For Katherine Ott, public discourse about the 1969 Stonewall uprising tends to take place within a bit of an “echo chamber.”

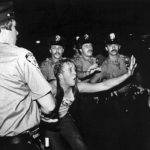

The Smithsonian curator is behind Illegal to Be You: Gay History Beyond Stonewall at the National Museum of American History. She regards herself as a “skeptic” when it comes to the way people talk about the nearly week-long series of riots and demonstrations at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village that began June 28, 1969, ignited by a police raid.

“There’s this mythology around it being the birth of the modern-day rights movement and how important and elemental it was,” Ott says. “I wanted to circumvent that and try to show there’s actually a lot more that happened before and has happened since.”

To that end, the exhibit, which opened June 21, references the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising as a conversation starter rather than a focus. The collection is a compact but impactful look at artifacts from several decades of LGBTQ history. Here, you’ll find the type of lobotomy knife used in gay-“curing” surgeries, a 1955 issue of gay rights publication the Mattachine Review, and Maybelline eye pencils that writer/director John Waters used to enhance his mustache.

As viewers approach the exhibit—which, apart from a nearby pillar wrapped in an image of activists, is limited to one display case—they’re met with four caution-yellow text trails affixed to the floor that read, “How far will you go to express who you are?”

“The only thing we all share is that it’s a risk to be different,” says Ott. “We look at three or four ways in which that has meaning.”

A very different treatment of Stonewall’s legacy is on display a half-mile down the road. Rise Up: Stonewall and the LGBTQ Rights Movement opened in March at the Newseum and presents an expansive look at modern LGBTQ history, seen from the vantage points of pop culture, public demonstrations, queer media, the AIDS epidemic, marriage equality, legislative history and more. Where the Smithsonian’s focus is fairly narrow, the Newseum’s is remarkably broad.

Exhibit writer Christy Wallover says the history of the LGBTQ rights movement dovetails with the museum’s mission to “champion” the First Amendment. “We wanted to make this exhibit about personal stories and how everyday Americans use their First Amendment rights to correct inequalities in society and exercise their freedoms,” Wallover says.

Visitors could easily spend an hour-plus with Rise Up, which is segmented into three discrete spaces and stuffed with artifacts (some from the Smithsonian’s archive) such as the red dress Sen. Tammy Baldwin wore to her 1993 swearing-in ceremony in the Wisconsin State Assemblyand the sewing machineGilbert Baker used to sew the first rainbow pride flag. The exhibit also incorporates three original videos, including one with frank stories from a wide swath of Americans.

With both exhibits, it’s these moments of connection with one person or one story that are among the most affecting.

In Illegal to Be You, a small, red Superman cape drapes a toddler-size mannequin. At first glance, it seems a bit out of place, seemingly an ordinary children’s Halloween costume—yet a nearby placard explains it once belonged to Matthew Shepard, the gay University of Wyoming student whose 1998 murder ultimately spurred hate-crime legislation.

Shepard’s parents, Ott says, had been communicating with the Smithsonian for a couple of years about donating some of their son’s belongings. And last October, the month Shepard’s ashes were interred at Washington National Cathedral, they gave the institution several items, including the cape and a wedding band Shepard had purchased for future nuptials (also appearing in the exhibit).

Two prior showcases at the National Museum of American History commemorated Stonewall (for the 25th and 40th anniversaries), but none were of this scope, Ott says. With Illegal to Be You, she anticipates some public criticism, even possible graffiti.

In comment books from one of the past exhibits, she recalls finding statements like: “This is sick.” “This is disgusting.”“You’re an abomination.” “You should all be killed.” Yet she’s also found comments from visitors who felt validated or were brought to tears.

“We want queer people who come to know this is their museum as well,” says Ott. “And we understand their history and they’re valued and a part of this country.”

Eliza Tebo

Eliza Tebo