Those who knew the late Senate President Mike Miller say that while he was a giant presence during his four decades of public service in Annapolis, he was also a complicated character whose slow-going political approach got things done — but often too slowly for some.

The 78-year-old died last week after a long battle with prostate cancer.

Ensconced inside a casket draped with the Maryland flag, Miller lay in state under the statehouse dome on Friday. It was a building he knew well: He was elected to the House of Delegates in 1970 and then to the Senate four years later. Miller is the longest-serving state senate president in the history of the nation, having ascended to the position in 1987.

Miller’s family and friends will hold a private funeral and interment for him on Saturday in Clinton.

In a Senate ceremony on Friday, Miller’s portrait loomed above the chamber, a black cloth draped over it.

“He’s staring at me right now with that smile of his with that twinkle in his blue eyes,” said Republican Gov. Larry Hogan while looking over at the portrait. “I’ve seen that look many times over the years like he’s getting ready to lambaste me if I go off course or say something a little too partisan.”

Hogan choked up while talking about his six-decade-long friendship with Miller. Hogan first met the late-senator in 1962 while Miller was helping Hogan’s father, Larry Hogan, Sr., campaign for governor. Then 19-year-old Miller would sometimes be asked to babysit the five-year-old Hogan, Jr. Miller later became a Democrat. “I don’t know what went wrong,” Hogan said.

But Hogan added that even though they were on opposite teams, their friendship survived. “When Mike was your opponent you knew you were in for a battle, but when Mike was on your side, he was really on your side,” Hogan said.

That friendship and mutual respect only grew deeper when Hogan was diagnosed with cancer, and later with Miller’s own diagnosis.

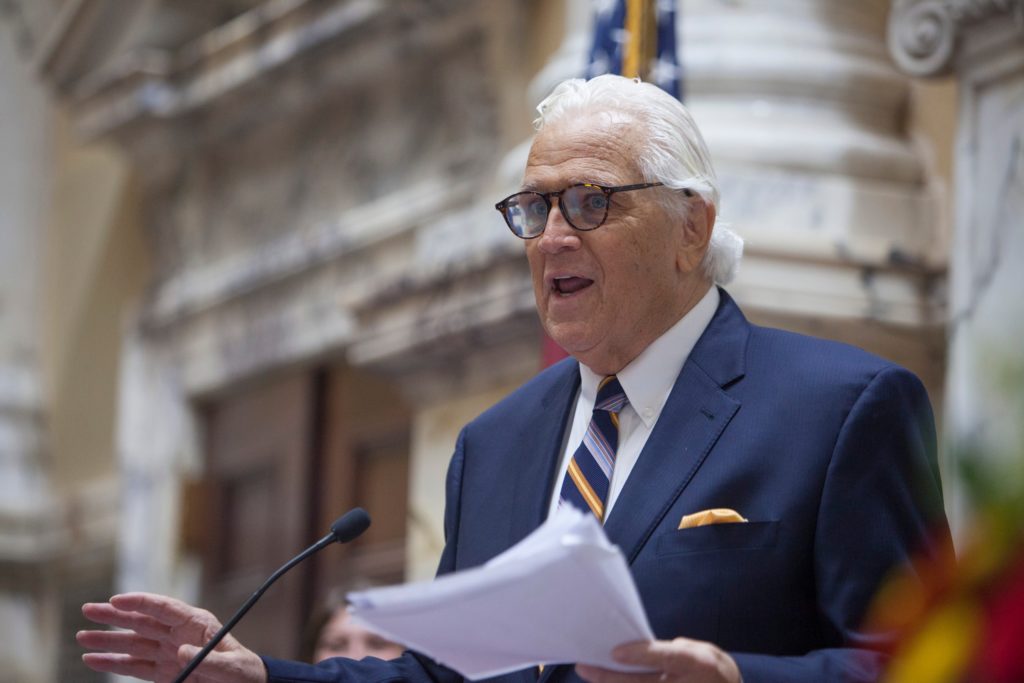

Standing at the lectern with a photo of Miller at his side, Senate President Bill Ferguson (D-Baltimore City) began by saying the late-senator’s full name: Thomas Vincent “Mike” Miller, Jr. “What a name,” said Ferguson.

“Mike Miller has no twin. There is no one like him,” Ferguson continued, referencing Miller’s given name, the Semitic word for twin. “I think what made Mike Mike was the duality in the way he approached this work. The country boy from Clinton, versus the kingmaker in Annapolis.”

Ferguson went on to explain that in planning for this year’s legislative session he informed Miller of the lengths to which he went to protect lawmakers from COVID-19. When Ferguson texted a photo of the Senate floor to Miller, the senator was taken aback by the plexiglass-encased desks physically distanced from each other. “Bill,” he wrote, “you made the Senate floor look like a [expletive] kindergarten classroom.”

“That was Mike, that’s who he was, he’d tell you how it is,” Ferguson said.

Miller served in his Senate seat until resigning last month. In a resignation letter to Ferguson, Miller wrote that his long-standing health issues made him “too weak to meet the demands of another legislative session.”

In October 2019, Miller’s cancer diagnosis prompted him to step down as the Senate’s president after more than three decades of service. But he remained a prominent figure in the Senate, serving as the representative for Calvert and Prince George’s counties during the 2020 legislative session.

A complicated history

Miller was Catholic, born in Clinton and raised in a predominantly conservative district of southern Maryland.

“He had to keep those folks happy,” said Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh, who served with Miller in the Senate for 20 years, to WAMU/DCist in 2019. “And at the same time he had to keep the Senate Democratic Caucus happy.”

Frosh said that he disagreed with Miller on many issues, but Miller was “good at getting the sense of the Senate and moving in the direction the chamber wanted to go in.”

That was most visible through Miller’s political tact, especially in moving forward slowly on issues like casino gambling, taxes, same-sex marriage, and abortion rights. But some say it was that very political tact that impeded progress for his Black constituents in Prince George’s County.

A group of University of Maryland students from Black Terps Matter and Greenbelt Mayor Colin Byrd started a petition to remove his name from the campus’s administrative building. It was added last summer when the protests over the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis shook the nation.

“We found out that in the past, he’s been very racist and used his platform to counter progressive police reform and gay marriage,” Saba Tshibaka, one of the group’s organizers, wrote in the petition.

Byrd told WAMU/DCist that while he’s sympathetic and empathetic toward Miller’s family and friends, he said Miller’s legacy is at odds with the values and mission of the university.

“I do think that you can say some good things about Senator Miller… but the thing is, that doesn’t necessarily warrant having your name and class and prominence on two of the most prominent state buildings in all of Maryland,” Byrd said.

Miller’s name is also enshrined on the Senate Office Building in Annapolis. Byrd said Miller and U.S. Representative Steny Hoyer (D-Maryland) led redistricting efforts in 2011 “that diluted the power of Black voters in his district.”

Byrd added that in 2017, lawmakers wanted to censure Miller for criticizing the State House Trust for removing the memorial to the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney from the state house lawn. Taney was a Maryland native and author of the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision that found that Black Americans could not be citizens.

In a letter to Hogan that year, Miller, a history buff, admitted that Taney’s language in the Scott decision was “derogatory and inflammatory.” But he also added that Taney “served with distinction” in a number of public offices.

Miller noted that Taney, a slave-owning resident of Calvert County, freed his slaves and remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. He added that Taney’s “complex history” was often lost amid discussion.

David Lublin, a professor of government at American University, says that in hindsight Miller’s views can be criticized, but that the late senator still fought to move Democratic causes in the state forward.

“What a lot of people don’t seem to realize is that context changed and the way people viewed things changed, and that some of the actions they’re taking right now may not viewed so well in 20 years either,” said Lublin. “We have to recognize his diverse views.”

Lublin adds that Miller was determined to get Democratic lawmakers of color from marginalized districts into their senate seats. He raised former Baltimore City Sen. Joan Carter Conway to the position of chair of a standing committee — the first Black woman to reach such a position in the Maryland General Assembly.

Vicki Gruber, the senator’s longest-serving chief of staff, said Miller was more progressive than he was given credit for.

“People see his positions [on issues] from over 30 years ago, but they probably don’t know why Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman [statues] are in the statehouse,” she said. “You think you know the whole story, but you don’t.”

This story was corrected to reflect that Miller’s casket was draped with the Maryland flag and not the American flag.

Dominique Maria Bonessi

Dominique Maria Bonessi