A granite building with a golden torch topping its dome, the Library of Congress is tucked just to the east of the Capitol. Its ornate “gingerbread exterior” (as FDR reportedly once described it) and elaborately decorated interior are meant to celebrate the many rich literary treasures found inside. The world’s largest library (which is actually spread across several buildings) likely has a vast trove of facts you probably didn’t know, but here are 10 highlights.

1. The library actually was created to provide books solely for the use of Congress

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams signed a law to provide $5,000 in appropriations to acquire books for the use of members of Congress. (Here’s a sampling of the original purchases.)

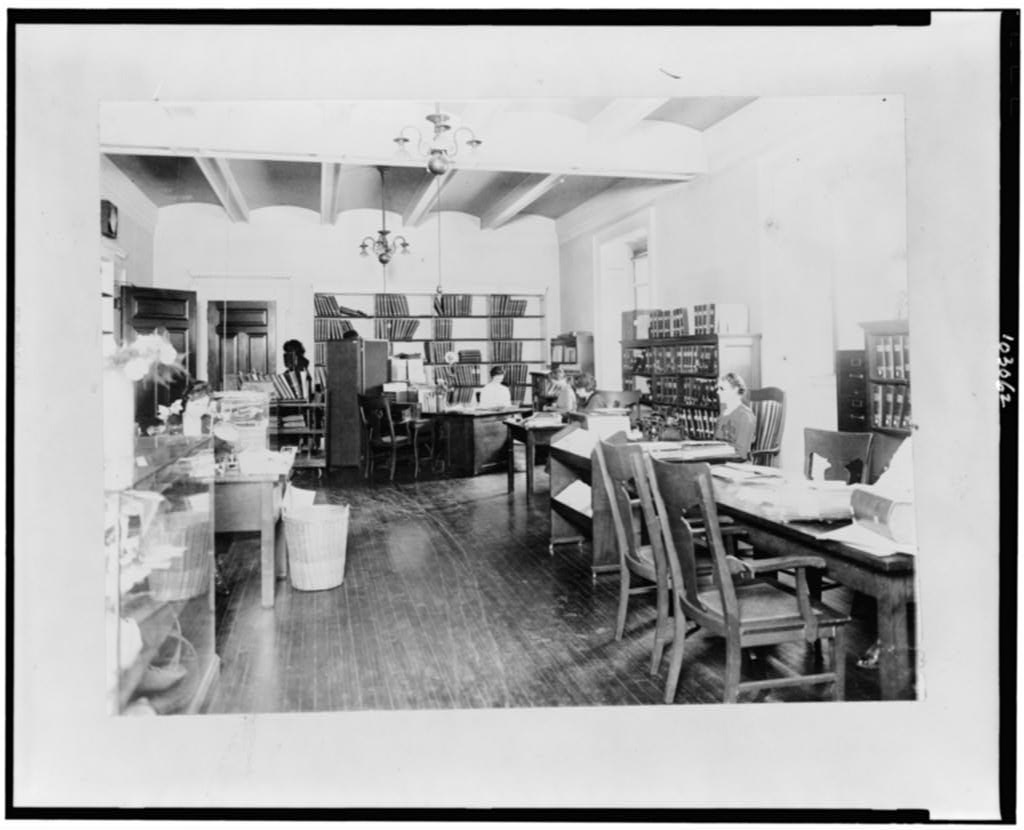

The library was originally housed in a spacious central room in the Capitol. A plaque now marks the approximate location of the first library. (It also states grimly that “the books in the library were used to kindle the flames that destroyed this section of the building” in the War of 1812.) In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson signed a bill into law that widened library privileges to the president and vice president (and the rest of the executive branch). Still, the law specified that “no map shall be permitted to be taken out of the said library by any person; nor any book, except by the President and Vice President of the United States, and members of the Senate and House of Representatives, for the time being.” Use of the library eventually expanded beyond government officials and their families. Technically, according to Library of Congress historian John Cole, public access to the library had been permitted as early as the 1830s, because it was in a publicly accessible building, but it wasn’t until the opening of reading rooms in the new building in 1897 that the library officially began publicizing access to materials.

2. After the War of 1812 decimated the library’s original collection, Thomas Jefferson let Congress name its price to purchase his private library

The warring Brits may have taken advantage of the massive fire hazard that a large room full of books posed ehen they set fire to the unfinished building on Aug. 24, 1814, much of the Capitol was destroyed along with most of the library’s collection.

Thomas Jefferson was so stricken by the loss of the library that he offered the sale of his personal library to replace the books, saying in a letter dated Sep. 21, 1814, to Samuel H. Smith: “I have been 50. years making it, & have spared no pains, opportunity or expence to make it what it is.” So extensive was his collection that Jefferson estimated “18. or 20. waggons would place it in Washington in a single trip of a fortnight.”(The actual plan was that 10 wagons, which could carry 2,500 pounds each, would transport the library.)

Jefferson did not name his price, choosing to allow Congress to determine what it would pay him for his offerings. Congress accepted, and set a price of $23,950 for the 6,487 volumes.

It wasn’t entirely without controversy, though. According to the National Archives, seventy-one Federalists opposed the purchase, objecting to “its extent, the cost of the purchase, the nature of the selection, embracing too many works in foreign languages, some of too philosophical a character, and some otherwise objectionable.” But on Jan. 30, 1815, President James Madison signed into law the bill authorizing the purchase. Jefferson himself inventoried and numbered his library.

3. Another fire, in 1851, ravaged the library’s collection, leading to the design of a fireproof cast iron room in the Capitol.

A faulty chimney flue took the blame for the devastating blaze on Christmas Eve in 1851 that burned more than half of the library’s 55,000-volume collection. An estimated 35,000 books — including nearly two-thirds of Jefferson’s library — were lost. That led Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter to design a new, fireproof cast-iron room in the Capitol’s west front for the library. It opened on August 23, 1853. (Walter also designed the Capitol’s cast iron dome.) The ironclad library was “widely admired” and drew plenty of tourists. That is, until it was dismantled in 1901 and its cast iron sold for scrap, according to a Roll Call story in 2017.

4. The library didn’t get its own, separate building until nearly 100 years after it was created.

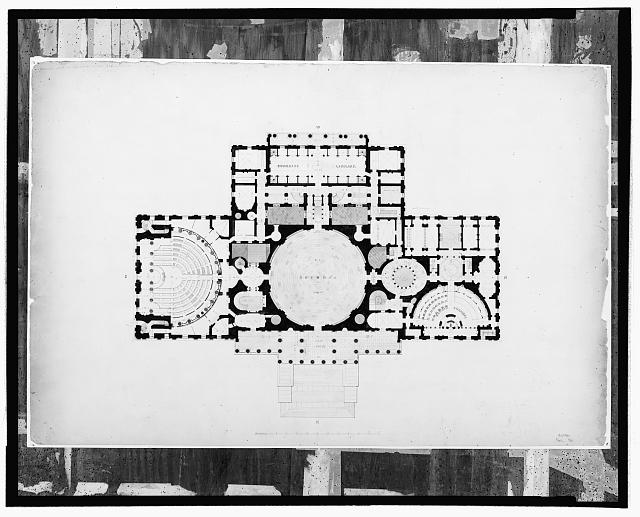

As the years went on, the books started piling up — literally. An 1884 Washington Post story described how “long years ago the shelves were filled; supplementary ones — necessarily of wood — have been introduced wherever possible; and books are piled in great heaps all over the floor, allowing scarce space for the library attendants to move from point to point.” Even so, some lawmakers were opposed the idea of building a separate building, no matter how badly the extra space was needed. The naysayers lost out, and a number of wild proposals were submitted in a design contest. One rejected idea was “to honeycomb the dome of the Capitol with bookstacks,” a 1937 guide to the city produced by the Works Progress Administration said. Other rejected designs are reminiscent of a cathedral or perhaps what the lovechild of the Capitol and the Eisenhower Executive Office Building would have looked like.

Congress selected a design submitted by John L. Smithmeyer and Paul J. Pelz that evoked the Paris Opera House.It cost roughly $6.5 million to build at the time, and it finally opened in 1897. (The 1937 guide sassily declared that “in its day the Library building was hailed as a masterpiece of architecture, but to the modern eye this celebrated monument of the Victorian era seems inexcusably overdone.”)

By the 1920s, however, the library was again in need of extra space. President Herbert Hoover signed a bill into law in 1930 to appropriate funding for the construction of what was originally dubbed the “Annex,” now the John Adams Building. It opened on Jan. 3, 1939, and according to the Architect of the Capitol, boasts 180 miles of shelving. .

Just about 20 years later, in 1960, Congress appropriated funding for a third building, which opened in 1980 and was called the James Madison Memorial Building, in honor of the fourth president and “father of the Constitution.” The AOC says the building is “the largest library structure in the world,” with 1.5 million square feet of space. It still wasn’t enough space: In 2007, a campus dedicated to audio-visual holdings in Culpeper, Va., was donated to the library.

5. The library completed an underground “rapid transit literary line” in 1895 to ferry books to and from the Capitol.

Even though the Library of Congress would be located just across the street, a tunnel was constructed and an electric conveyor system developed to easily send books back and forth to the Capitol. A Washington Post article on Sept. 13, 1895, described the new system: The tunnel, about 6 feet high and 4 feet wide (“so as easily to admit a man in case of any tie-up in the rapid transit literary line,” the article explained) ran about 1,100 feet. A so-called “car” could travel the distance in two or three minutes, and Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the Librarian of Congress at the time, told the Post that “a book can be received at the Capitol in five minutes after the order is sent from there to the library.” Requests for volumes were sent by pneumatic tubes. Later, the John Adams building was also connected to the main building by a pneumatic tube system, which enabled books to be placed in leather pouches and whisked across the street in an impressive 28 seconds. But as Atlas Obscura recounts, the original book tunnel was lost in the 2000s when precious subterranean space was needed for the underground Capitol Visitor Center.

6. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were housed in the library from the 1921 until 1952.

In September 1921, President Warren Harding issued an executive order to transfer the original copies of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the Library of Congress from the State Department. His executive order explained that the move came “at the request of the Secretary of State, who has no suitable place for the exhibition of these muniments and whose building is believed to be not as safe a depository as the Library of Congress” as well as “to satisfy the laudable wish of patriotic Americans” to see these important documents.

An article in the National Archives’ Prologue magazine in 2002 detailed the humble transfer: “The next day, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam went to the State Department, signed a receipt, placed the Declaration and Constitution on a pile of leather U.S. mail sacks and a cushion in a Model-T Ford truck, returned with them to the Library of Congress and placed them in a safe in his office.”

Congress appropriated $12,000 to create a special exhibit for the documents, which opened in 1924. It was the first time the Constitution had been placed on exhibit, according to Prologue. The exhibit was short-lived, however, as Congress began appropriating funding for the National Archives building. A tug-of-war over the documents nearly ensued when President Herbert Hoover declared in 1933 his intention to enshrine the two documents within the Archives after its completion. The Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, dug in, reportedly saying Hoover “made a mistake,” and the documents remained at the Library of Congress until they were sent to Fort Knox, Ky., for safekeeping in December 1941, as America entered into World War II.

The documents returned after the war, with a new exhibit at the Library of Congress, but the new Librarian of Congress, Luther Evans, and the new Archivist, Wayne Grover, met and quietly worked behind the scenes to transfer the documents for a display at the National Archives, along with the Bill of Rights.

Congress unanimously approved the transfer on April 30, 1952, according to a Washington Post article from the time. The transfer occurred in December of that year, and it would be a spectacle of “pomp, circumstance and security,” The Washington Post reported ahead of the move, with armored cars transporting the documents, escorted by tanks, armed guards and members of the military.

7. That’s real gold leaf on top of the “Flame of Knowledge.”

The building’s original design called for the copper dome and the Flame of Knowledge atop it to be covered in gold leaf. But, a history from the Library of Congress says, “weather and the chemical effects of the 19th century method of tinning the copper beneath the gold leaf dome combined to produce perforations in the copper” and a restoration undertaken in 1931 replaced the leaking copper dome with a new, ungilded one. The dome was allowed to acquire its patina to blend in better with its granite building. Fresh gold leaf was placed on the flame during a restoration effort in the 1980s. Another restoration project led to the removal of the original gilded “Flame” in 1996, and it was placed into the Architect of the Capitol’s archival warehouse on Fort Meade, Md., according to Atlas Obscura.

8. The position of the Librarian of Congress requires a presidential appointment.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson made the Librarian of Congress an appointed position (The Senate only began confirming the president’s choice of librarian in 1897.)

As a 1984 Library of Congress information bulletin explains, “presidents thus have a genuine opportunity to shape and influence the ‘Congressional’ library,” noting that Jefferson and the Roosevelts were among the chief executives who “greatly strengthened” the library’s national and cultural roles. Some librarians have held an especially significant impact on the library, too. Take Ainsworth Rand Spofford, the sixth Librarian of Congress, who was appointed to the post by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864. He successfully lobbied Rutherford B. Hayes, Chester Arthur, and Grover Cleveland to urge Congress to legislate and fund the library’s expansion.

Another notable Librarian of Congress, Archibald MacLeish, was the first non-librarian to be nominated to the position. President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose the lawyer-turned-writer, which a Politico story from 2015 says “raised hackles” with the American Library Association and some Republicans since MacLeish had been an expatriate in Paris in the 1920s and rumored to be a Communist sympathizer. His expatriate years resulted in him being well-connected with many of the literary greats of his era, including Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway wrote MacLeish a letter in 1943 to float the idea of his becoming “the accredited correspondent for the Library of Congress” in World War II, to write, as Hemingway put it, “not govt. publications or propaganda but so as to have something good written afterwards.” (Hemingway did not become the library’s war correspondent.) MacLeish, himself a poet who won three Pulitzer prizes, helped organize and restructure the library, and even had a formative role in helping shape what’s now known as the country’s Poet Laureate.)

The current Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden, is both the first woman and the first African American named to the position. At her swearing in as the 14thLibrarian of Congress on Sept. 14, 2016, Hayden said the “opportunity to serve and lead the institution that is the national symbol of knowledge is a historic moment,” DCist reported at the time. Under her leadership, the library in the midst of an ambitious five-year plan called “Enriching the Library Experience” to digitize its collection and make it accessible online, a.k.a. “throwing open the treasure chest, as we like to say,” Hayden told CNET in an interview in April 2019.

9. The library adds more than 10,000 items to its collection each working day.

You read that right: The library adds thousands of new items every working day (and receives 15,000 items every working day). But those number don’t just include books — nor is everything in English, as about half of its serial and book collections are in foreign languages. The library keeps audio materials, manuscripts, maps, microforms, sheet music, and photographs, to name a few. It also maintains the National Film Registry, which preserves such treasures as “The Big Lebowski,” “Jurassic Park,” and “The Sex Life of the Polyp” for future generations to come. It even collected public tweets for years, WAMU reported in 2017, but went on to note that as of Jan. 1, 2018, the library began acquiring tweets on “a very selective basis.”

10. Want to access the library’s vast trove? You just need a Reader Identification Card.

Anyone 16 and older with a Reader Identification Card may access the library, though some rooms require researchers to be at least 18. But it isn’t like a neighborhood library: visitors can’t remove items from the reading rooms or library buildings.

The card is valid for two years from its issue, and you can preregister for your card up to two weeks in advance online.

There’s No Paywall Here

DCist is supported by a community of members … readers just like you. So if you love the local news and stories you find here, don’t let it disappear!