Many waterways in the D.C. area are polluted with plastic. But it’s not just bottles and cups and bags: the rivers and creeks also are filled with pieces of plastic so tiny they are barely visible. The Anacostia River, in particular, has a plastic pollution problem — in fact it’s one of the only rivers in the U.S. officially designated by the EPA as impaired by trash. The nonprofit Anacostia Riverkeeper recently tested the water in four locations, looking for microplastics, which have been a growing source of concern among scientists and environmentalists in recent years.

“We found basically microplastics in every single sample we collected,” says Robbie O’Donnell, a project coordinator with Anacostia Riverkeeper. “You can see a bottle of water, you can see a plastic bag, you can see a tire,” says O’Donnell. You can remove those large pieces of plastic from the water or shoreline with relative ease, using trash traps, skimmer boats or volunteers. Microplastics — which can be as small as a hair follicle — are impossible to remove on a large scale.

One study released this month concluded modern Americans ingest and inhale between 74,000 and 121,000 microplastic particles each year — even more if they drink bottled water instead of tap water.

Microplastics have become ubiquitous in the environment, and in aquatic life — scientists in Belgium found microplastics in commercially cultured oysters — 50 particles of microplastics per serving.

Closer to home, researchers tested four Chesapeake tributaries for microplastics. They took 60 water samples in four rivers — the Patapsco, Magothy, Rhode and Corsica — and found microplastics in all but one sample. They also found “statistically significant positive correlations with population density” — in other words, the more people near the waterway, the more microplastics.

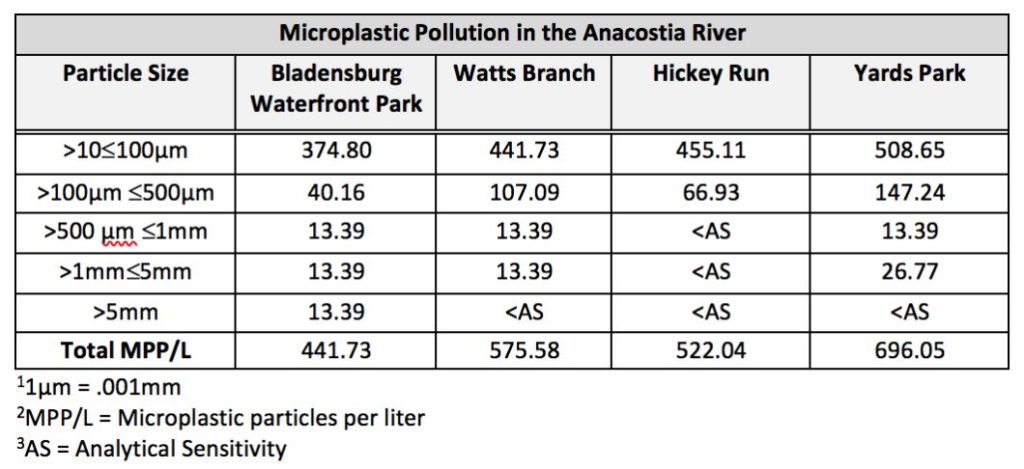

The Anacostia flows through a heavily urbanized watershed, so high levels of microplastics were, perhaps, to be expected. “We found up to almost 700 microplastic particles in one liter of water, at Yards Park,” says O’Donnell. The lowest level of plastics they found was at Bladensburg Waterfront Park, where there were about 440 particles per liter.

“People sometimes think it’s far away in the oceans or the Pacific garbage patch, when in reality, these microplastics are in our backyard, they’re right in the Anacostia River.”

Scientists are still studying the effect of microplastics on humans. But O’Donnell says it’s: “Probably not great.”

Plastics can be harmful for a variety of reasons. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, plastic bits ingested by fish, birds and other animals can cause digestive problems, impaired reproduction and even death. Plastic particles also contain additives that have been associated with cancer and endocrine disruption; and particles can accumulate contaminants including PCBs, PAHs and trace metals.

Microplastics come from a number of sources — a USGS study in the Great Lakes found that 70% of particles came from plastic fibers, from things like synthetic fabrics, diapers, tampons and cigarette filters. The next-largest category was made up from fragments — bits of broken up plastic litter, like bottles and cups — accounting for 16% of particles.

In 2015, Congress passed a law targeting microplastics, the Microbead-Free Waters Act, banning microplastics from being used in cosmetics. (No more exfoliating soap filled with little pieces of plastic!) But the law may not make a big dent. According the the USGS study, which was published before the ban went into effect, microbeads comprised just 1.6% of plastic particles in the Great Lakes, so most of the microplastic pollution would be unaffected by the microbead ban.

Robbie O’Donnell of Anacostia Riverkeeper says the levels found in the Anacostia were pretty high compared to other rivers, although not the highest. One study found the Thames in London had just 80 particles per liter (compared to 440 to 700 in the Anacostia), while another, similarly named British river, the Tame, near Manchester, had more than 1,000 particles per liter.

Use the online HTML editor tools to compose the content for your website easily.

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston