For Sakeenah Shabazz, 27, voting this year couldn’t have been easier. The Ward 7 resident received her ballot in the mail, made her selections, dropped the ballot back in the mail, and later checked online to see that it and been received and accepted. It had.

“It was really smooth,” she says of the voting experience, which expands Tuesday with the start of in-person early voting at 32 vote centers across the city.

That’s exactly what D.C. election officials want to hear, especially after the problematic June primary and their subsequent decision to take a gamble and do something they had never done before: send every registered voter a ballot in the mail, no request needed. In so doing, D.C. joined a relatively small number of states — nine in total — that planned to directly send voters a ballot for the November election. (Many states have expanded their use of absentee ballots, which voters have to request.)

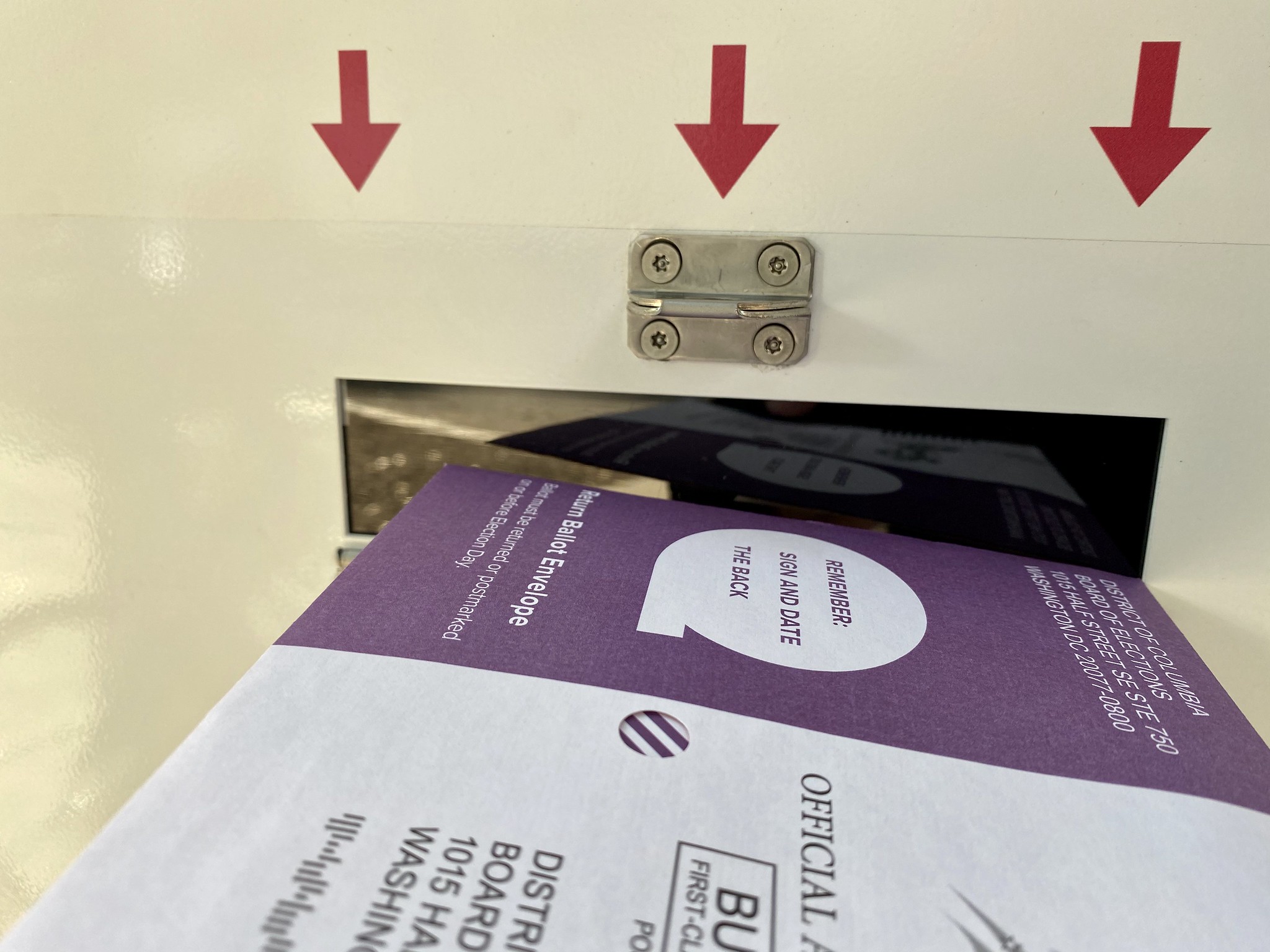

“Nothing’s perfect, right? But I think things have been going pretty well,” says Michael Bennett, chair of the D.C. Board of Elections. “The vast majority of the feedback I’ve got from from folks is that they’ve been really pleased to get the ballot and put it in a drop box.”

As of Monday, 146,192 people have voted by mail so far, representing 46% of the total turnout during the 2016 election. (That year, by comparison, D.C. only processed 20,781 absentee ballots.) Voters tell WAMU/DCist that getting and returning their ballots by mail or at ballot drop boxes was “simple and great,” a “wonderful teachable moment” for kids, and “one of the better [D.C. government] experiences I’ve had.”

But just like with any big change, there have been growing pains in D.C.’s sudden move to mail voting. And some of those pains have been sharper because of the political sensitivities involved: With President Trump repeating baseless claims of voter fraud and Republicans fighting in a number of states to limit the use of mail ballots, many voters are even more intent in making sure their vote actually counts.

That’s where Jeff Rosa, 48, found himself. The Ward 2 resident returned his ballot earlier this month, but for more than two weeks it had been listed as having been received, but not accepted.

Every incoming ballot envelope is scanned by the board, largely to check that the voter’s signature matches the signature on file. If it doesn’t, the ballot is flagged for a secondary review. If there’s still a concern after that, the board is supposed to contact the voter and give them a chance to “cure” their ballot, or basically verify it is actually theirs.

Rosa says he never got any clarity on how long he should have waited for his ballot to move from having been received to being accepted, and how long a possible review would take. And it made him nervous that his vote might not ultimately count, even if the presidential race isn’t expected to be competitive in D.C.

On Tuesday, the ballot-tracking system finally updated to say Rosa’s ballot is “under review,” and shortly thereafter it was accepted. He says he’s relieved, and says it was still better than waiting in line for hours to vote in person.

“This won’t dissuade me from voting by mail, but it reinforces the importance of staying vigilant and ensuring that your vote is accepted and not just received,” he says.

Other voters have had similar experiences of waiting undetermined periods of time for their ballots to be accepted. Jeremiah Lowery, the head of local advocacy group D.C. for Democracy, had his ballot initially rejected; The situation only got resolved after he reached out to Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen, who oversees the elections board.

Election officials are pleading for patience from voters, saying that they are dutifully processing every ballot. The status of a ballot may not change for a few days simply because of the volume of ballots that are being received and reviewed. They also say that ballots are not necessarily processed in a first-come, first-served order.

“It takes two or three or four days sometimes for the [ballot tracking system] to report that your ballot has been received,” Bennett says. “It is not because it’s under review. It’s just because we don’t upload data into the ballot track system but once every two days.”

The elections board has also been trying to reassure voters over social media that it is making its way through the ballots, and that an overwhelming majority won’t be caught up by review. In D.C.’s June primary, roughly 1% of absentee ballots were rejected because of issues with the signature; a similar percentage of absentee ballots are being caught in Virginia for curing.

“If there is an issue with the ballot — a very, very small chance there is — we will reach out to resolve. You can be 99.44% sure your ballot is fine and will be fully processed and tabulated very soon,” the board tweeted on Monday in response to a voter.

Nick Jacobs, a spokesman for the board, says that if any voter’s ballot remains in limbo as Election Day approaches, they can go to a polling place a cast a provisional ballot. “If the ballot under review is accepted the, of course, the provisional would not be counted,” he says.

The elections board has until 10 days after Nov. 3 to cure and count all mail ballots, provided they were postmarked or dropped off at a ballot box by Election Day.

Kathy Chiron, the president of the League of Women Voters of D.C., says she’s gotten “mixed reports” about D.C.’s mail voting system. While some people have been able to vote with ease, others have had concerns around whether their ballots had been received and counted. Chiron says part of the challenge is educating voters, but also having an elections board that is more responsive.

“It takes several attempts to get through,” says Chiron of voters’ attempts to call the board when issues arise.

And that’s what Katie Lootens, a Ward 1 voter, says her experience was: When she had a problem getting registered, it took a number of requests for help to get it addressed. She’s happy her situation got fixed, but worries that people who don’t have time or resources may fall through the cracks.

“All of the individuals I’ve ever interacted with at [the elections board] have been helpful and kind! But I think their electronic records system is super slow, and I’m worried that if someone who was less aware or had less time but was in my same situation wouldn’t be able to vote because it’s too complicated,” she says.

Gordon-Andrew Fletcher, an ANC commissioner and president of the Ward 5 Democrats, agrees that better communication and education would be helpful; he says the voter guide every D.C. household got, for example, could have been more informative. But he says despite some of the hiccups, the mail voting system has worked well in D.C.

“It’s still a work in progress, but I still think the D.C. Board of Elections got it right by doing this versus just having traditional voting,” he says. “But there are still some things that we could do better for for the next go around.”

Advocates of mail voting say those hiccups and challenges are to be expected, especially considering that D.C. quickly implemented a mail voting system that some other states have taken years to perfect. But now that mail voting has been used, they expect that it will remain in place for future election cycles.

“There’s a lot of moving pieces to an election, and I think we’ve sort of been lulled into this false sense of, ‘Oh well, in person, it’s just so much easier, we should just keep doing this,'” says Audrey Kline, the national policy director for the National Vote at Home Institute. “Once people start voting by mail, it’s very rare for them to go back or stop.”

Last year, a bill was introduced in the D.C. Council to move the city towards a full vote-by-mail system. But Bennett says that current circumstances — not just a legislative mandate — could push the elections board to keep its mail voting system for future elections.

“I think that that life has changed because of the pandemic in a lot of ways,” Bennett says. “This just may be one of those changes that we’ve been pushed into that we’ll probably stick with for a while.”

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle