On a sunny and cool late winter day, Karl Van Neste was volunteering at a trash cleanup in Gaithersburg, Maryland. At one end of a small lake, floating amidst the debris, he found a number of dead fish, their glossy eyes staring at the blue sky.

“I said, ‘Let me let me just check to see what the salt level is here,'” Van Neste recalls. He went back to his car to fetch the chloride testing strips he uses to check for salt.

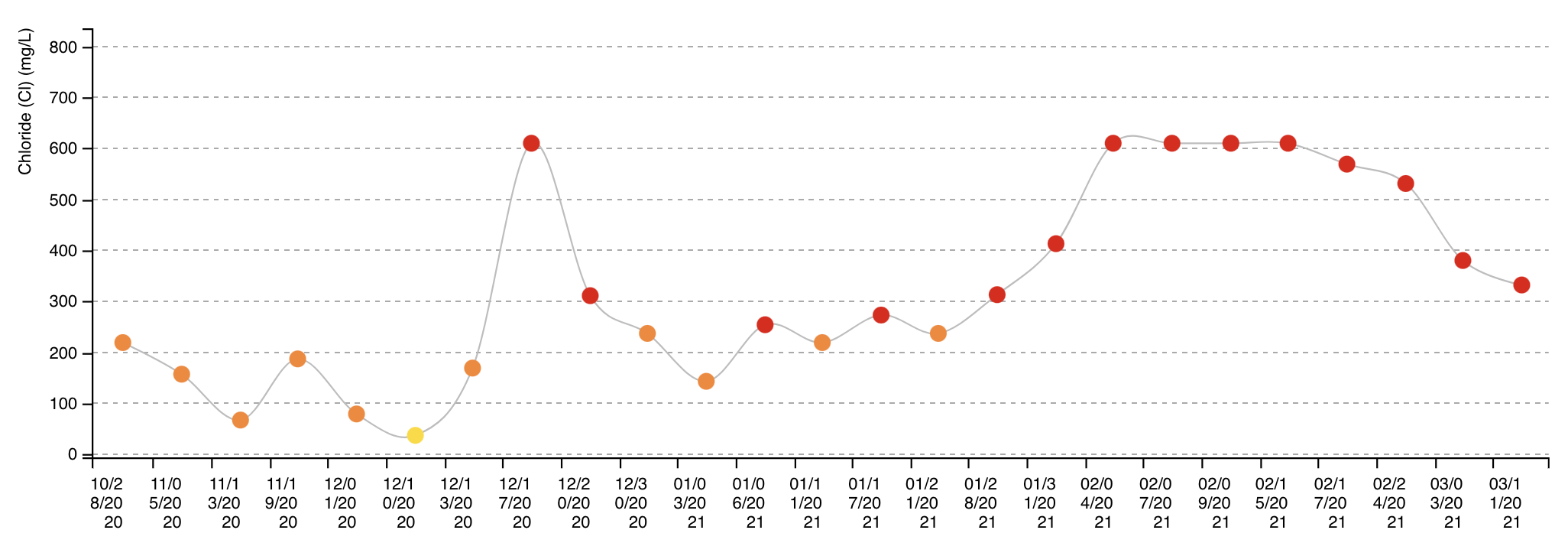

The salt level was off the charts — above 600 parts per million, the maximum level the testing strips can detect.

Road salt helps keep streets, sidewalks and parking lots clear during snow and ice storms. It’s cheap and doesn’t require a lot of manual labor. But it’s also toxic to the freshwater creatures living in local streams, where the salty runoff from roads ends up after a snowfall. Road salt is also bad for humans: after it washes into the watershed, salt salt from roadways ends up in our drinking water. Along the way, it corrodes infrastructure, from bridges to water pipes.

Van Neste is director of the Muddy Branch Alliance, a local environmental group that has been conducting regular water testing for salt since late 2019.

“Along with every snow event or winter event, we always see these huge, huge spikes in the chloride level and they take time for that to drop back off,” says Van Neste.

“It’s not clear that salt is what killed the fish,” Van Neste admits. But circumstantially, he says, salt appears to be the culprit.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, chloride can be toxic to aquatic life if it is present for long periods at levels above 230 parts per million. A short exposure to chloride at 860 parts per million can also be lethal.

This winter has not been excessively snowy, but there were an unusual number of back-to-back snow events. Since Jan. 31, there have been nine snowstorms with measurable accumulation — the most since 1899. Because D.C. is frequently right on the line between snow and rain, governments and property owners often cover surfaces with salt, even when no snow materializes.

Other toxins could be at play in the fish kill, however. Emily Bialowas runs the Winter Salt Watch program with the Isaak Walton League, a national conservation organization based in Gaithersburg. She says given the recent warm weather, residents in the neighboring housing development were likely out doing yard work, possibly applying fertilizer or pesticides. Such chemicals could also have lead to the demise of the fish.

“I can’t definitively say, ‘Yes, that killed those fish,'” says Bialowas.

Salt levels in streams show obvious spikes after snowstorms. But salt also lingers in the environment. “It’s not just a one time thing,” says Bialowas, noting that even after snow melts, salt remains on the pavement and next to roadways.

“It can rain a few times, and each of those times the chloride levels are going to spike in the stream,” Bialowas says. “We’ve seen some really high levels, especially this year.”

Last winter, the Winter Salt Watch program recruited volunteers to test water for chloride in 17 states and 39 watersheds. One-quarter of all samples showed hazardous levels of salt, while an additional 30 percent had levels above what is naturally found in fresh water.

Bialowas says despite the name and focus of her program, salt is not only a winter problem. Elevated chloride levels can persist even into the warmer months, and the hot weather can further stress creatures in the water. “The high temperature and the chloride can become even more lethal to aquatic life,” says Bialowas.

As for salt in drinking water, Van Neste says he’s done some testing at home. In the fall, before any snowfall, he says chloride levels were low — about 35 to 40 ppm.

“Then I did it in February after one of our snow events, and it was over 130 ppm,” Van Neste says. “If your water tastes salty, well, that’s because it is.”

Water tastes salty to humans when chloride levels are above 180 ppm, according to the EPA, but some people can taste it at levels as low as 30 ppm. The agency recommends keeping sodium levels below 60 ppm in drinking water.

In recent years, many local governments have been attempting to reduce salt use. D.C. uses salt brine mixed with beet juice, which sticks to roadways better than rock salt, meaning less is needed. Maryland has a salt management plan in place, aimed at cutting salt use. And Virginia recently unveiled salt management strategy to reduce salt pollution in Northern Virginia.

But Van Neste says it is frequently private property owners who are most egregious in over salting surfaces, in an attempt to keep parking lots and walkways as clear as possible. “They’re afraid of being sued,” he says. “And the other issues is they want to look like they’re open for business.”

He says more awareness of the problem can help, as can changing residents’ expectations after a storm.

“We can’t expect every inch of every road to be clean after a snowstorm.”

Jacob Fenston

Jacob Fenston