If you thought you’d have a bit of a break after last year’s intense election-related drama, you’d be wrong.

Along with New Jersey, Virginia is one of the outlier states when it comes to holding statewide elections, opting to run them the year after presidential contests. (It’s known as the off-off year.) That means that voters in Virginia will be picking their governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and the entire 100-seat House of Delegates.

In years past, Virginia’s off-off year election was seen as something of a harbinger of the midterms to come — if the party not controlling the White House could take the Governor’s Mansion in Richmond, it was relatively safe to assume they’d fare well in congressional races, too. Republicans are certainly hoping that’s the case; they haven’t held statewide office in Virginia since 2013 and lost the House, Senate, and White House last year.

Still, the challenges the GOP faces are significant. Not only have Virginia voters become more steadily Democratic, but the commonwealth’s Republican Party has been riven by infighting over everything from messaging to how to select a nominee for the gubernatorial contest. That’s happening this Saturday, May 8; Democrats are holding a statewide primary on June 8.

Here’s everything you need to know about Saturday’s Republican convention.

Which Republicans are running for governor?

There are seven candidates vying to be the Republican nominee for Virginia governor this year:

-

-

- Glenn Youngkin is the former co-CEO of the Carlyle Group.

- Amanda Chase is a state senator from Chesterfield County.

- Kirk Cox is a former Speaker of the House and current delegate from Colonial Heights.

- Peter Doran is the former director of a D.C.-based think tank.

- Sergio de la Peña is a former Defense Department official.

- Pete Snyder is an entrepreneur.

- Octavia Johnson is the former sheriff of Roanoke.

-

There are also candidates for lieutenant governor and attorney general.

How will the Republican nominee be chosen? Can I vote?

In short: in an unassembled convention, and…it’s complicated.

When it comes to elections, most of the drama involves the candidates. But among Virginia Republicans, there was also plenty of drama around how to even choose their nominees for statewide races. It took weeks of debate and infighting for state party leaders to settle on an unassembled convention instead of a primary (like Democrats are holding) or party-run canvass.

And even then, their initial choice to hold the convention as a drive-thru at a Liberty University parking lot (to comply with COVID-19 gathering restrictions) came undone within a day. The party ultimately settled on holding the convention at 39 sites across the commonwealth.

As for who can vote, the convention isn’t open to all comers, even if they are Republicans. Instead, just over 53,000 Republican delegates registered to participate. That’s significantly more than the 2013 convention where some 8,000 delegates took part, but far less than the Republican primary in 2017 that drew more than 365,000 votes for governor alone.

Republicans also briefly refused to make accommodations for Orthodox Jewish voters who can’t vote on the sabbath, before reversing that decision under pressure from national Republicans.

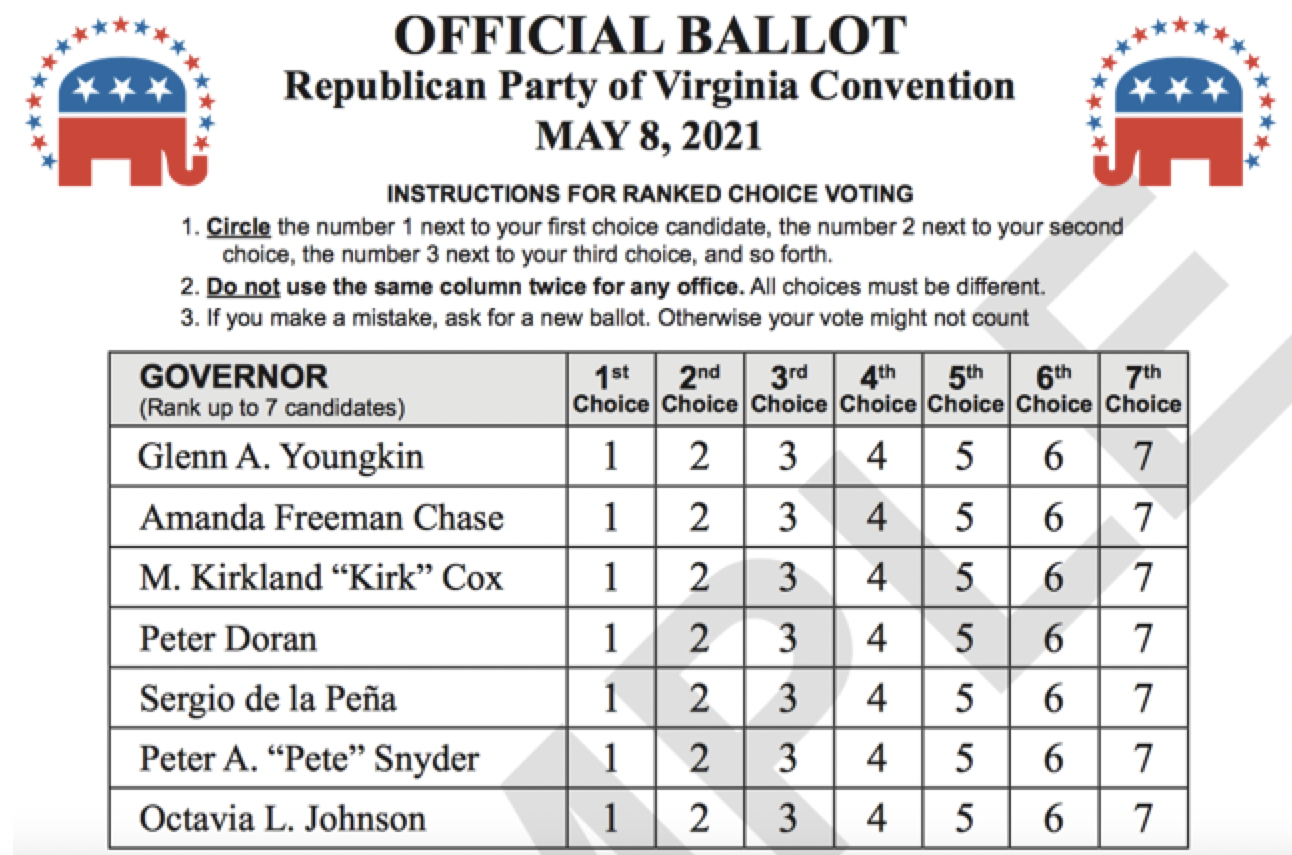

What’s this I hear about ranked-choice voting?

Beyond opting for an unassembled convention, party leaders also opted for a novel way of casting ballots: ranked-choice voting.

Under a ranked-choice voting system, each voter ranks all of the candidates in their order of preference. If no candidate hits the 50% mark on the first round of voting, the lowest-ranked candidate gets dropped and their votes are re-allocated to a person’s second-choice candidate. This process continues until a single candidate emerges with a majority of votes from delegates.

Ranked-choice voting is a favorite of some (usually left-leaning) advocates, who say it prevents large fields of candidates from splitting the vote and leaving the winner with less than a majority of votes. It also lets voters choose who they really like instead of holding their nose for someone they think can win. (It also makes being someone’s second choice a potentially big deal.) Republican leaders said it would also allow delegates to cast a single ballot and leave, instead of having to stay in a single location for multiple rounds of balloting.

Along with the convention, the option to use ranked-choice voting rubbed some of the candidates the wrong way. Chase, the pro-Trump state senator who is a favorite among the party’s base, has claimed that the way Republicans will select their nominee was chosen to thwart her; she could have won a plurality in a traditional primary, the thinking goes.

On top of all this, ballots are being weighted so that delegates from certain parts of Virginia with traditionally high Republican turnout will have more voting power. All of the means that tallying the votes — which will start on Sunday, May 9 — could take a few days.

What are some of the issues in the Republican gubernatorial race?

Most of the candidates have focused in on the defining reality of the last year: the coronavirus pandemic. Specifically, they have criticized Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam for his restrictions on businesses and his pace of reopening schools, which they have pledged to speed up. The candidates have also taken aim at Democrats’ control in Richmond — a popular refrain is that Virginia is becoming the new California — and new gun restrictions that have been passed since last year. (That includes one-gun-a-month purchase limits, red flag laws, universal background checks, and local power to impose new limits on where guns can be carried.)

The candidates have also focused on policing and criminal justice, saying they would oppose any moves to defund the police. And they’ve criticized the Virginia Parole Board, which has come under fire for some of its decisions. Some, meanwhile, have made sweeping promises — Doran says he’d eliminate the commonwealth’s income tax and build hyperloops in specific parts of Virginia, for example. Others, like Cox and Chase, have highlighted their legislative work as proof that they can get things done in Richmond.

But being that this is a battle between Republicans, there have also been plenty of red-meat issues for the base tossed out there. Candidates have criticized “cancel culture,” critical race theory, and Big Tech. They’ve put an emphasis on “election integrity,” shorthand for laws that could restrict voting that have come in the wake of former President Donald Trump’s false and baseless claims that the 2020 election was rigged. (Many of the candidates have pledged to follow the lead of Georgia and other states that are passing sweeping new voting restrictions.)

A few of the candidates have presented themselves as Trump-style contenders, and have sought to link themselves to the former president. Chase has referred to herself as “Trump in heels,” and even flew down to Florida to try and get his endorsement. Youngkin has used his personal wealth to flood the airwaves with ads tying himself to Trump, while Snyder has touted endorsements from former Trump press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders and Ken Cuccinelli, a former Trump official who ran unsuccessfully for governor in Virginia.

All of this is happening against an interesting backdrop: Trump lost Virginia to President Joe Biden by 11 points, the biggest such drubbing since the 1988 presidential election.

What are the GOP’s chances to win the gubernatorial race?

Saturday’s convention is only step one of the process; after that, the Republican nominee will go head to head with whomever wins the Democratic primary next month. (There’s also a third-party candidate, Princess Blanding.) And that fight is expected to be an uphill climb, if only because of Virginia’s recent political history. The GOP hasn’t won statewide since 2009; it votes steadily Democratic in presidential elections now; Democrats took the General Assembly in 2019; and recent polling found that while most Virginians define themselves as moderate-leaning-conservative, they also support many Democratic positions on health care, immigration, the environment, and taxes.

It is true that Virginia has tended to go in the opposite direction as Washington; with Democrats in control there and in Richmond, Virginia Republicans think they can draw stark contrasts between themselves and the governing party.

Still, for Republicans to win statewide, they’ll need to make inroads into Northern Virginia again, the commonwealth’s most populated area — and one full of active and informed voters. This was actually the topic of discussion at a debate hosted by the Fairfax GOP last month, when de la Peña observed: “If you want to win, you’ve got to win in Northern Virginia. The demographics have changed. We’ve got 20% of Hispanics in Northern Virginia, another 16-17% of Asians. We’ve got to reach out to those communities if we’re going to win.”

Republicans say they may be able to use the school reopening debate to win back some Democratic and independent voters, but some political analysts say they doubt it will be enough given how polarized and intense national politics has gotten. Also, given that Republicans chose a convention, those analysts say that the candidates have had to cater to the party’s base — which could alienate them from other voters.

“[The convention] will only be attended by the hardcore base. And in order to win that, the candidates are catering to issues that will not work in the general elections and therefore being pro-Trump, being anti-immigration, being critical of the school systems, being critical of the COVID-19 protections and measures that the governor has taken,” said David Ramadan, a former Republican delegate from Northern Virginia.

“All of these are issues that the average voter cares about and puts the Republicans at odds with that electorate and therefore unlikely to be able to win any statewide elections any time soon.”

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle