By Monday, Ward 6 resident Alex Dickson was running out of options. She had requested an absentee ballot for the following day’s primary election, but even after repeated promises from the D.C. Board of Elections that one had been sent, she had yet to receive it.

By late that day, election officials offered her another option: She could vote by email. “What? OMG that’s crazy,” wrote Dickson in a Twitter exchange with an election official. But on Tuesday morning, that’s what she did.

Faced with what is reported to have been hundreds of complaints from D.C. residents who said they never got requested absentee ballots in the mail, early this week the elections board decided to offer the chance to cast their ballots via email, using an existing service that had been used in the past — but only for a small group of voters with disabilities, and also for those in the military living overseas.

The move came in the last-minute scramble to accommodate voters ahead of Tuesday’s primary, which was being conducted largely through the mail because of the COVID-19 pandemic. But the sudden shift in how the election was to be run — announced in late March, two months ahead of the primary — wasn’t without its challenges, leaving the elections board struggling to keep up with a huge number of requests for absentee ballots: more than 90,000 all told, roughly tenfold most normal election cycles.

Board staff troubleshot voter problems over the phone, email and even Twitter, hand-delivered ballots in limited cases and worked with D.C. councilmembers to ensure that voters got ballots they had requested. And in at least 500 cases, the board allowed voters to cast ballots over email.

But what could seem like the ultimate convenience in exercising a civic duty is actually fraught with possible complications and risks, so much so that many experts say any sort of email voting at scale is a dangerous idea.

“It’s definitely very high-risk from a security standpoint,” says Marian Schneider, the executive director of Verified Voting, which promotes accuracy and verifiability of elections. “There’s really nothing secure about sending a PDF off to an individual and having them send it back to the election office.”

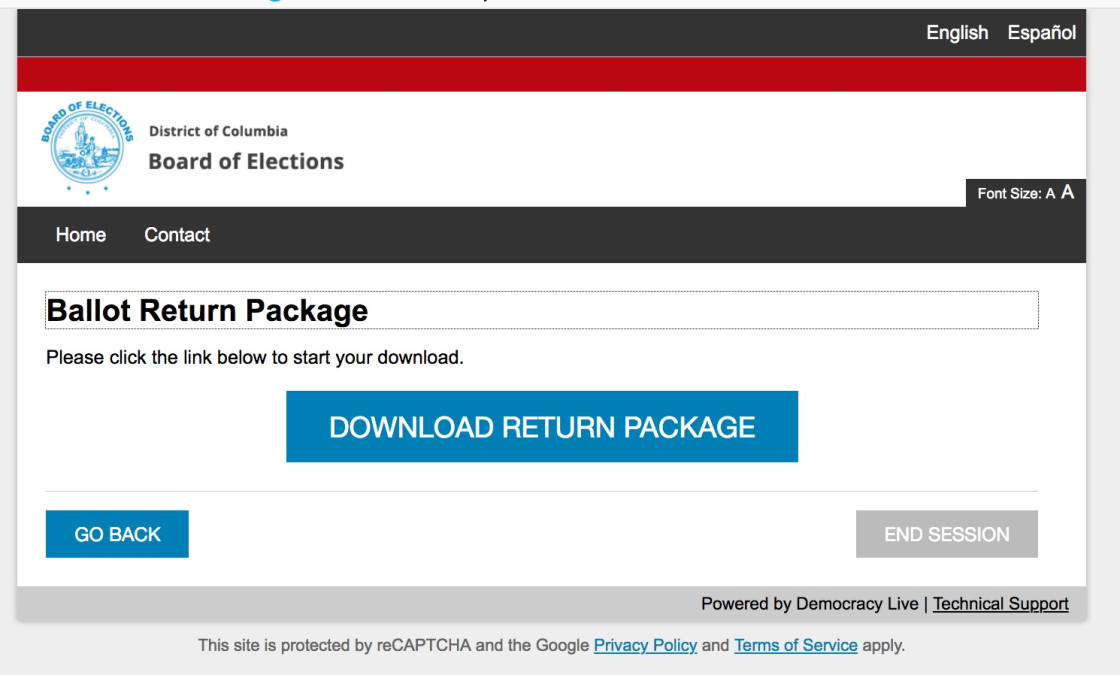

And that’s largely how D.C.’s system worked. The select voters allowed to vote by email were given a link where they could download their ballot. They could print it, fill it out and drop it in the mail — or send it back to the elections board as a saved or scanned PDF document. For security purposes, each voter had to verify their birthdate and sign an affidavit proving they were in fact who they said they were. (Alex Howard, another D.C. resident who voted by mail, shared his experience online.)

“The problem with an email transaction like this is it can be intercepted en route, altered, and then sent on its way. And the voter has no idea what the election office received. And the election officers don’t really have any idea that this is the voter’s true intent. So that’s the real problem with it,” says Schneider, who adds that various federal agencies have warned against email or electronic voting — which is available in a number of states.

And there’s another issue: People voting by email have to waive their right to privacy, meaning that their name could potentially be connected to the votes they cast. In instructions to voters, the D.C. elections board did say that names “will be permanently separated from my voted ballot to maintain its secrecy at the onset of the tabulation process and thereafter.”

The Board of Elections did not respond to a number of questions regarding how voters were chosen to cast ballots via email and what security protocols exist. But a decade ago it was one of the first places in the country to let hackers try and break into an online portal being tested for possible online voting for absentee ballots; they easily succeeded, scuttling any further consideration of the project.

“While understandable that they didn’t want voters to be disenfranchised… casting ballots via email should not be part of contingency plans,” tweeted Eddie Perez, a voting technology and election administration expert at the OSET Institute, which works to improve voting software.

All told, the number of D.C. voters who did actually vote by email was minimal; 500 out of more than 50,000 absentee ballots received so far. And in some cases, the option was all that was left for some voters. Ward 5 voter Patrice Sulton had requested an absentee ballot but never received it, and was in Wisconsin on the day of the primary so could not vote in person. She said the security issues did not concern her.

But for Alex Dickson, the process was eye-opening — and maybe not in a good way.

“The mail-in system has to work no matter what,” she says. “Not everyone is going to vote electronically — either because of skill level or internet access — and everyone should have the right to cast a ballot they way they want to, not the way the board decides they should.”

Looking ahead to November’s general election, Alex Howard wrote that while he was concerned with privacy and security, voting by email might have to be an option that’s offered to more people.

“It seems to have worked — for me,” he wrote. “But offering ‘vote by email’ to all would be risky at scale and require new investments in personnel, technology, and public engagement. If the pandemic is raging this fall, it might be necessary for the Council of D.C. to make them.”

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle