With its arched exterior, classical ornamentation, and vaulted, gilded ceiling, Union Station appears to be a Beaux Arts triumph, built to stand the test of time. You might not guess that the District’s stately transit hub is a bit of a scrappy survivor, having overcome the train station version of a midlife crisis as well as acts of Mother Nature—and acts of Congress. Thanks to a series of restorations and ongoing efforts to modernize and expand the terminal, the 112-year-old building is just getting primed for its next stage of life. Here are 10 facts you may not have known about Union Station

1. Architect Daniel Burnham designed Union Station as he led a massive project to redo the Mall.

Daniel Burnham, an architect with a knack for masterful urban planning projects, was tapped in 1901 to become the de facto head of the Senate Park Commission (aka the McMillan Commission, in honor of Sen. James McMillan of Michigan, who chaired the Senate Committee for the District of Columbia).

The commission’s overarching mission was to restore—and build upon—Charles L’Enfant’s original plan for the city. Part of the problem stemmed from the active Pennsylvania Railroad station, which had tracks on the Mall. There were two rail stations in the District, only blocks apart. The commission determined that to fulfill the vision of a grand expanse of trees and monuments extending West from the Capitol, the tracks must be removed and the rail lines consolidated. As the architects wrote in their 1902 report, the push to redesign the Mall meant “the opportunity is presented to Congress to secure not only the exclusion of the railroad, but also the construction of a union station, a consummation which, long agitated, has heretofore seemed beyond the possibility of accomplishment.” Congress seized the opportunity.

Union Station’s designers went for an ancient Roman vibe in their plans, drawing inspiration from the famous Baths of Diocletian and Caracalla as well as the Arch of Constantine. And, WETA explains, that the elaborate design “created a feeling of grandeur that reflected the economic power and prestige of the rail companies.” The symbolism of its design went even further, according to the National Park Service. NPS says it served to reflect the growing importance of the United States and its neoclassical elements “connected Washington to Athens and Rome,” two ancient centers of civilization. That connection was continued through Burnham’s master plan for the Mall, with the stately Lincoln Monument, the Memorial Bridge, and other buildings.

Union Station opened in 1907 to great acclaim. A Washington Post article from Oct. 27 of that year declared that “Washington can now receive and handle without confusion as great a crowd as could be handled in any city in the world.”

2. The site chosen for Union Station was known as Swampoodle, a neighborhood created by Irish immigrants.

The decision to plant Union Station was made to construct it smack-dab in the middle of Swampoodle, a neighborhood populated by Irish immigrants. It was also the home of Swampoodle Grounds, the baseball stadium where the Washington Nationals played from 1886 to 1889.

It was not among the ritzier neighborhoods in the District. Ghosts of DC describes it as a “nasty shantytown, rife with crime, rampant prostitution, and drunkenness.” Kathleen Lane, volunteer tour guide for Cultural Tourism DC whose great-grandparents lived there, told WAMU in 2011 that “it was considered at the time to be a very down at the heels slum, complete with goats and peoples’ laundry hanging over the wash. And it was really considered kind of shameful so close to the Capitol building.”

So where exactly did the name “Swampoodle” come from? A Post article from 1983 explained that a reporter is credited with naming the neighborhood in 1859, having described the area as “dotted with ‘swamps and puddles.” The modified name of ‘Swampoodle’ stuck.”

Nearly 100 homes were torn down to make room for the station, and the neighborhood faded from local memory. But it is having something of a revival in the form of a new public playground and dog park in NoMa, which opened last year. Neighborhood residents got the chance to vote on on the name, and Swampoodle won in a landslide.

3. A runaway train smashed into the concourse in 1953 and fell through the floor, landing partially in the basement.

The Federal Express, an overnight train bound for Washington from Boston, was barreling southbound from Baltimore on Jan. 15, 1953, when its conductor discovered he had an issue with the air brakes. Two miles out from Union Station, he began signaling ahead that the train would be unable to stop. The station employee watching the tracks was able to send a warning to evacuate bystanders and the stationmaster’s office ahead of the runaway train, as Ghosts of DC recounts. A later Baltimore Sun article detailed how the conductor ran through the train cars, yelling at passengers: “Get down on the floor! Lie down in your seat!” The train slammed into the building and plunged through the floor.

It wasn’t readily apparent to all passengers aboard what had just happened. A Boston Globe reporter, Frances Burns, was on the ill-fated train, and recounted her experience in an article in the Evening Star that same day: “A jolt threw me over against the door. I thought, ‘What bad engine driving!’” But perhaps the most remarkable part of Burns’ account came at the end, when she described witnessing a fellow female passenger on the Federal Express, who was demanding her baggage from an employee: “She said, ‘I can’t help what happened. It’s all your fault. I want my baggage. This is no way to run a railroad.’ He told her, ‘I’m sorry, you’ll just have to wait.’”

The accident injured more than 49 people, but “miraculously, no one was killed,” the Washington Post reported the next day.

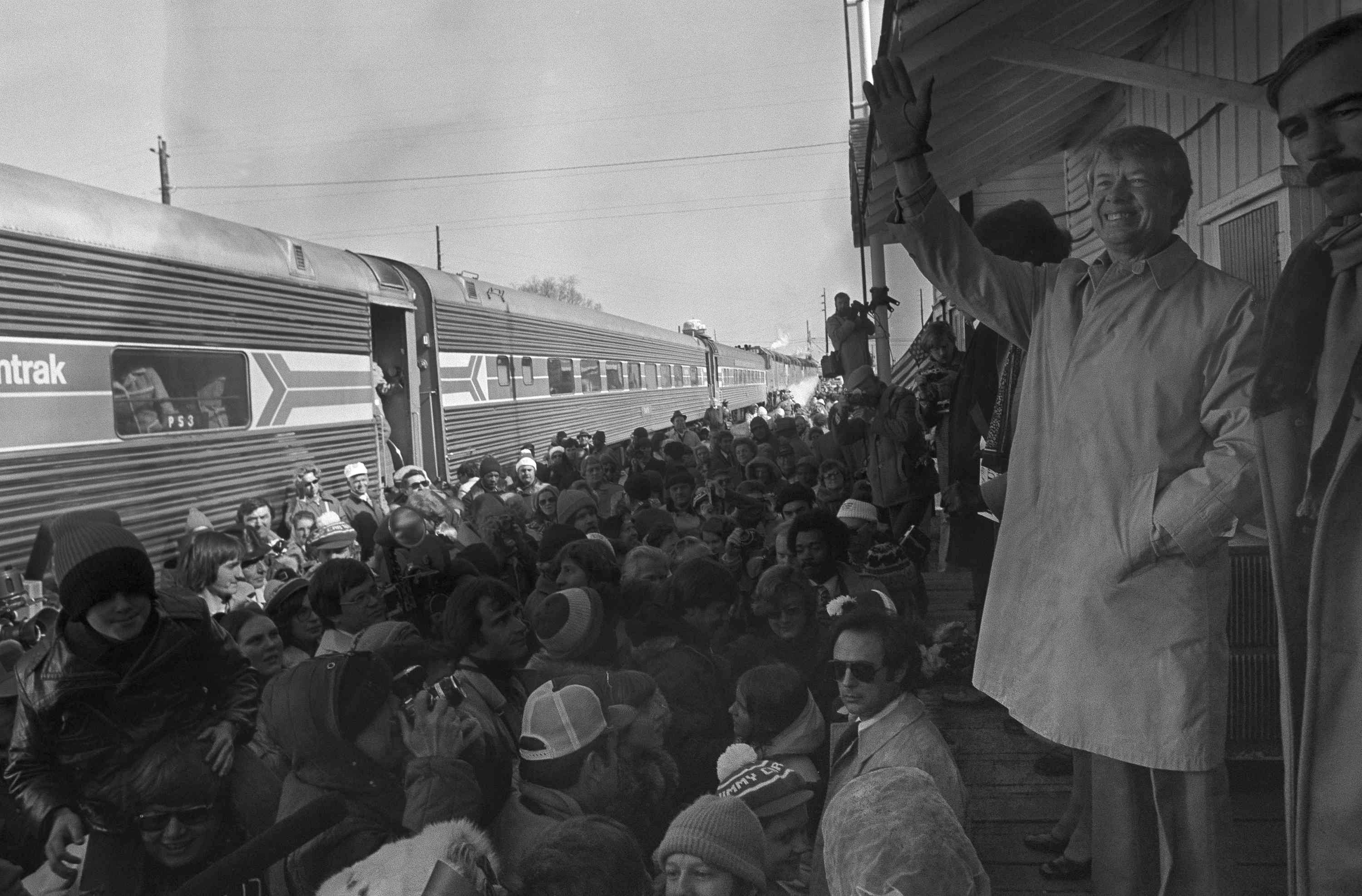

4. The Peanut Special, a chartered train, carried supporters of Jimmy Carter to Union Station in 1977 for his inauguration.

In 1977, President-elect Jimmy Carter’s campaign coordinated a special Amtrak ride to bring supporters to Washington for his inauguration. It was dubbed the “Peanut Special,” and it began its route at the Plains Depot in Plains, Ga., which had been shuttered to passenger travel in 1955 but reopened in 1976 as Carter’s campaign headquarters. (The depot is now part of the Jimmy Carter National Historic Site, managed by the National Park Service.)

The charter cost $80,000, according to an Amtrak history blog. Passengers could enjoy a dinner menu that paid homage to Carter’s southern heritage, featuring peanut soup, Georgia ham, fried chicken, and peach fritters. An internal Amtrak newsletter from February 1977 detailed that about 350 supporters, 30 staff, and 35 reporters rode the Peanut Special, and that the “atmosphere on board was dominated by large quantities of refreshments, mostly liquid, plus peanut tie tacks, peanut balloons, peanut necklaces, and other peanut souvenirs.”

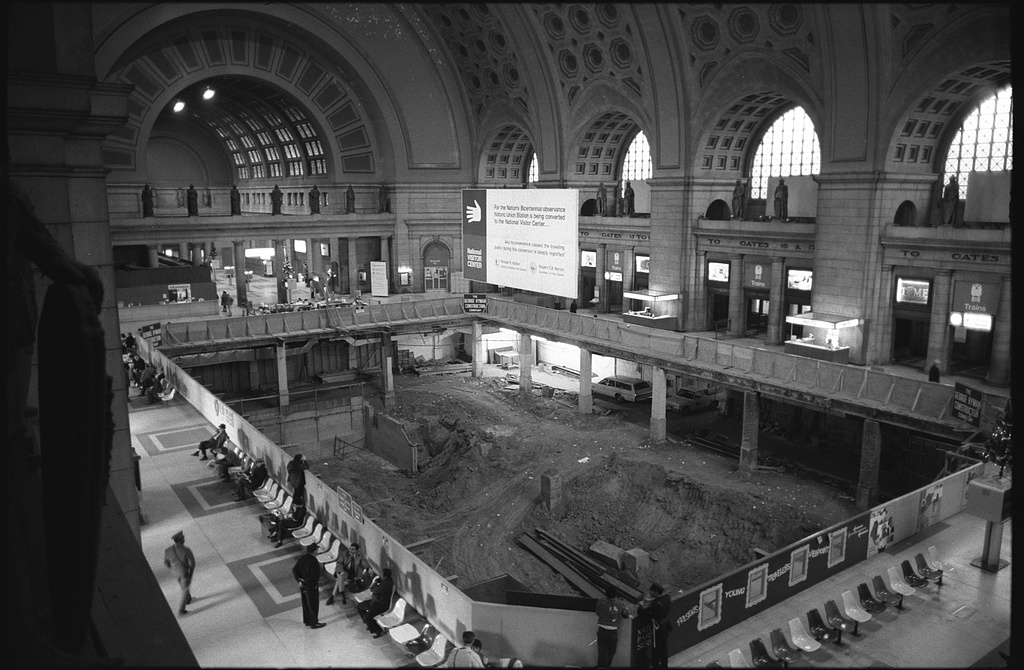

5. Union Station was repurposed as the “National Visitor Center” ahead of the bicentennial. It was a flop.

Ridership hit its peak during World War II, when as many as 200,000 people transited through Union Station each day, but it saw a steady decline in the wake of the war. As train ridership began to fall, Union Station began sinking into a state of disrepair and it was at risk of being demolished. But in the 1960s, planners dreamed up a new purpose for the aging transit hub ahead of the expected leap in tourists around America’s bicentennial celebration: a National Visitor Center.

President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Visitor Center Facilities Act on March 12, 1968, declaring: “The tourist and the student are invited to Washington. Then they are told to go and fend for themselves. It is as if we asked someone to come to our house to visit with us and then we told him to find the kitchen and fix his own dinner. The bill that I am signing here will assure that in the future our visitors to Washington will at least be given a proper welcome.”

The government leased the station from its railway owners and poured millions of dollars into the project. The floor of the main hall was torn out to develop a recessed theater for slideshows. But the center wasn’t fully completed when it opened on July 4, 1976, and it never saw many visitors.

A 1977 GAO report decried the many missteps in the whole affair, including that Congress was not informed of expensive changes in plans until it was too late to pursue alternative options; the emergence of questionable contracts; and that the federal government had not planned to pay for the construction of the project, only its lease. The report estimated that the costs to complete the center ranged from $115 million to $180 million, and noted that major structural, mechanical, and electrical issues required corrective action.

6. After its roof leaked, Congress passed a rehab bill in 1981 and later founded a nonprofit to manage its redevelopment.

In February 1981, the station’s situation had reached a critical mass. The state of the terminal was egregious, and the National Park Service declared the building unsafe. It closed it to the public after rain poured through the ceiling, leaving train passengers to trek around the eyesore to access the Amtrak station just behind it.

“Inside the ruined structure, mushrooms sprouted from the floor, and hordes of rats roamed instead of travelers,” a WETA blog described. It was “a national disgrace,” as a Washington Post article from April 4, 1981 quoted Richard R. Hite, the principal deputy assistant secretary of the interior for policy and the man who had been the department’s chief manager of the visitor center project. Hite was among the officials who went to bat for the terminal, proposing to spend at least $48 million to rehab the building.

Just a few months later, President Ronald Reagan signed the Union Station Redevelopment Act on Dec. 29, 1981. The bill laid the groundwork for the building’s revival. It also enabled the formation of the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation, a nonprofit organization that exists to restore, preserve, and maintain the station as a transit hub for years to come.

Five years later, the building reopened to passenger travel, complete with a shopping mall, a movie theater, plenty of dining options, and “restored down to the tiniest cornice and curlicue as it was at its opening in 1907,” a Post article described at the time. The refurbishment, which cost about $181 million, also finally added a large parking garage, something that had been pursued unsuccessfully for years before the station closed. It also added a central terminal for buses.

7. That’s not gold paint on the ceiling. It’s real 23-karat gilding.

After a magnitude-5.8 earthquake jostled the District in August 2011, Union Station was among the building casualties in need of repair. DCist reported in 2014 on the repair efforts, which included reinforcing the 96-foot-tall plaster ceiling and regilding its 255 octagonal coffers.

A $350,000 grant from American Express and the National Trust for Historic Preservation helped pay for the project, which required more than 120,000 sheets of gold leaf.

The leafing was imported from Italy. As Architect Magazine explained, metallurgists determined that, by upgrading the existing gold leaf to 23-karat, the lifespan of the gilding could be doubled, to last more than 75 years. (The previous gold leaf had been 22-karat, which has a lifespan of about 35 years—it had been installed in the 1980s when the station was renovated.)

8. There’s a presidential suite, and you can rent it out.

The presidential suite on the building’s far east side was designed in the wake of the assassination of President James Garfield to give presidents and other dignitaries a safe place to wait for their trains. Garfield had been fatally shot at one of Union Station’s predecessors, the Baltimore and Potomac rail station, as he was rushing to catch his train in 1881. (The site of that rail station is now home to the National Gallery of Art’s West Building. There is a marker at the spot, which was placed in 2018 after efforts by the James A. Garfield National Historic Site and the National Park Service.)

The space was later converted into a USO lounge during World War II, when Union Station saw as many as 200,000 people transiting through it daily. Now, it serves as an event space that is available to rent out (along with the Main Hall, East Hall, and Columbus Club, which is located on the second floor). Union Station itself has been the site of inaugural balls and other large events.

9. Amtrak has huge plans for Union Station: tripling the passenger capacity and doubling train capacity in the next 20 years.

Amtrak has dubbed its initiative to modernize and expand the 112-year-old station’s capacity the “2nd Century Plan.” The estimated $7 billion plan, which grew out of Amtrak’s 2012 Master Plan for the station, calls for new, wider train platforms, new below-track concourses, and a new bus facility. It also includes an urban mixed-use development called “Burnham Place,” in a nod to Daniel Burnham, to be built above the rail yard.

It’s part of an ongoing effort to improve the station, which, at the southern terminus of the busy Northeast Corridor, is Amtrak’s second busiest station. (New York leads the pack, according to Amtrak data.)

A concourse makeover, which will alleviate congestion, add more natural light, and construct a new, 10,000-square-foot luxury lounge, is also in the works and expected to be completed by 2022. The billions of dollars in funding for the 2nd Century plan, though, has yet to be secured. A July 2018 report from the company’s Inspector General said that Amtrak’s nine improvement projects at Union Station “face risks of delays and cost overruns due to weaknesses in their scheduling, cost estimating, and project management practices.”

In August, Amtrak unveiled a new boarding procedure, in an effort to streamline a process that was often a source of passenger complaints. (Amtrak itself is no stranger to criticism about boarding procedures, as a 2016 Inspector General report outlined ways to improve the passenger experience.) In September, Amtrak unveiled new nonstop service between Union Station and New York, and is modernizing its fleet of Acela trains.

10. A proposed protected bike lane on Louisiana Avenue would connect Union Station to Pennsylvania Avenue NW, but Congress has to approve it.

The lane would serve as an important link to the city’s bike lane infrastructure, connecting the Pennsylvania Avenue Cycle Track and the Metropolitan Branch Trail. It’s a route that the Washington Area Bicyclists Association has said is necessary for cyclists’ safety. The group wrote in a 2015 blog post that “it is exceedingly difficult today for even the most experienced bicyclist to travel the short distance between these two hubs without unacceptably elevated risk.”

Efforts to build the lane have been in the works for years, but progress has been cumbersome for several reasons. As DCist reported in 2018, D.C. Department of Transportation would normally draw up a plan, seek community input, adjust and present a preferred plan, and then fund and construct it. However, Louisiana Avenue isn’t your typical District road: It was carved out on Capitol grounds when Union Station was constructed, and therefore that stretch of road is owned by the Architect of the Capitol—meaning Congress has the final say.

Once the Architect of the Capitol signs off on the plan, then it moves to a vote from the Senate Rules Committee and the House Office Building Commission. But the Architect of the Capitol has put conditions on its support for a bike lane plan that include retaining as many of the nearly 40 curbside parking spaces on Louisiana Avenue as possible.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District’s non-voting representative to Congress, has been a staunch supporter of the protected bike lane. In a 2018 letter, she urged then-Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Frank Larkin to reconsider his opposition to the bike lane, calling the loss of a few parking spaces “a small price to pay to ensure public safety and help alleviate congestion.” And not all members of Congress are opposed to the project: The Washington Post reported earlier this year that the Congressional Bike Caucus, a group of more 130 lawmakers, supports the plan.

Previously:

10 Facts You May Not Know About National Airport

10 Facts You May Not Know About Friendship Heights

10 Facts You May Not Know About Takoma

10 Facts You May Not Know About Columbia Heights

10 Facts You May Not Know About Petworth

10 Facts You May Not Know About Chinatown

10 Facts You May Not Know About Spring Valley

10 Facts You May Not Know About Navy Yard

10 Facts You May Not Know About Brookland

10 Facts You May Not Know About Anacostia

10 Facts You May Not Know About Dupont Circle

Nine Facts You May Not Know About The Southwest Waterfront

There’s No Paywall Here

DCist is supported by a community of members … readers just like you. So if you love the local news and stories you find here, don’t let it disappear!