking up in 2007, and jumped somewhat dramatically from 2008 to 2009 — the height of the Great Recession — growing steadily through until 2013. After that, the population growth has continued, but each year being a little slower than the one before it, save 2014 to 2015.

Chapman says that D.C.’s slowing growth is part of a regional trend — but that the city is losing people a little more slowly than the region as a whole.

“The return to cities and the amenity-based improvements, the schools’ improvements, the crime improvement, all of those have factored into a little bit more growth potential for the District proper, which we’ve seen, so that growth lasted longer in the District compared to the rest of the region,” she said.

While the state of the national economy has an important role to play in the pace that the Washington region’s population grows, the cost of living in and around D.C. is also an important factor.

“I think housing costs, and the increasing housing cost particularly in very desirable neighborhoods and certain communities, clearly is a challenge for those jurisdictions and for our region. People do have to make that decision, that tradeoff,” said Paul DesJardin, the director of Community Planning Services at the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments.

“You hear anecdotes all the time of people making the tradeoff: ‘I’m well-educated, but this is just going to be too expensive, too hard of a place to try to make it,’” he said.

That’s ultimately what drove the decision for Nick Darby, a 24-year-old statistician who was offered two comparable jobs right out of grad school in two very different places.

“My options were go to D.C. or go to Columbus, [Ohio]. The money was about the same, and I didn’t want to be living in D.C. trying to pay D.C. housing prices,” he said. “Housing near everything in D.C. is crazy. But I’ve got a two-bedroom apartment that I’m renting for myself [in Columbus] for $1,000, and that’s pretty great.”

In 2015, an analysis by D.C.’s CFO found that while people who moved to the city during the 2000-2014 timeframe most often cited jobs as they reason, the ones who left during that same period said housing and housing costs were the reason why.

Chapman says that while the Washington region has consistently attracted young residents and then lost some of them as they started families, things like the region’s increasing cost of living has prompted some changes in those patterns.

“There are some warning signs with our millennial cohort. We’re not retaining them to the same degree at a regional level that we used to,” she said.

DesJardin says that the increasing cost of housing—and the lag in building enough to keep pace with expected job growth in the region — is an issue that local jurisdictions are now taking up. A COG analysis last September said the region would have to build 100,000 more housing units than currently planned by 2045 to keep up with the jobs expected to come.

All told, says Chapman, while population growth has slowed regionally in recent years, it’s not a doom-and-gloom scenario. It’s just part of a cycle.

“Forecasts are very often presented as a straight line, because we don’t want to create more angst about forecasts than is necessary. In reality, things do not move in a straight line. There are cycles to these patterns, and there will continue to be cycles to these patterns,” she said.

“The long-term growth trajectory of the District’s population is still positive. There may be ebbs and flows to the degree to which it’s growing, that’s natural, but in the long term it’s still growing,” she added.

The era of the 1,000-new-residents-a-month may be over, but D.C. is expected to keep adding people for the foreseeable future. And the one thing that is likely to ensure that is international migration, which includes both non-citizens coming from other countries and U.S. citizens repatriating after a stint abroad.

“The international immigration, both in the District and the region, even in the face of high housing costs, continues fairly strong. And as a percentage it’s actually been very steady,” said DesJardin. “Were it not for the international immigration, we actually would have had jurisdictions that would have experienced population loss.”

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle