More people are heading to grocery stores to fill their pantries in the event they have to stay home for long periods of time as the coronavirus spreads throughout the D.C. region. But for those who don’t have that ability, nonprofits and food banks are stepping up to help fill the void.

The Capital Area Food Bank has ordered an extra 34,000 pounds of food in anticipation of higher demand for food assistance. Part of that effort involves preparing contingency distribution plans so services can continue to reach some of the region’s most vulnerable populations.

“We do anticipate that there may be some supply chain disruptions … for certain members of our community, and so it might make food just that much harder to come by,” says Radha Muthiah, the food bank’s CEO. “We want to be prepared to provide them food when they need it.”

The additional order of both non-perishable and fresh foods by the region’s largest food assistance organization amounts to a week of meals — breakfast, lunch and dinner for seven days — for about 1,000 people.

[D.C. businesses and workers are bracing for the impact of coronavirus]

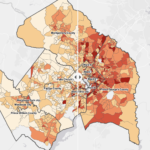

The group provides food directly to clients, and through its more than 450 community-based partners. It reaches more than 400,000 people in D.C., Virginia and Maryland, including more than 9,000 senior citizens. The areas of greatest need are Wards 7 and 8 in the District and Maryland’s Prince George’s County, according to the organization’s hunger heat map.

So far, Muthiah says, Capital Area Food Bank hasn’t had any problems procuring what it needs. Its main concern is the pipeline of food to its clients — many of whom are service industry workers who will be disproportionately affected if there is a prolonged economic downturn.

Things like the cancellation of conferences and decline in tourism means reduced paychecks — or no paycheck at all — for many who receive assistance, according to Muthiah.

As of now, the food bank — along with a number of other large groups like Martha’s Table, Bread for the City and Northern Virginia Family Service — has no plans to cancel upcoming markets or other distribution activities or services.

Meeting Basic Needs Remains ‘Top Priority’

Like other organizations, Northern Virginia Family Service plans to remain open as long as possible. The group provides a wide range of food, medical, legal and employment services to thousands of clients annually, mostly in Falls Church and Fairfax and Prince William counties. About 10,000 people — half of them children — receive food assistance through the organization.

“Our top priority is identifying creative and safe ways to continue to ensure the most basic needs (food and shelter) of the 42,000 people we serve each year can continue to be met,” said Stephanie Berkowitz, the group’s president and CEO in an email to WAMU.

The organization is looking at ways to deliver services remotely, like job coaching and housing counseling. Berkowitz says they are considering other options, such as purchasing phone minutes to low-cost digital devices for clients with the most pressing needs who don’t have internet connections.

“We are still early in this process and have innumerable considerations still in front us …while balancing the reality that we are in the midst of a public health crisis and need to respond accordingly,” Berkowitz said. “This becomes increasingly critical, as many of our clients have limited resources to withstand an extended crisis.”

Volunteers Are Canceling Amid Outbreak Fears

Radha Muthiah with the Capital Area Food Bank says volunteers are canceling their shifts just as the group needs more workers to help package and distribute the extra supplies.

In the past few days, at least four different groups have canceled plans to volunteer at the food bank’s warehouse. Even with about 120 staff members, 80 to 100 volunteers help out per day on an average week.

“That is a growing concern for us. We can manage it today, tomorrow. But it’s unclear how this will play out,” she says.

Muthiah says the group is planning ahead in case some of its partners — faith-based institutions, for instance — need to shut down or volunteers don’t feel comfortable coming out. It’s in the process of identifying several dozen partners with robust operations that can continue operating in the event of more widespread closures — all with an eye toward ensuring geographical reach and areas of high need. And in the worst-case scenario, Muthiah says they would work in conjunction with government emergency centers.

Going forward, it’s likely that more food will need to be pre-packaged and boxed, instead of picked out and purchased in market-like settings due to health concerns.

In that case, Muthiah says, “we will absolutely need more volunteers.”

Capital Area Food Bank’s community-based partners like Martha’s Table — which has locations in Northwest and Southeast D.C. — are already making similar moves, shifting to a pre-packaged, pre-bagged model of distributing food, and planning alternate ways of getting food to clients in the event of disruptions.

If schools close, for instance, Martha’s Table is making plans to get food to the more than 150 children enrolled in its education programs.

“We want people to know that we’re actually working to expand services at this time,” says Whitney Faison, the group’s associate communications director.

“Our mission is to continue to do what we are doing and also be there for folks who need us most right now,” Faison says.

This story first appeared on WAMU. Jenny Gathright contributed reporting.