This post was last updated at 2:20 a.m. on June 8.

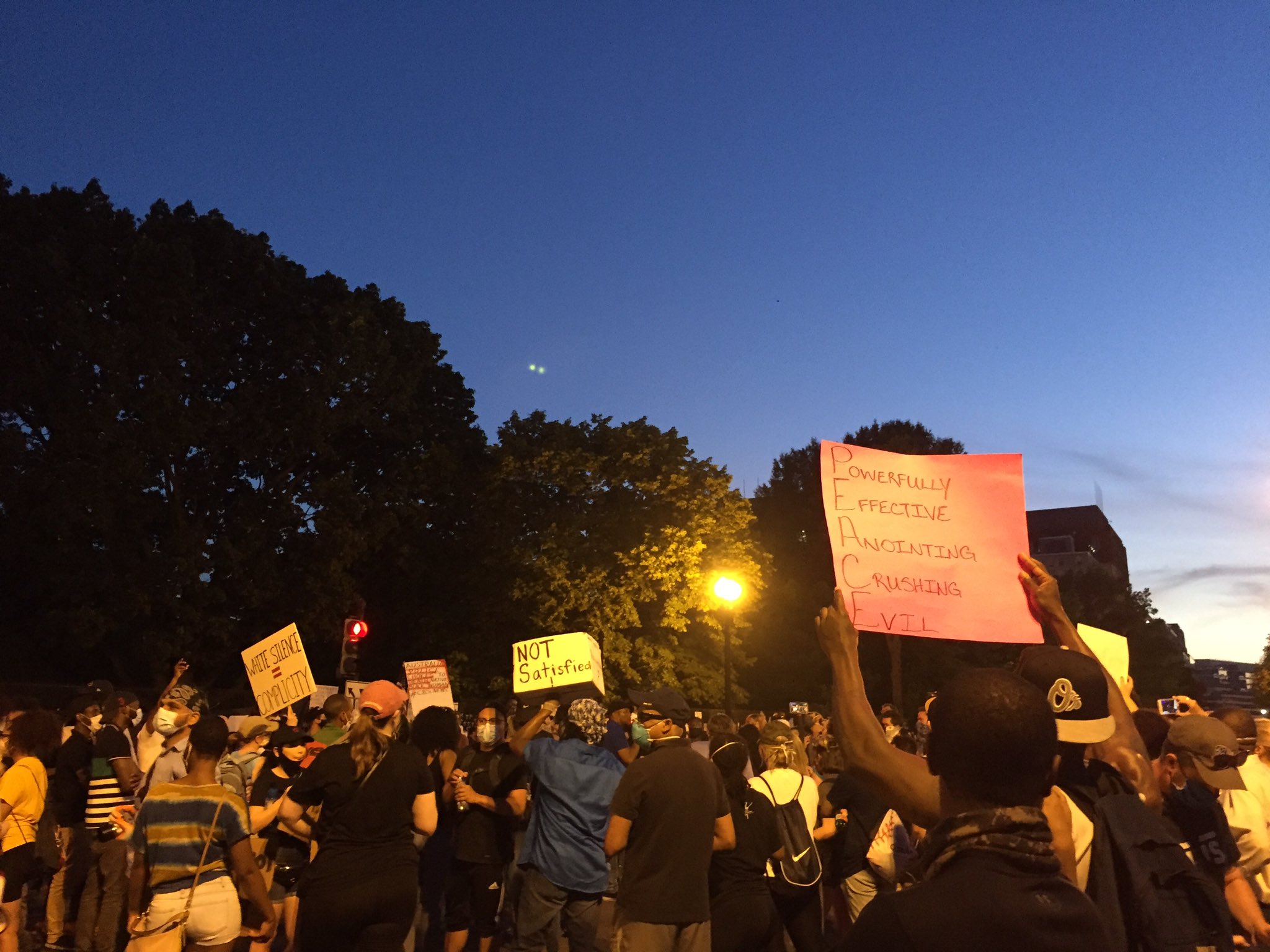

A day after D.C.’s largest protest yet against police brutality, demonstrators gathered once again in groups across the city on Sunday. But where Saturday’s massive crowds felt marked by celebration, these demonstrators have seemed focused on planning strategies for the future of the movement.

Though Sunday’s crowds did not appear to reach the estimated tens of thousands of protesters who came out on Saturday, at least half a dozen groups launched demonstrations around D.C. Many started or ended around the flash point of more than a week of protests: the newly renamed Black Lives Matter Plaza at the corner of 16th Street. While on Saturday the plaza and its two-block Black Lives Matter mural hosted an impromptu dance party—prompting some criticism from activists—the next day it was the site of a die-in shortly before 5 p.m., as well as gatherings that remained beyond 10 p.m.

D.C. has hosted 10 consecutive days of protests following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, some of which early last week were marked by striking images of a city suddenly flooded with law enforcement: Masked troops guarding the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, widening fencing around the White House, and a medical helicopter flying low over a crowd of protesters in Chinatown.

But for days, demonstrations have been peaceful. One arrest was made on Saturday, for destruction of property—the first protest-related arrest in the District since Wednesday. The National Guard and about 900 active-duty troops have been ordered to leave the region, having arrived early last week. The D.C. National Guard and the Metropolitan Police Department remain active in the city.

As the city entered double-digit days of demonstrations, protesters on Sunday seemed motivated by one question: What comes next?

Marcia Santos, a Gaithersburg resident who was among protesters at Black Lives Matter plaza in the morning, emphasized the importance of voting. She said times are uncertain “and we’ve got a voice. The thing is we’ve got to make sure that it’s heard, and it’s only heard by us voting.”

Protesters marched down 16th Street also made voting a part of their message, chanting “vote him out,” referring to President Donald Trump.

Santos said that in order to make an impact, citizens have to turn out not only for the November election, but local elections, too. “People want change,” she said. “That only happens when you vote.”

Another Maryland resident, Sheldon Barber, also emphasized the need for police reform. He told DCist he was also at Saturday’s massive protest, carrying a sign that read, “We need to make it harder to become a police officer, and easier to be black.”

“The training needs to be improved, and the discipline needs to be improved,” Barber said. “When officers do violate the code that they’re supposed to uphold, the punishments need to be stricter.”

The D.C. Council is set to vote Tuesday on a new bill from Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen, which calls for outlawing chokeholds, among other police reform measures. Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau introduced her own bill last week to ban the Metropolitan Police Department from using tear gas on protesters.

Salim Adofo, commissioner for ANC 8C07, said that while having a cause to rally against, like police violence, is effective, demonstrators will eventually have to look at issues facing black people in broader terms. He was organizer and emcee of the Next Steps rally, organized by the National Black United Front, that started in the evening at the African-American Civil War Memorial on U Street.

“If we’re talking about black lives mattering to people, it’s not limited to police brutality, it’s not limited to just education,” he said. “It encompasses those things, but there’s just so much more there.”

The goal of the Next Steps rally, Adofo said, was to give protesters a variety of local causes and organizations to throw their support behind. Speakers talked about affordable housing, the racial wealth gap in D.C., and early childhood issues affecting black children, in addition to police reform. Candidates for the Board of Education, the open at-large seat on the D.C. Council, and a handful of ANC races also joined in to talk about converting the energy of protests into power at the ballot box.

Organizers also made time for moments of solemnity, especially during a soulful performance of Donny Hathaway’s “We Need You Right Now.” About 100 protesters were gathered, listening in silence.

“We need you right now, Lord.”

Crowd of about 100 gathered by the African-American Civil War Memorial on U Street is mesmerized. So am I. pic.twitter.com/GU0tv83BRF

— Margaret Barthel (@margaretbarthel) June 7, 2020

At gatherings around town, not everyone agreed about the likelihood of drastic reform.

In an emotional speech before a crowd at Black Lives Matter Plaza around 1 p.m., Keyone Carr called attention to black Americans who have died during confrontations with the police whose names remain largely unknown.

Her cousin, Asshams Manley, was shot and killed by police in Prince George’s County in 2015. Police said Manley had struggled with the officer over his gun. “There was an assumption of guilt,” Carr told the crowd.

Shortly after speaking, Carr, who is 35 and grew up in Anacostia, told DCist she believes that substantial change to established American systems will be a challenge.

“It’s taken so long to build these institutions,” she said. “How long is it gonna take to undo all of this work? And first, we have to get people to even admit that this work needs to be done. So sometimes it seems insurmountable. But I’m out here because I have hope. I’m out here hoping that maybe we can have some of that change.”

Across town in wards 7 and 8, a pair of faith-based marches merged, with hundreds of protesters stopping at the U.S. Capitol for a moment of prayer. Pastor Thabiti Anyabwile of the Anacostia River Church, one of the protest’s leaders, told DCist/WAMU that he hadn’t seen many of his neighbors join previous gatherings in downtown D.C. It’s not easy for everyone to take a day off of work to participate, he said, “and so people are [contending] with a lot of things that are in their own right important that might make it more or less possible for them to participate.”

On Sunday, as the march passed into Capitol Hill, bystanders cheered from the sidewalks and offered water to participants. “That moved me to tears to see little children with their little signs saying, ‘we support you, we care,’” said Christopher Butters, a Fairfax resident who joined the protest.

Utah Senator Mitt Romney also joined their march, traveling from the U.S. Capitol to Lafayette Square, and tweeted “Black Lives Matter.” According to the Washington Post, he’s the first Republican senator to join D.C.’s protests.

While the new Black Lives Matter Plaza outside Lafayette Square has been a gathering place for protesters since it was dedicated on Friday, some have criticized it as being emblematic of action without meaningful change. The D.C. Black Lives Matter chapter tweeted that the two-block “Black Lives Matter” mural is “performative,” and said it distracted from D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s alleged failure to make significant changes to the District’s justice system.

On Saturday, local activists painted over the stars in the D.C. flag to create an equal sign, and added “Defund the police,” so the word read as one pronouncement. City officials later restored the stars to the flag, but have so far left the added words untouched.

Throughout Sunday’s demonstrations, protesters shared misgivings about the city’s work.

Johnnie Williams, who was handing out snacks and water near the plaza, raised concerns about Bowser’s proposed budget increase for the MPD. At the Next Steps rally, three of the candidates for the District’s At-Large Council seat—Marcus Goodwin, Ed Lazere and Christina Henderson—also brought up Bowser’s budget.

“While we appreciate the small gestures of the Black Lives Matter Plaza, painting the streets, that doesn’t mean anything for substantive change and accountability,” he told DCist. “And that is something that people on the streets are also asking for as well. So while we appreciate the visual gestures, we also need to see that in policy.”

On Vermont Avenue NW, Tanzi West Barbour, a Ward 5 resident, said she disagrees with calls to defund the police. “I think anyone who takes the weight on their shoulders to go out and protect us every single day and in the line of fire, I don’t think that they should be defunded,” she said.

Barbour said that growing up in Anacostia, she felt that police kept the neighborhood safe, and believes that to this day. “I can’t speak for every police officer at MPD, but the ones that we know are doing an excellent job,” she said.

Across the District, activists from various backgrounds led protests, from the Christian march from wards 7 and 8, to the rally hosted by LGBTQ activists in Columbia Heights.

One attendee at the latter demonstration named Rasa, who declined to share their last name, said coming together that way is key, adding that any movement to fight oppression must highlight other vulnerable groups, like trans and non-binary people.

“I think that’s a part of this that can’t be missed,” said Rasa, who recently graduated with a degree in psychology from American University. “Because if your activism isn’t intersectional, it’s useless.”

As the city wraps up 10 days of these protests, some emphasized they would continue to come out.

“I don’t know how much I’ll be able to get up, having to work this coming week,” said Barber, protesting at Black Lives Matter Plaza. “But I will be here as often as I can.”

By 10 p.m. the crowd around the White House had significantly thinned, but a couple hundred people remained. Most people were milling about and talking, or admiring the collection of artwork and signs along the fence in front of Lafayette Square.

Lawrence, who declined to share his last name, offered hand sanitizer and water to people as they walked north up 16th Street and left for the evening. He said he had been at the protest since around 10:30 on Sunday morning—and he had been attending the protests in front of the White House for seven days straight. What began with a case of water, two bags of ice, and a cooler had turned into a table full of free supplies and snacks, made possible in part by donations from other protesters.

To Lawrence, the orderliness of the protests was an argument that large police forces are not necessary to keep people safe.

“No one’s gotten into a fight, no one’s gotten robbed, nothing has happened,” Lawrence said. “We’re all standing together, we’re all giving away stuff, we’re all helping each other. I’ve got band-aids, ACE bandages. If someone falls and sprains their ankle, I’m here to help.”

Lawrence, who is black, said he was tired, but he planned to return again the next day.

“I look at it this way: I should be able to do this and support as long as I’m the color that I am,” he said.

This post has been updated throughout.

Lori McCue

Lori McCue Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz Margaret Barthel

Margaret Barthel Jenny Gathright

Jenny Gathright Daniella Cheslow

Daniella Cheslow