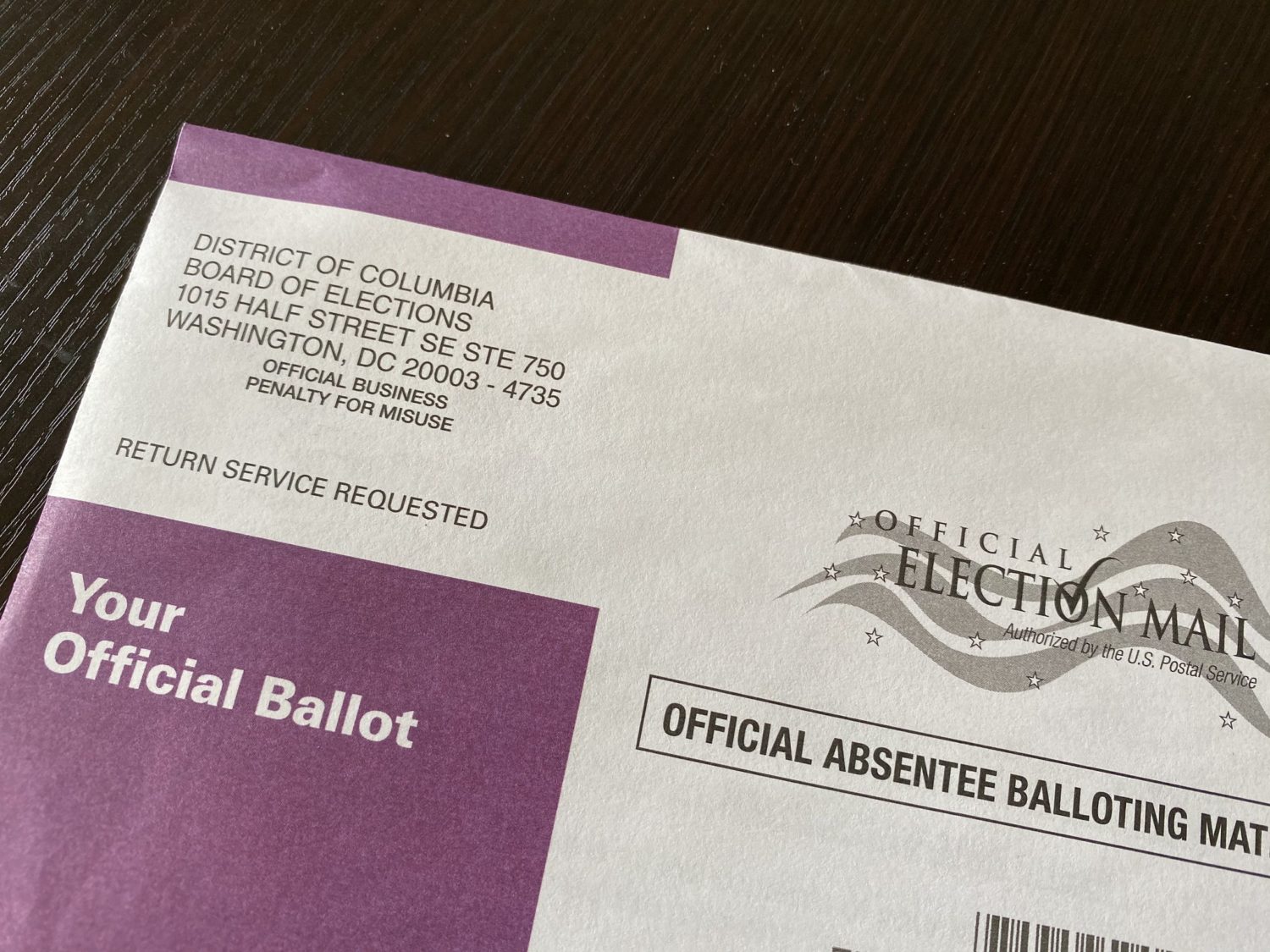

When D.C. sent every registered voter a ballot in the mail ahead of last November’s election, it was pitched as temporary adjustment to the realities of voting during a pandemic.

But election officials are now starting to consider whether mail ballots, ballot drop boxes, super vote centers, and other initiatives they tried in November should become permanent. And the conversation is happening just as many states — largely those led by Republicans — are going in the opposite direction, debating bills that critics say would limit access to the ballot box.

The D.C. Board of Elections held the first of two public town hall discussions on Tuesday morning, seeking input from residents and activists on what worked in 2020, what didn’t, and what — if anything — should be carried forward for the 2022 election cycle.

Board officials have already hinted that they are considering keeping the expanded mail ballot system, which proved very popular among voters. More than 200,000 mail ballots were returned by voters for November’s election, easily doubling the number of people who chose to cast ballots in person.

“The DCBOE should maintain some form of a mail ballot program for the majority of D.C. voters,” the board told the D.C. Council in documents submitted as part of the budget oversight process earlier this year.

Speaking on Tuesday, Ward 4 ANC Commissioner Zach Israel encouraged the board to not only keep the 55 ballot drop boxes that were made available for voters, but to dramatically expand their use. “Just having the drop boxes in more neighborhoods would be extremely beneficial,” he said, proposing that each of the city’s 144 voting precincts get their own drop box.

That suggestion prompted a broader discussion on whether D.C. should even bring back its traditional neighborhood-based polling places, or continue the use of citywide vote centers where any voter can cast a ballot. (That could include the use of the super vote centers, which in November included sites at Nationals Park, the Capital One Arena, the Entertainment & Sports Arena, and others.)

“One of the things that would be helpful to think about is should we continue the precinct system? That means you’re assigned to a specific place and on Election Day that’s where you vote,” said Michael Bennett, the board’s chairman.

That could be controversial. Even before the November election, Mayor Muriel Bowser was pushing the board to open all 144 neighborhood-based polling places for November’s election, even though election officials said at the time it would likely be impossible because of staffing and space constraints.

Speaking Tuesday, Dorothy Brizill, a longtime D.C. government watchdog, expressed skepticism over a possible shift away from the traditional precinct-based polling places.

“I am one who still believes in the need for voter precincts,” she said. “I am not an overwhelming fan of vote centers. They are not in residential neighborhoods, there is no parking in many instances. If you’re going to revisit the issue of polling sites, we need a serious hard look at the population surrounding those sites and whether they are accessible.”

Brizill also said the elections board needs to be concerned about some more critical nuts-and-bolts issues, including cleaning up the city’s bloated voter rolls, developing a new voter registration system, investing in additional IT infrastructure and personnel, and coming up with a new app voters can use for information and to register to vote. The elections board quietly killed off its voter app last summer, after complaints that it was unreliable and buggy.

D.C. resident Gabriel Gopen similarly pushed the board to develop a new app, and suggested it work with local developers to test and perfect it. “We have a robust community of election nerds who would play around with something to see if it breaks,” he offered.

The city’s next election cycle comes in 2022, when the mayor’s seat will be up for grabs. That election will also come after the city’s wards are redrawn with new population data from the U.S. Census, potentially altering the shape of a number of wards in significant ways. Given those changes, Brizill suggested the board proceed slowly on making permanent any changes to the way people vote in D.C.

“Having been around elections in D.C. for a long time, I can safely say there is an inherent danger and unexpected consequences can follow from making changes to the election process in direct response to a particular situation like COVID-19,” she said.

The elections board is holding a second virtual town hall on April 20.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle