Bartholdi Park isn’t exactly hidden. Located at a busy intersection next to the Botanic Garden (which is celebrating its bicentennial this coming year) and mere steps from the U.S. Capitol, it’s got prime real estate. And that’s kinda the point. This 86-year-old, two-acre park that’s part of the U.S. Botanic Garden (which, itself, is under the Architect of the Capitol) has long been a place where anyone can come for a moment of respite, be it marveling a beautiful succulent or strolling around in the middle of the night.

“I’ve been told by many who work on Capitol Hill that [when they’re] really stressed out, they go into Bartholdi Park, sit on one of the benches, see the fountain, and smell the plants,” says Holly Shimizu, former executive director of US Botanic Garden from 2000 to 2014, “They get some peace of mind. It really made my day when people told me that.”

Even on a recent cold November morning, the park still brims with flowering shrubs, green-leafed plants, and specks of color. It also holds several surprises, says the Botanic Garden’s horticulturist Ray Mims, who managed the park’s 2016 redesign. Strolling through, we see several of its 10 rain gardens, a sunken area that recycles rainwater to grow plants and flowers. The largest holds a hearty collection of carnivorous plants, including the white-topped pitcher plant that snacks on wasps. In the park’s southeast corner, there’s a Georgia-native Franklinia alatamaha (yes, named after Ben Franklin) that went extinct in the wild in the early 1800s. There’s a kitchen garden with leafy kale, a paw-paw tree that bears fruit every fall, and what are believed to be the northern-most consistently fruiting pomegranate tree in the country. When asked if people often pick these yellow-crowned treats, Devin Dotson, head of the US Botanic Garden’s public programs and exhibits, sighs. “They do. But they shouldn’t!”

Mims clarifies, “They’re actually federal property.”

In 1820, Congress approved a charter for the establishment of a “national greenhouse” that, in the words of the appropriately-named navy surgeon Edward Cutbush, was to be a place “where various seeds and plants could be cultivated, and, as they multiplied, distributed to other parts of the Union.” Originally on the Capitol Grounds, the Botanic Garden moved to its current location on Independence Ave and into the Lord & Burnham-designed greenhouse (a company that’s still around today) in 1933.

It was then that, next door to the greenhouse, a park was established. While the Botanic Garden is a museum of plants, Bartholdi Park is meant to show American landscaping has changed over time. “It’s always been this place that’s been centered on trends in horticulture,” says Devin Dotson, head of the US Botanic Garden’s public programs and exhibits. Those trends, of course, have shifted through the decades, from the early 20th-century focus on heavy trees and shrubs to the 1970s annuals trend. Today, using 2015’s Sustainable Sites Initiative as a guide, the park is a sustainable landscape using native plants that are designed to require minimal maintenance. “The park showcases the [kind] of sustainable landscape that people could have at home,” says Mims.

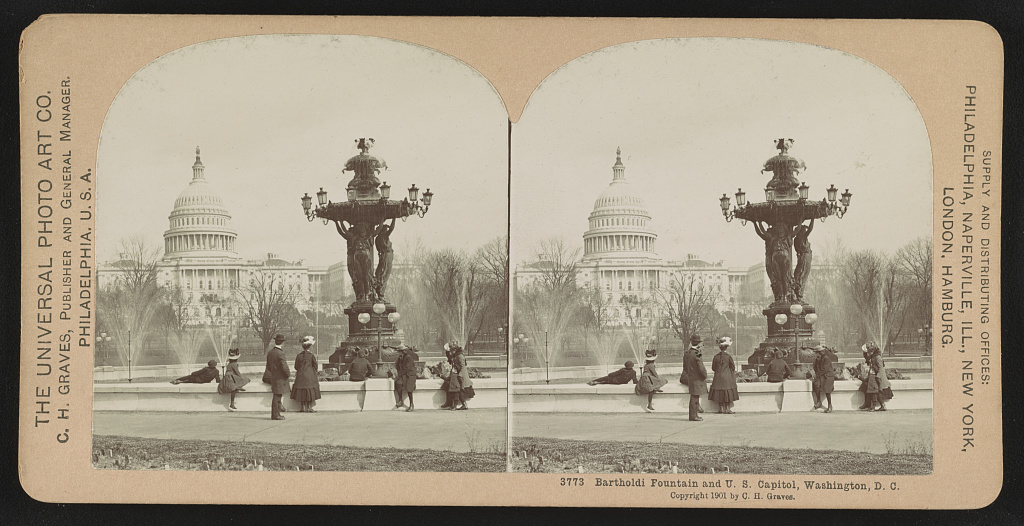

But the park’s namesake and centerpiece isn’t a plant or tree, but something very much human-made: a 15-ton cast-iron ornate fountain sculpted by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the same artist responsible for the Statue of Liberty.

In 1876, 140 miles north of D.C., the Centennial Exposition was held in Philadelphia to mark the hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Millions came from across the world to marvel at massive steam engines, try Heinz ketchup, and make calls on Alexander Graham Bell’s miraculous new invention. They also came to see (and climb) the work of French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, particularly a giant copper torch that would become iconic elements of the Statue of Liberty.

Also among the Bartholdi’s work in Philadelphia was an elaborate, bronze-painted, gas-lamp-lit, 30-foot-high, extraordinarily heavy fountain that he dubbed the “Fountain of Light and Water.” Believing that it symbolized a modern city with all of its iron, light, and water, he hoped to sell duplicates in order to help finance the completion of the Statue of Liberty. Unfortunately, American buyers weren’t very interested. “His intent was to put [copies] of the fountain in cities around America,” says Shimizu, “But it didn’t sell.”

That is, until famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who was redesigning the Capitol Grounds back in D.C. at the time, got involved. He wrote a letter to the Architect of the Capitol requesting the purchase of the fountain for the grounds. Congress struck a deal with Bartholdi: The American government paid six thousand dollars for the fountain, which was about half of its estimated value. After the Expo, the fountain was moved to the National Mall as the Botanic Garden’s centerpiece.

It instantly became a landmark in the city. The fountain is made of three tiers and ornate carvings featuring sea nymphs, spouting fish, and young seaweed-holding tritons (fish-tailed sea gods). At the base, there are several ominous-looking turtle creatures spraying water. On the second tier, there are 12 lamps that were all originally gas-lit. In 1915, the gas lamps were modernized with the addition of electricity, which made it a happening place even in the dark. Newspapers from that era talk about how it’s a must-visit and how it was a beloved spot for veterans. “It was one of the first places [in D.C.] that was consistently well lit at night for a safe gathering spot,” says Dotson, “It was a place to see and be seen.”

When the Botanic Garden was moved about a half-mile away to the intersection of Independence and Maryland Avenues, the fountain (renamed in honor of its creator, Bartholdi) came along and became the main attraction of the park. Over the years, the Bartholdi Fountain continued to marvel visitors, but it was tough to maintain. “An enormous fountain like that, it’s a lot to take care of,” says Shimizu, “Every aspect of it needs to be watched.”

In 2008, it became clear to Shimizu, who was the Botanic Garden’s executive director at the time, that the fountain was in desperate need of repairs. “If you looked at the fountain, it might seem okay,” she says. “But going inside, you could see the deterioration, the rust, the electrical [issues], and the decay.” The fountain also wasn’t completely level, an issue that had likely arisen over decades. “The water wasn’t falling equally from all sides. It’s a very precise requirement for a fountain with water [to]… be 100 percent level,” says Shimizu, “It’s the distribution factor, but it also has to fall evenly to capture the beauty.”

Over the next three years and at the cost of $580,000, the Bartholdi Fountain underwent major work to ensure that it would be preserved for another century. With the help of Robinson Iron, an Alabama company known for iron restoration work, the fountain was refreshed and re-wired, and the rust was removed. It also got a new base. Shimizu says the goal wasn’t to make the fountain look brand new, but fix it so would remain standing.“We did not want this to look like a shiny new black car. We wanted it to look old but refinished … to be timeless.”

The fountain’s renovation was nearly all done by August 2011, but something happened that could have undone all that work. “I was in the building in Bartholdi Park when I felt the earthquake,” says Shimizu, “The first thing I cared about was that fountain … I saw it going back and forth, swaying while [I was] having a minor heart attack.” But, much to her relief, it turned out to be totally fine. “It was due to good luck, good craftsmanship, and good construction.” The renovations were completed later that year.

Even as winter approaches and the with the fountain turned off, the park remains inviting with varied planet life, historic ironwork, and accessible nature. While there may be long lines for the Botanic Garden’s annual holiday display, Bartholdi Park is always open. “Bartholdi Park is open without walls and without doors,” says Dotson, “That’s the beauty of a public garden.”

Just don’t pick the pomegranates.

This story has been updated to clarify the relationship between Bartholdi Park and the U.S. Botanic Garden, and to correct the spelling of Frederic Law Olmsted’s name.

There’s No Paywall Here

DCist is supported by a community of members … readers just like you. So if you love the local news and stories you find here, don’t let it disappear!

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz