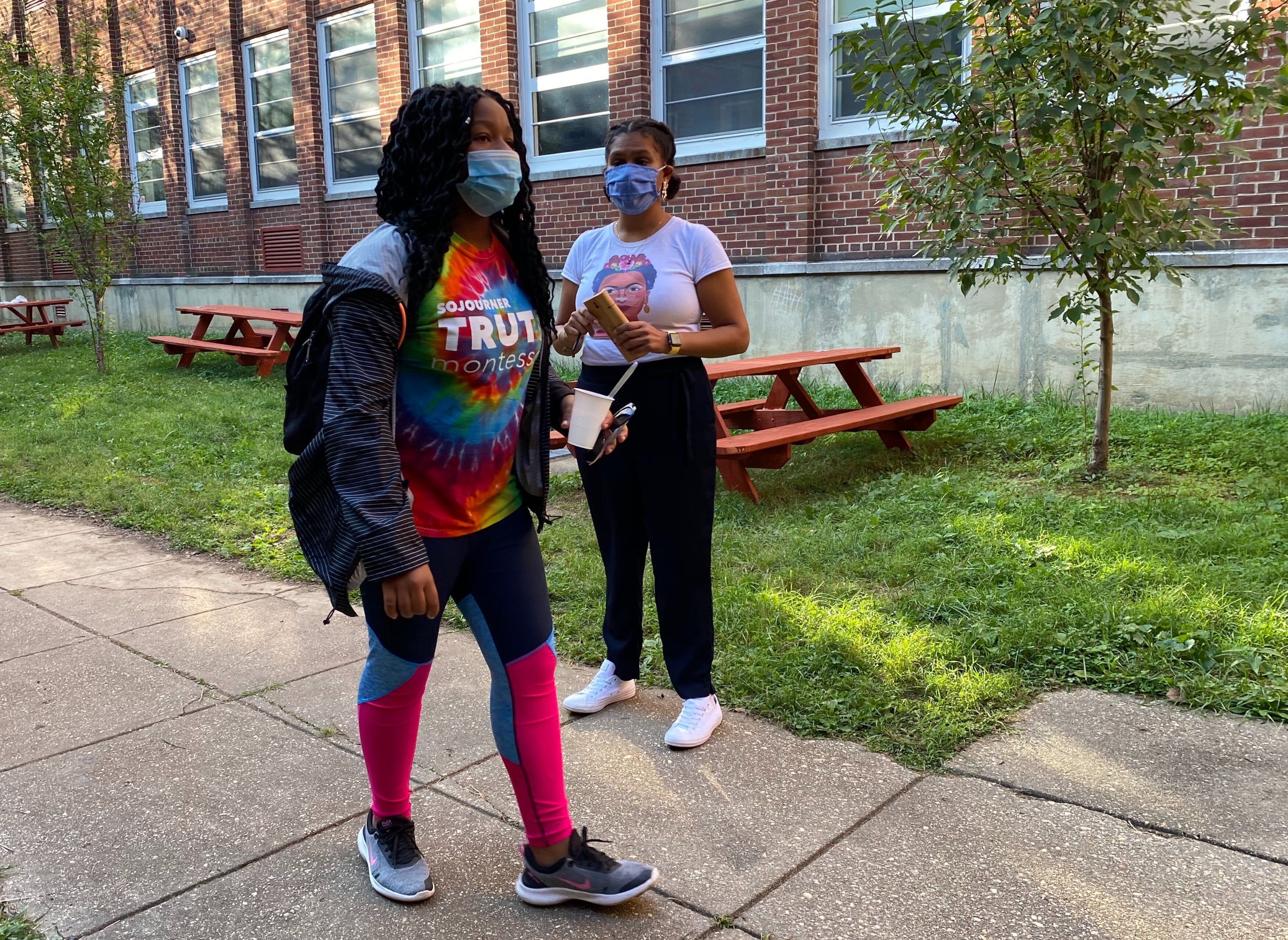

When the Sojourner Truth Public Charter School asked families if they wanted in-person learning this school year, China White and her mother, Izu Ahaghotu, easily answered: yes.

“I know my child and she needs the in-person learning for social, physical, mental wellbeing,” said Ahaghotu, a single, working mom, as she dropped her daughter off one recent morning.

Eleven year-old China said school got complicated when classes moved online in the spring. Live video streams of her virtual classes were often choppy, forcing her to try and piece together bits of information from class lessons.

“I couldn’t really focus,” the sixth-grader said, adding that she feels Truth is doing a good job of enforcing mask wearing and social distancing.

Most students in the Washington region have not set foot in a physical classroom since classes largely shifted online in March. But the school in Northeast is one of about a dozen D.C. charter schools that are offering some form of in-person instruction to small groups of students. City education officials are closely watching schools like Truth as D.C. Public Schools eyes a possible return to in-person education.

Mayor Muriel Bowser said she wants the school system, which educated 51,000 students last academic year, to provide a mix of in-person and online learning when the second grading quarter starts Nov. 9. Large school systems in Northern Virginia, including those in Fairfax and Loudoun counties, are expected to bring small groups of students back for in-person instruction this month.

Unions representing teachers and principals in D.C. have fought plans for any broad return to campuses during the pandemic, arguing the city has not provided enough details about how it will keep students and educators safe.

About 90 students are enrolled at Truth, a Montessori middle and high school that opened this year. The school surveyed families about their learning needs and were able to more easily accomodate families’ requests for in-person or virtual learning because of the school’s small size, said Justin Lessek, the school’s founding executive director.

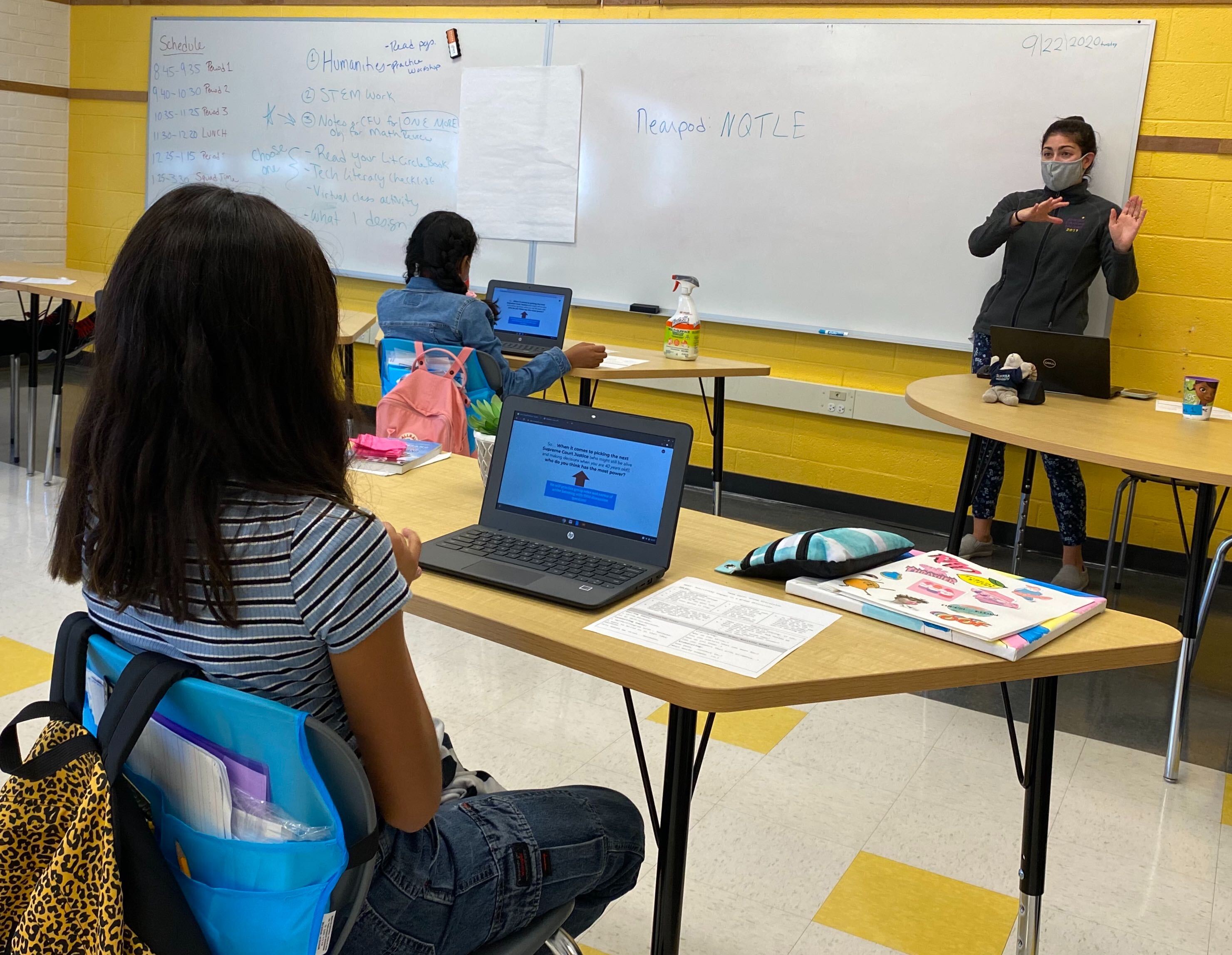

Twenty students in sixth and seventh grade are currently taking a full day of classes on campus, five days a week. Some are the children of essential workers, others are enrolled in special education and need extra support from an instructional aide during the school day.

The students were divided into two cohorts of 10 that are kept in separate classrooms throughout the day. Class transitions are staggered so the children do not crowd the hallways. Face masks are mandatory and gallon-sized bottles of hand sanitizer are placed across the school.

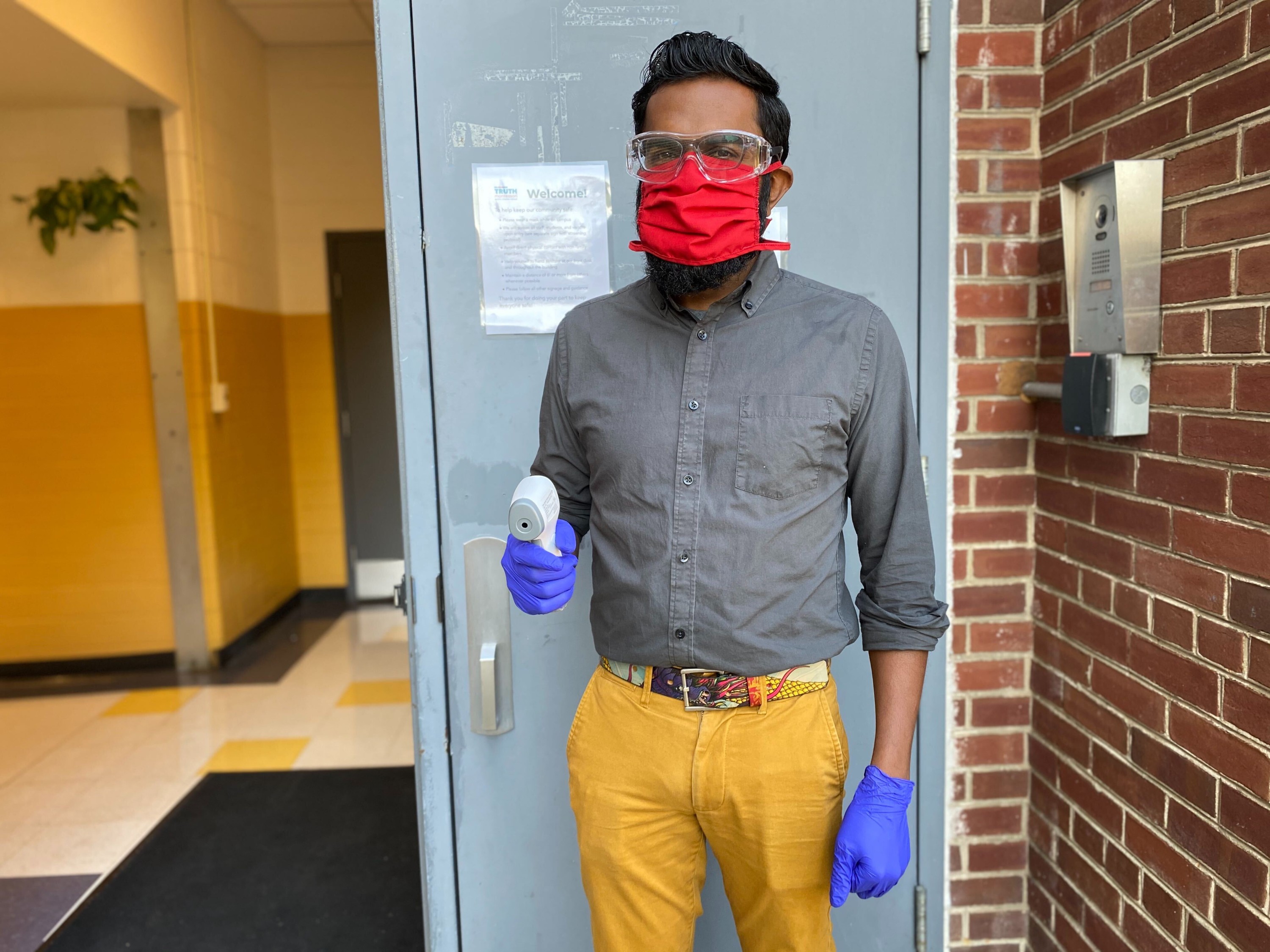

A school worker stands outside each morning, taking students’ temperatures using a forehead thermometer. Each person is quizzed on their health before they enter the school and are isolated and sent home if they show any signs of illness, including fever, cough, congestion, sore throat, diarrhea, nausea or fatigue.

One student was isolated at the school this academic year for a headache. The student returned to school after they tested negative for the coronavirus, Lessek said.

At Meridian Public Charter School in Columbia Heights, 19 students are receiving in-person instruction in two “learning hubs” four days a week. Other students visit the school for shorter periods of time during the day for counseling, occupational therapy sessions and other services, said Head of School Matthew McCrea.

Air purifiers were placed throughout the building and the school purchased a washer and dryer, which they plan to use to launder cloth face masks for students daily.

McCrea said a consultant who works with Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) visited Meridian during its first week of in-person learning and made suggestions about protocols, including swapping signs reminding students to social distance with posters that were created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Schools in the District submitted plans to OSSE describing how they will provide education to students during the pandemic.

“The amount of public health guidance that I’ve read in the last six months is shocking,” McCrea said. “To a certain extent, you can never prepare for something like this. To another extent, being flexible and responsive is something educators do everyday.”

At Truth, students are encouraged to study and explore outside as much as possible, said Principal Denise Edwards. Breakfast and lunch are held outdoors, where students’ assigned seats are spread across several large, red picnic tables. WiFi was routed to the school’s courtyard so teachers could hold class lessons outside.

“Socialization is also a huge part of adolescent development,” Edwards said. “We did not want to completely isolate students from each other.”

Students’ face masks occasionally slip down the bridge of their nose or they forget to keep a six feet distance from classmates. Teacher Johari Malik said the students are responsive to reminders.

“They’ll slip up if they get excited about something but they take the reminders really well,” she said. “They know that it’s not this arbitrary ‘stay away from each other, don’t teach anyone’ thing. They get it.”

Malik, a STEM teacher, said she was torn about the possibility of teaching in-person but ultimately felt Truth is taking the right precautions. She said she would not have felt comfortable with face to face instruction if the school allowed all students to return.

Teachers who are teaching in-person at Truth are doing so voluntarily. Malik’s day is split between teaching in-person and virtually. She leads the online sessions from a large storage closet inside her classroom — the only place in the school building where she can remove her face mask because the space is not shared with others.

Inside the classroom, desks are spaced apart and students have their own set of supplies. During a lesson about converting centimeters into millimeters, Malik directed the children to measure four of their personal belongings.

One girl declared she needed help measuring a strand of hair. Another girl rose from her desk, shuffled a few steps and stopped. She peered at the measuring tape, relaying the measurement to her classmate from a distance.

Debbie Truong

Debbie Truong